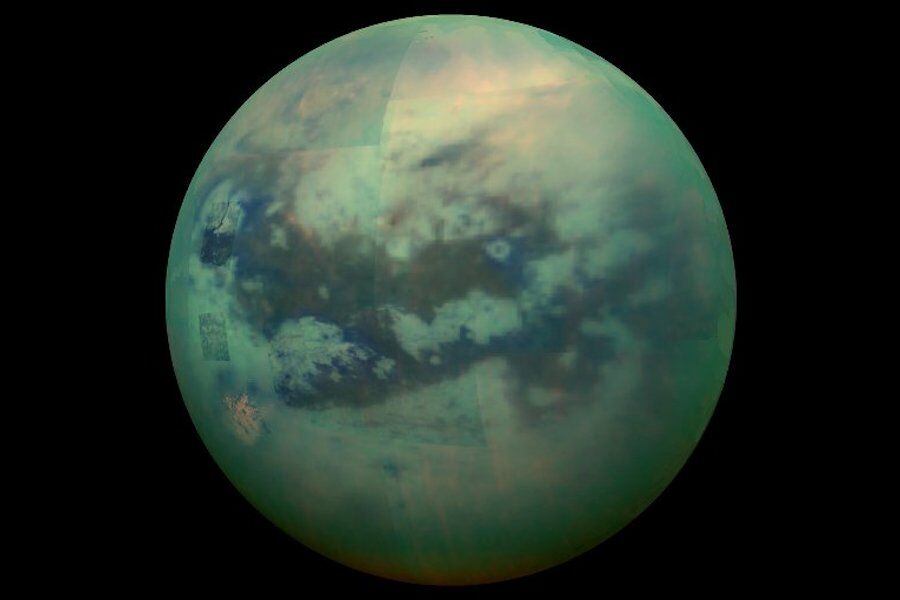

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon.

NASA wrong 20 years ago? There is no ocean, but rather an immense layer of “pasty” ice that increases the possibility of life on Saturn’s largest moon, new research indicates.

A new reanalysis of data collected by NASA’s Cassini mission suggests that Titanthe largest moon in Saturnmay be less “oceanic” than previously thought — but not necessarily less promising in the search for life beyond Earth.

The study, led by NASA scientists and researchers at the University of Washington, points to a thicker and more viscous interior, with a “muddy” layer beneath the icy crust rather than a vast global ocean of liquid water, which could increase the likelihood that habitable niches for simple life forms exist.

Titan is one of the main targets for astrobiology in the Solar System. Among Saturn’s 274 known moons, it stands out for being the only body, other than Earth, where there can be stable liquids on the surfacealthough not water, points out .

On Titan, rivers, lakes and rain are mainly composed of hydrocarbons, such as methane and ethane. With surface temperatures in the order of –179 °Cthese environments are considered unlikely to support life as we know it.

Despite this, since 2008, Cassini data has fueled the hypothesis of a large underground ocean of liquid water, protected under an ice crust. The possibility of an “internal sea” opened space for speculation about extraterrestrial ecosystems and even the viability of more complex life forms in extreme conditions.

In recent years, the idea of oceans hidden under ice has gained strength on other moons, such as Europa and Ganymede (from Jupiter) and even Mimas (from Saturn): future missions, say the most optimistic, could find some robust evidence of life beyond Earth.

The new research focused on a crucial detail: how Titan deforms — and when it does so — in response to Saturn’s gravity.

The gravitational “tide”, as happens with ocean tides on Earth, causes the celestial body to stretch. The amplitude of this deformation, and above all the delay with which it occurs, allows us to infer properties of the interior.

The deformations observed in previous analyzes were compatible with a global ocean, but depended on the moon’s internal architecture: a deep ocean would allow the crust to flex more; a fully frozen interior would limit this flexing. What has changed now is the explicit incorporation of “time” in the modeling.

A closer review of the Cassini records indicates that Titan’s maximum deformation occurs about 15 hours later of the peak gravitational force exerted by Saturn. By including this delay, the team concluded that the energy dissipated inside Titan is much greater than previously estimated. This suggests an internal material that is thicker and more viscous than liquid water, requiring more energy to deform.

“Nobody was expecting such a strong dissipation of energy inside Titan,” he says Flavio Petriccapostdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and leader of the study, describing the result as a “decisive indication” that the interior is different from the classic scenario of an open ocean.

Instead, the proposed framework is closer to Arctic sea ice or aquifers: a “muddy” and brackish sub-surface layer, possibly with pockets of water.

And this is where the story gains new interest for astrobiology. A global ocean tends to disperse nutrients; small pockets or localized reservoirs can, on the contrary, concentrate them, creating microenvironments where chemistry favorable to life occurs more intensely. This local enrichment, the authors argue, could facilitate the emergence and maintenance of simple organisms — similar to those that inhabit polar and subglacial environments on Earth.

The updated model also admits that, under specific conditions influenced by Saturn’s gravity, brine transitional zones relatively “hot”, reaching around 20 °C in highly localized areas. Episodes like this, even temporary, would increase the window of habitability and expand the range of environments considered potentially alive, with implications also for the way we think about habitability on other worlds.

For future missions, NASA is preparing , a drone that is expected to explore Titan in 2028. The new study suggests that the mission will not find a scenario of complex life “swimming” in pasty channels. But, if there are signs of life, they could correspond to simple forms, adapted to extreme niches, and Titan could continue to be one of the best natural laboratories to understand how far life can go.