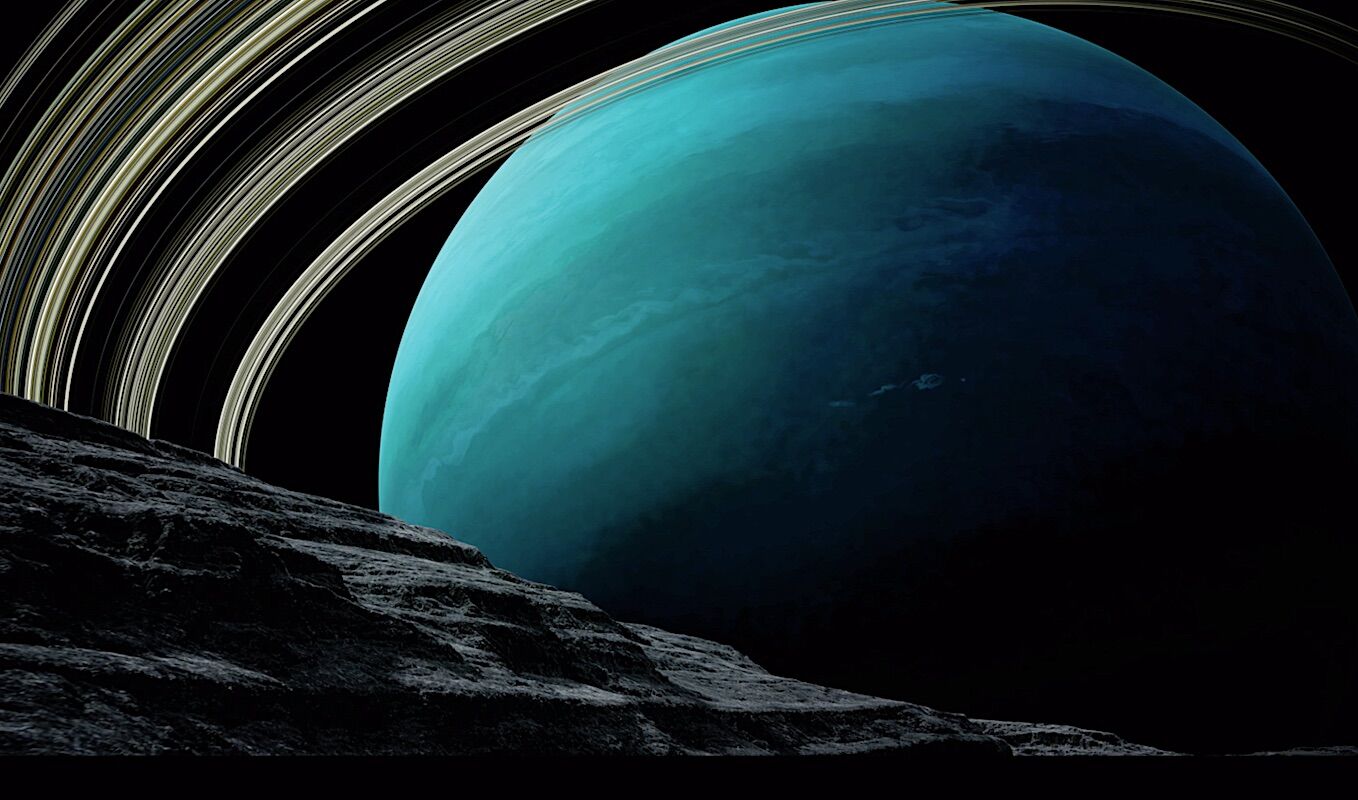

NASA SVS

“If we had arrived a week earlier, we would have had a completely different image of Uranus”

Uranus’s ion radiation belt is not as faint as Voyager 2’s first observations suggested. How does the ice giant’s system manage to keep so much radiation trapped?

The two “ice giants” of the Solar System, Uranus and Neptunecontinue to be the least explored planets of all those orbiting our Sun.

