Iberian Peninsula

According to a new study, the ground beneath the Iberian Peninsula is, and always has been, moving in a slow but measurable clockwise rotation.

The Iberian Peninsula, the huge block of Europe where Portugal and our neighbor Spain are located, is not the static landmass we imagine: is running clockwise at a pace too small to be felt by people, but significant enough to change the way scientists understand the world. seismic cliff in southwestern Europe and North Africa.

This slight rotation of the peninsula is due to the colossal and chaotic collision between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates.

In the area where these plates meet, the crust does not behave like a single, “clean” boundary. Instead, it bends, absorbing tension in some places and transferring it to others — twisting, in the process, all of Iberia.

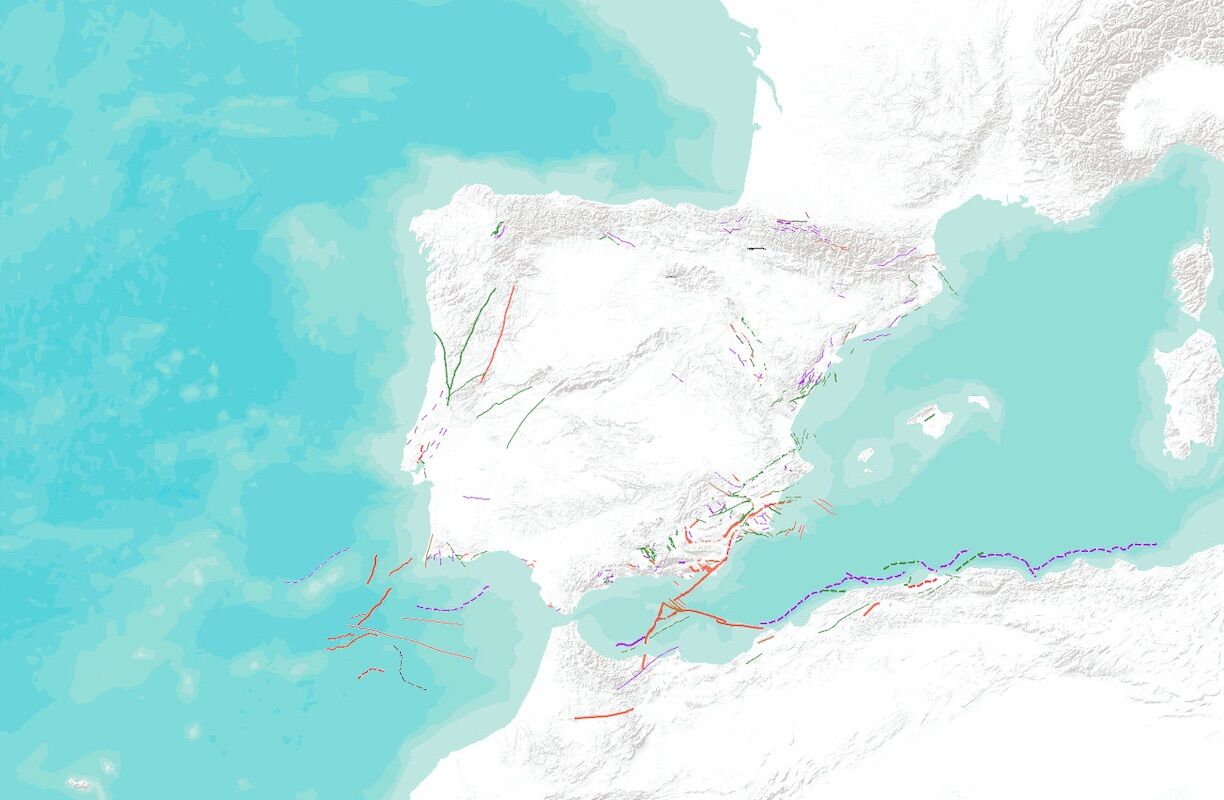

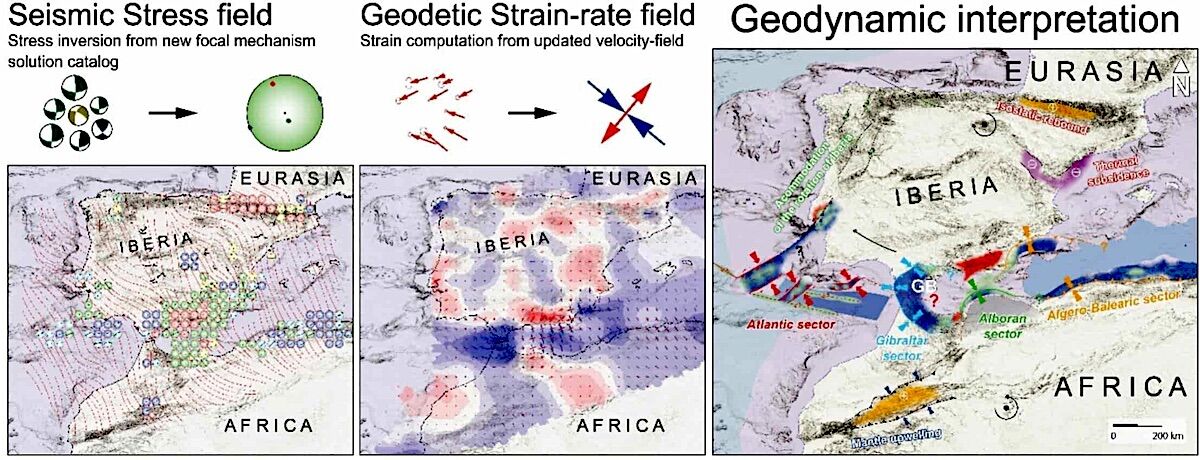

The displacement was measured and mapped in detail thanks to a , published in the January 2026 issue of the magazine Gondwana Researchwhich combines two distinct ways of “seeing” the Earth’s movement: the small jolts of earthquakes and the almost imperceptible drift detected by satellites.

Geology textbooks often show tectonic plates meeting along sharp, well-defined lines. This works for mid-ocean ridges or deep subduction zones. To the south of the Iberian Peninsula, however, reality is more complicated.

Africa and Eurasia converge at a rate of about 4 to 6 millimeters per year — approximately speed at which nails grow. In the Atlantic Ocean and along the Algerian coast, the boundary between the plates is relatively clear.

But near the south of Spain and the north of Morocco, it dissolves into a wide area of interacting blocksfolded mountain belts and hidden faults.

Gondwana Research

At the center of this dynamic is the subsoil of the Alboran Seaa fragment of Earth’s crust beneath the western Mediterranean. This block glide west and helps shape the arched mountain range known as the Arc of Gibraltar, which connects the Betic Mountains in Spain to the Rif mountainsin Morocco.

Until now, this “blurred border” has made it difficult to determine precisely how tension actually moves across the region, explains .

The Gibraltar Complication

The new study, led by Asier Madarietaa geologist at the University of the Basque Country, faces the problem combiningo two large data sets.

One comes from earthquake records — in particular, the geometry of movement on faults during seismic events, which reveals the directions of stress at depth. The other comes from hundreds of GPS stationswhich follow the way in which the Earth’s surface shifts in fractions of a millimeter per year.

