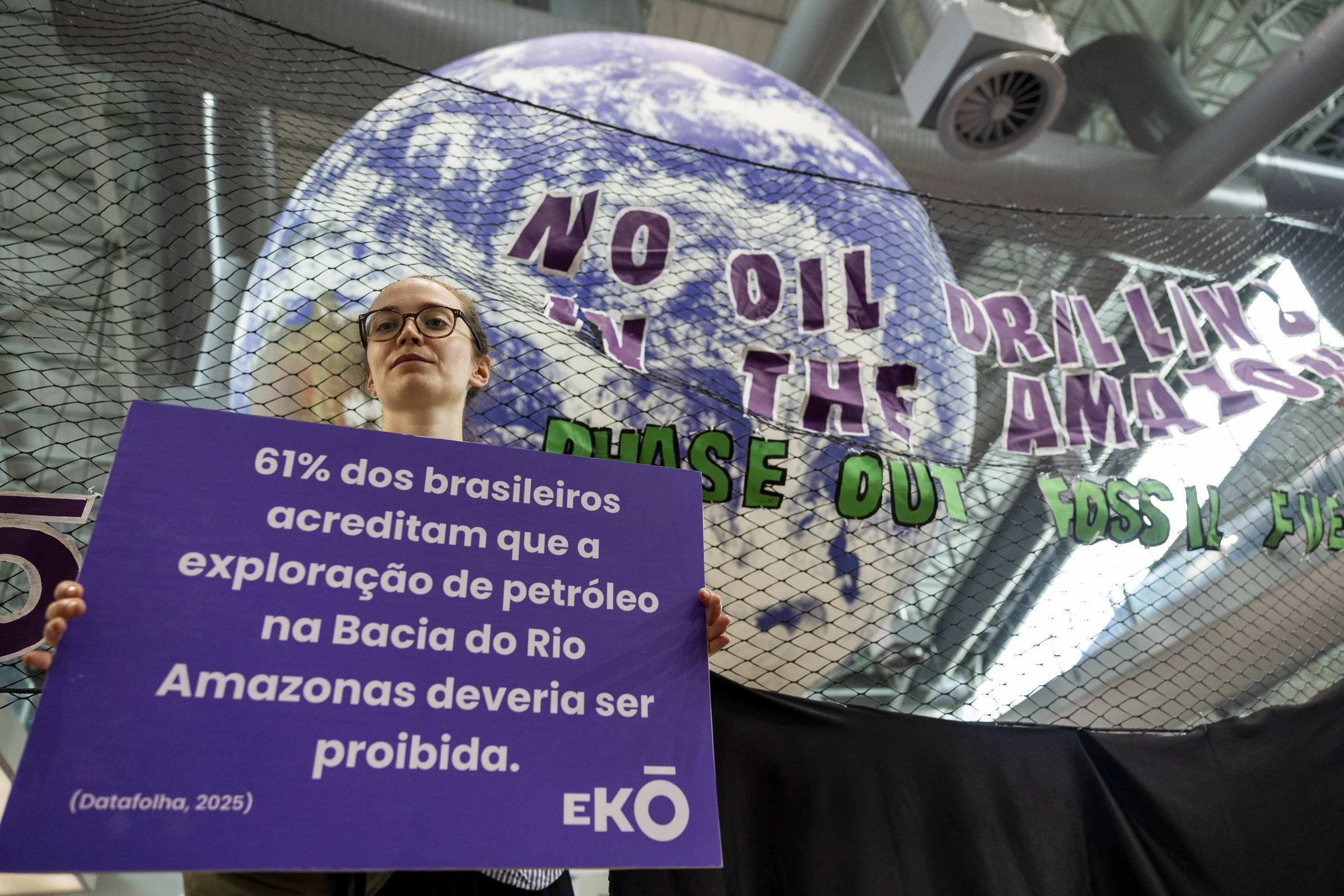

With the work of , in Belém, concluded, all analyzes coincide in pointing out the coordinated effort of oil-producing countries — notably Saudi Arabia and Russia — to veto any global initiative aimed at . The success of this strategy was clear: the term “fossil fuels” did not even appear at the meeting.

