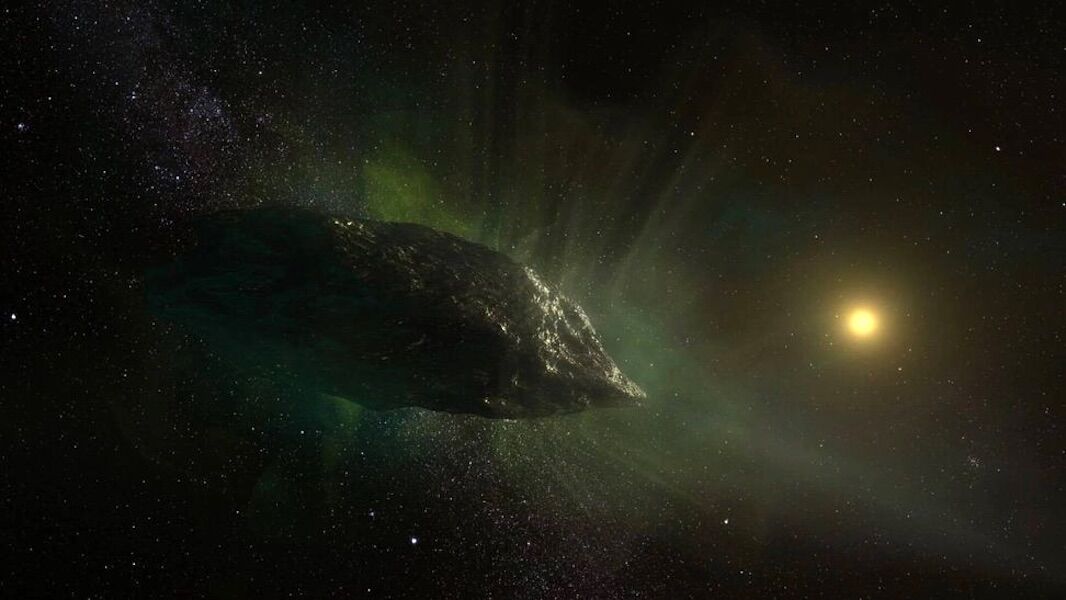

S. Dagnello / NRAO / AUI / NSF

Illustration of an interstellar object, such as ‘Oumuamua or 3I/ATLAS, passing through the solar system

The European Space Agency’s Comet Interceptor mission aims to travel to one of the next interstellar objects that cross the Solar System. A recent study analyzes the difficulties of this mission.

In recent months, there has been much speculation about the nature of the interstellar object, largely due to the faint data quality that we can obtain by observing it from Earth or Mars. In any case, it is much further than would be ideal for detailed analysis.

However, this may change soon. The European Space Agency, ESA, is planning a mission, the (CI), to approach the next interstellar object or a comet that is on its way to the interior of the Solar System.

Given the limitations of the mission, any potential target would have to meet a set of conditions.

In a new, recently pre-published in arXiv, Colin Snodgrassan astronomer at the University of Edinburgh, and his colleagues, analyze what these conditions are, and evaluate the probability of finding a good candidate within a reasonable time after mission launch.

The Comet Interceptor is a F class mission of ESA, which means it was designed to be developed and launched quicklyexplains .

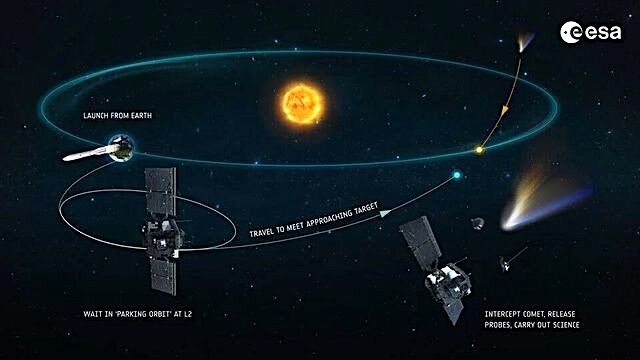

After launch, the ESA probe will remain in a waiting orbit at the point of Lagrange L2 of the Earth–Sun system, until a suitable target emerges: a Dynamically New Comet (DNC)a type of comet that, like 3I/ATLAS, would be entering the interior of the Solar System for the first time.

ESA

Graphic representation of ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission

If the mission is successful, you can observe an interstellar object as it passes through our Solar System on its passage path, although the probability of this happening within a reasonable distanceat the exact moment the CI is on hold, be shockingly low.

However, NCDs are more common. The article identifies 132 of these comets between 1898 and 2023, although each has its own particularities. Many are extremely faint and are only discovered a few months or years before reaching the interior of the Solar System.

This is where another mission comes ino: The Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) mission is expected to discover many more DNC than have ever been observed and, with luck, give enough time to the IC team to analyze a potential target and determine its suitability.

But even if LSST finds a reasonable candidate, there is no guarantee that the comet increases in brightness to a truly interesting level as it approaches the Sun.

Also there is no guarantee that it will not disintegrate before the IC could get close enough to inspect it. Since the mission can only choose a single target, These unknowns introduce a degree of randomness Big enough to make you think twice.

Therefore, it is preferable to explore possible scenarios using , to get a clearer idea of what to expect when selecting a real target.

This analysis began with some basic mission restrictions. Firstly, there is a limited delta-v — the energy needed to reach the comet — imposed by the limitations of the ship that has to transport the fuel to L2. The authors estimate this value at 1.5 km/swhich is not particularly high by the standards of interplanetary missions.

About CI would have to intercept the comet somewhere between 0.9 and 1.2 AUroughly in the vicinity of Earth’s orbital path — and, crucially, it has to cross the ecliptic plane where the Earth actually isto stay within reach.

Furthermore, the ship also must keep the Sun at an angle between 45° and 135°to ensure the operation of the solar panels. And, perhaps most importantly, the comet flybycannot occur at more than 70 km/sbecause the damage caused by the dust could destroy the small probes that the IC would release to study the comet’s coma.

Added to this is the existence of a optimum degassing point: the target comet must produce enough gas to be interestingbut not so much that it destroys the probe. According to the study authors, Halley’s Comet appears to be a reasonable upper limit for the required outgassing.

A probability of finding an ideal candidate in the 2-3 year window of the CI mission is not very high. Therefore, operators will likely have to settle for a “good enough” target and collect what data they can.

This is an inherent limitation of this type of missions, in which the final target is only known after the mission was designed and launched. Still, with any luck, the CI could find a good candidate, most likely with the help of LSST, when it launches in 2029.

Perhaps, with great luck, even find an interstellar visitor who you can cross paths with; If that happens, we might actually watch the famous “” that Arthur C. Clarke prophesied in 1937.