Taken together, these data show that the plate boundary behaves very differently on each side of the Strait of Gibraltar.

East of the strait, the crust of the Gibraltar Arc acts as a shock absorber: absorbs much of the tension produced by the Africa–Eurasia collision. West of the strait, this buffer fades. There, Iberia collides directly with Africa.

“East of the Strait of Gibraltar, the crust of the Gibraltar Arc is absorbing the deformation caused by the Eurasia–Africa collision,” explains Madarieta. “On the other hand, west of the Strait of Gibraltar, the direct collision between the Iberian (Eurasian) and African plates.”

It’s this uneven pressure which gives the Iberian Peninsula its slow rotation.

Satellite data confirms it: southern and southwestern Iberia move differently than the north. The peninsula is thus deforming and rotating clockwise, pushed from below and sideways by an asymmetrical collision.

On a human scale, this move seems irrelevant. But on the scale of earthquakes, the imperceptible rotation matters – a lot.

The same stress fields that drive Iberia’s rotation also determine where faults get “stuck” and where they slide. In some areas of the peninsula there is clear deformation or frequent seismicity, but the faults responsible remain invisible at the surface.

“There are many places where there is significant deformation or where earthquakes occur, but We don’t know what tectonic structures are active there”, notes Madarieta. “These stress and deformation fields tell us where we have to go looking for these structures.”

This guidance is crucial in regions such as southwest Iberiawhere the seismic risk is real, but poorly mapped.

The most striking example of this risk happened in 1755when the large earthquake off Lisbon, estimated at magnitude 8.7, devastated the city and generated tsunamis that crossed the Atlantic.

Since then, smaller but still damaging earthquakes have occurred, scattered along a border that refuses to behave in a “neat” way. You new maps help to refine this search.

By identifying where stress is being transferred rather than absorbed, the study guides researchers to hidden faults that could generate earthquakes in the future.

Still, researchers are keen to do not exaggerate the range of the conclusions. Modern seismic records go back only a few decades, and high-resolution satellite measurements only began around 1999.

“These data give us just a small window about geological evolution”, says Madarieta. Plate tectonics unfolds over millions of years. What scientists observe now It’s a snapshot, a fleeting glimpse of a much longer history.

Despite this, it is the clearest glimpse to date. And though the ground may seem firm beneath our feet, is, and always has been, in motion.