There is no doubt that this represented a defeat in the fight against global warming. The question I intend to discuss is whether this “defeat” really corresponds to a victory for the oil and gas sector in the long term.

When searching for the answer, I remembered the article by Theodore Levitt —a mandatory read by GV in the 1970s—, and my own experience in the banking sector.

Around 1910, says Levitt, a Boston millionaire — a loving father, but probably unconvinced of his children’s financial abilities — determined that his entire fortune would remain invested in shares of electric streetcar companies, condemning his heirs to poverty. Levitt uses this anecdote to support his thesis: companies do not fail due to the obsolescence of their products, but because they poorly define the market in which they operate, focusing on what they produce, not on the needs of their customers. This happened with the American railroads, which saw themselves in the “train business”, not in the transportation business.

The idea is simple but powerful. Throughout my banking career —largely focused on serving large companies—, I have always tried to focus on being close to customers and understanding their needs, letting products emerge as a response, not as a starting point. When demands changed, so did the solutions.

In my final years as an executive, now also responsible for retail, I encountered the difficulty of applying Levitt’s teachings when this required profound changes. For established companies (incumbents), distinguishing between the real threat and the passing fad takes time. An innovation does not emerge or assert itself as a superior solution overnight: it needs to go through a period of testing, learning, mistrust and losses.

The delay, often seen in the reaction, is not just a result of the natural aversion that we all have to change —”Lusitana is the one who likes change”, said a friend—, but mainly from the feeling of comfort offered by the belief in the so-called “entry barriers”, existing in all areas of business… until they cease to exist.

For railway companies in 1900, the tracks laid between the main cities seemed like an insurmountable barrier. After all, who would build a new railway on an already served route?

The equivalent of rails in retail banking was the branch network. For decades, expansion took place through the opening of units: a large network made it possible to serve a larger audience, achieve scale and offer products at a competitive cost. For a new entrant, it would be almost impossible to compete without acquiring an existing bank.

Until not.

which reach a significant portion of customers —especially younger ones— without the need for agencies, at a much lower cost and offering service that delights their audience, have emerged. At that initial moment, there were still doubts regarding the viability of the model. Could they become profitable? Would they know how to deal with the complexity of credit? Could they evolve beyond single-product platforms and offer a broad range of services?

The temptation to simply wait and see is great, but that would be a serious mistake. Regardless of the success that the new competitors achieved, the undeniable fact was the emergence of a form of service that met the expectations of many customers. This was enough to justify the commitment to incorporating new learning and adapting the business model.

I remember a phrase I read at the time: “Incumbents need to find innovation before innovators find the market.”

Finding innovation is not just about offering a new product. It is about promoting internal transformation: evolving systems, reviewing the role of agencies, changing the way work is organized and, ultimately, the company’s own culture. An arduous and long process, which requires leaders to have the humility to place themselves as apprentices.

Fortunately, in , the bank where I worked — on whose board I now sit — intensified the transformation, improving its services and achieving a noticeable improvement in customer satisfaction indicators — the result of combining the virtues of the traditional and digital models. More relevant than the results is the leadership’s clarity that much remains to be done and that the challenges of evolution are permanent.

My intention in reporting this experience is to draw a parallel between the challenges faced by railways in 1900, traditional banks in the last 15 years and those facing the energy sector today.

The enormous cost reduction of , the new —cheaper — forms of storage and the exponential expansion of the supply of these sources place the fossil sector facing the same dilemma. Believing that they rely on their oil reserves as a barrier to entry, many leaders do not realize that their business is not oil, but energy.

Answering the initial question, I would say that the “victory” of postponing the transition represents, in the long term, a defeat for the fossil sector itself. By resisting the changes that are already shaping the future of energy, its leaders only slow down the transformation process on which its relevance will depend.

The decision to start today whose oil will only reach the market in 12 or 15 years corresponds, in my opinion, to the choice of a bank to expand its branch network in the midst of the digital revolution (I wouldn’t invest in that bank!). COP30 showed that external pressure can be contained; What cannot be contained is the changing needs of “customers” — countries, companies and societies that already demand cheaper, cleaner and safer energy. It is in this market, not in additional barrels, that the future lies.

LINK PRESENT: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click the blue F below.