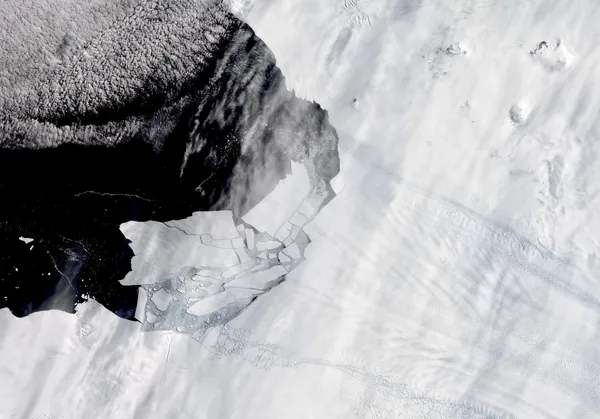

And with that there will be a rise in sea levels – a worrying rise

According to a recent study, underwater “storms” are aggressively melting the ice shelves of two vital Antarctic glaciers, with potential “far-reaching implications” for global sea level rise.

Antarctica is like a fist with a skinny thumb toward South America. The Pine Island Glacier lies near the base of this thumb. Thwaites – known as the Doomsday Glacier, due to the devastating impact its disappearance would have on global sea level rise – is located next to it.

Over the past few decades, these icy giants have undergone rapid melting, driven by warming ocean water, especially where they rise from the sea floor and float like ice shelves.

The new study, published last month in the journal Nature Geosciences, is the first to systematically analyze how the ocean is melting ice shelves over hours and days, rather than seasons or years, its authors say.

“We are observing the ocean on very short, weather-like timescales, which is unusual in Antarctic studies,” says Yoshihiro Nakayama, study author and assistant professor of engineering at Dartmouth College.

The underwater storms in which they concentrated – called “submesoscales” – are rapidly changing ocean eddies.

“Think of them as little whirlpools of water that spin very quickly, like when you stir water in a glass,” says study author Mattia Poinelli, an Earth system science researcher at the University of California, Irvine, and a NASA affiliated researcher. However, in the ocean, these eddies are not small – they can reach almost 10 kilometers.

They form when hot water and cold water meet. Returning to the cup analogy, it’s the same principle as when you pour milk into a cup of coffee and you see little whirlpools spinning, mixing everything.

The phenomenon is similar to the way thunderstorms form in the atmosphere – when hot air and cold air collide – and, like atmospheric storms, can be very dangerous.

Whirlpools swirl in the open ocean and run beneath ice shelves. Placed between the ice shelf’s complex, rugged base and the sea floor, the eddies stir up warmer water from deep in the ocean, which increases melting when it “hits” the vulnerable ice, Nakayama says.

Scientists used computer models as well as real data from ocean instruments to analyze the impact of these underwater storms.

They found that, along with other short-lived processes, the storms caused 20% of the melting of the two glaciers over a nine-month period. “Quantifying the exact contribution of storms alone is challenging due to their chaotic nature,” says Poinelli, but these events appear to play an important role over short periods of time.

The researchers also highlighted a worrying feedback loop. As storms melt the ice, they increase the amount of fresh, cold water entering the ocean. This mixes with the warmer, saltier water beneath, generating more ocean turbulence, which in turn increases ice melting.

“This positive feedback loop may gain intensity in a warmer climate,” says study author Lia Siegelman of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

The consequences can be serious, as ice shelves play a vital role in containing glaciers, slowing their flow into the ocean. The Thwaites Glacier alone contains enough water to raise sea levels by more than 60 centimeters. But because it also acts as a cork holding back the vast Antarctic ice sheet, its collapse could lead to a rise in sea levels of around 3 meters.

The study is important “because it sheds light on the role of small ocean features in melting the base of ice shelves,” says Tiago Dotto, a senior researcher at the UK’s National Oceanography Center who was not involved in the study. The extent of ice melting found in the study was “surprising”, Tiago Dotto told CNN.

The uncertainties are still enormous. Antarctica’s ice shelves are some of the least accessible places on Earth, which means scientists have to rely heavily on simulations. “These types of studies are intriguing, but they are computer models,” says David Holland, professor of mathematics and atmospheric and oceanic sciences at NYU, who was also not involved in the study. Much more real-world data is needed to truly understand the impact of these eddies, as well as other ocean weather conditions, David Holland tells CNN.

There are also many factors that contribute to the melting of ice on this vast continent. “Hundreds of things have similar importance to ice sheet decomposition,” says Ted Scambos, a senior researcher at the Center for Earth and Observational Sciences at the University of Colorado in Boulder, who was not involved in the study. “Awareness of the dynamics of the ocean near the ice sheet is evolving rapidly,” he tells CNN.

The study clearly shows that more data is needed to understand how underwater storms can vary across seasons and years. However, these short-term climate processes are “far from negligible”, underlines Poinelli.

“Studying these small-scale ocean phenomena is the next frontier in ocean-ice interactions that help us understand ice loss and, ultimately, sea level rise,” says Siegelman.