Due to huge distance that separates us from them, the first probe to study them up close was the Voyager 2which remains the only mission to perform a simple flyby of these worlds.

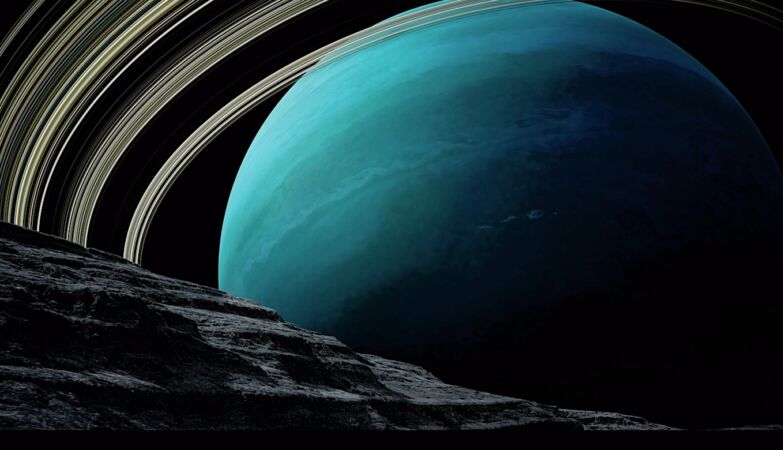

What the iconic probe revealed gave rise to countless riddles about both planets, their moon systems and other characteristics. When it passed by Uranus, for example, Voyager recorded a very intense electron beltwith energy levels much higher than expected.

Since then, scientists have studied thousands of gas giants beyond the Solar System and made comparisons that only increased the mystery: how the Uranus system manages keep so much electron radiation trapped?

In a recent publication in the magazine Geophysical Research Lettersresearchers from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) put forward the hypothesis that the results of Voyager 2 observations may have been caused by a solar wind structure.

Similar to what happens on Earth, where processes driven by solar wind storms have profound effects on the magnetosphere, the team suggests that a “co-rotating interaction region” would have been traversing the system when Voyager 2 performed its historic flyby.

The investigation was led by Robert C Allenspace physicist and principal scientist in the Space Sciences Division at SwRI. The main scientist also participated in the work Sarah Vines and the senior program manager George C. Ho.

To date, the Voyager 2 probe has provided the only direct measurements of the radiation environment around Uranus. From these data, the widely accepted view was constructed that there would be a relatively weak ion radiation belt and an extremely intense electron radiation belt.

However, when reanalyzing the probe’s records, the team found evidence that the observations were not made under “normal” solar wind conditions. Instead, the authors suggest that the flyby coincided with the passage of a transient solar wind event through the system.

This event will have produced the more intense high frequency waves observed throughout the Voyager 2 mission, say the study authors, in a SwRI.

At the time, scientists thought that these waves would scatter the electronswhich would eventually be lost in the atmosphere of Uranus. However, space research has shown that, under certain circumstances, the same waves can also accelerate electrons and inject additional energyplanetary systems.

It was with this in mind that the team compared Voyager 2’s observations with similar events recorded on Earth – and found clear parallels.

“Science has advanced a lot since the Voyager 2 flyby. We decided to take a comparative approach, looking at the Voyager 2 data and comparing it with observations of Earth we have made in the decades since,” Allen says in the SwRI statement.

“In 2019, Earth experienced one of these eventswhich caused an immense acceleration of electrons in the radiation belts,” adds Sarah Vines. “If a similar mechanism has interacted with the Uranus systemthat would explain why Voyager 2 detected all this unexpected additional energy.”

The comparative approach used in the study suggests that interactions between the solar wind and Uranus’ magnetosphere may have generated high frequency waves capable of accelerating electrons to energies corresponding to speeds close to that of light.

The work also raises several additional questions about the fundamental physics behind these intense waves and the sequence of events that gave rise to them.

“AND one more reason to send a mission specifically dedicated to Uranus. The findings have important implications for similar systems, such as Neptune,” concludes Allen.