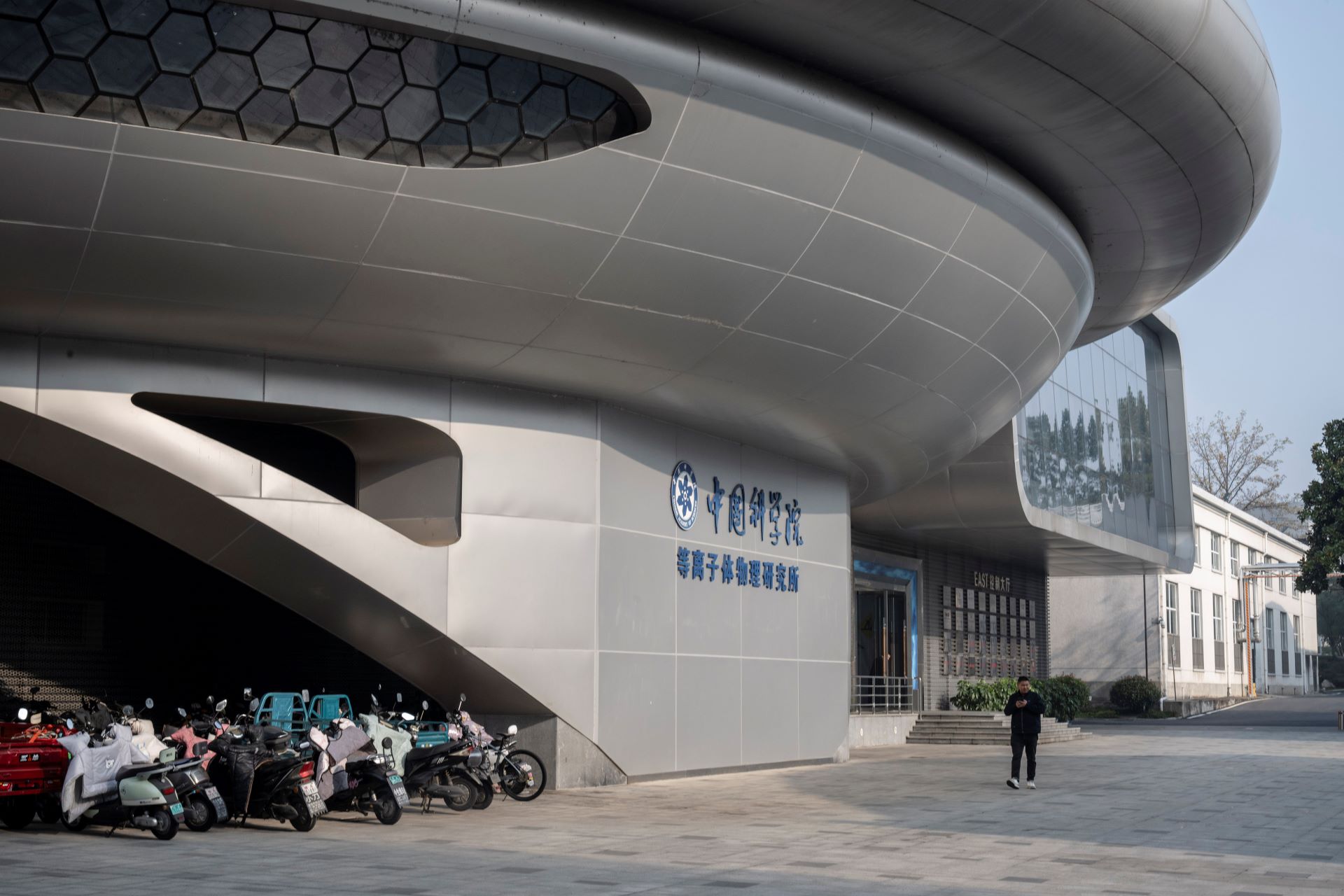

HEFEI, China — On a leafy campus in eastern China, crews are working day and night to complete a massive circular structure with two arms the length of aircraft carriers.

In ancient rice fields in the southwest of the country, a huge X-shaped building is being built with equal urgency and under great secrecy. The existence of this facility only became widely known after researchers identified it in satellite images about a year ago.

Together, these colossal projects represent China’s most ambitious efforts to master an energy source that could transform civilization: nuclear fusion.

Continues after advertising

Fusion, the union of atoms to release extraordinary energy, uses abundant fuels, presents no risk of melting and does not generate long-lasting radioactive waste. It promises almost unlimited energy, capable not only of meeting the growing demand for electricity to power artificial intelligence, but also of ending dependence on fossil fuels that are dangerously warming the planet.

A century ago, scientists began to imagine fusion, the energy of stars. In recent decades, much progress has been made to reproduce the process in the laboratory using magnets and lasers. But forcing unruly atoms to come together is much more difficult than splitting them, as occurs in the fission that generates the current one.

A fusion reactor must first heat hydrogen to temperatures higher than those of the sun, transforming it into plasma, the fourth state of matter. Then, it must keep this violent plasma confined long enough for the atoms to fuse and release energy. China, the United States and other countries are racing to develop machines capable of performing this feat repeatedly, with the reliability to power an electrical grid.

The two global superpowers are fiercely competing for dominance over the energy future. Under the Trump administration, the US has focused on producing oil, gas and coal for export. Its main economic rival, China, has become a world leader in clean energy, supplying solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles.

The merger could be a game changer for both of them and the world. Whoever masters it will be able to build plants globally and form new alliances with energy-hungry countries. But Americans and Chinese have very different strategies for getting there.

The USA bets on private initiative and American innovation, with occasional government support. From coast to coast, startups accelerate their search with urgency and creativity.

Continues after advertising

On the other side of the world, the Chinese government has made the merger a national priority, mobilizing resources at an impressive pace. Recently, a Shanghai startup matched a breakthrough by Commonwealth Fusion Systems, the best-funded fusion company in the US, in much less time. Over the summer, the Chinese government and private investors pumped $2.1 billion into a new state-owned fusion company — 2.5 times the U.S. Department of Energy’s annual fusion budget.

The two countries’ progress may soon be tested.

The Commonwealth says that by 2027, its experimental device in Massachusetts will produce more energy than it consumes — a milestone that would indicate that fusion could generate electricity for data centers, steel mills and others.

Continues after advertising

China’s leading plasma physics laboratory hopes its new machine, called BEST, installed in the twin-arm building in the east of the country, will achieve this goal in the coming years.

“It’s a tight schedule,” said Lian Hui, a scientist at the laboratory. Still, “we are very confident that we will achieve BEST’s research objectives,” he said.

A national priority

China’s commitment to science and fusion comes from the highest levels.

Continues after advertising

The government’s new five-year plan, for 2026-2030, promises “extraordinary measures” to ensure progress in fusion and other areas. The Chinese state-owned nuclear company is preparing detailed proposals for fusion research, calling it “the main race track in the scientific and technological competition between great powers”.

Two decades ago, China was a small fish in the merger and grew by collaborating with other countries. — a donut-shaped fusion machine. He became a key collaborator in the ITER experiment, involving 33 nations. Over the past decade, American and Chinese researchers have carried out joint experiments and extolled the “long-term friendship” between the countries in plasma physics.

Now, Chinese laboratories and companies build cutting-edge facilities of their own. The Institute of Plasma Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences builds the BEST tokamak and a 40-hectare complex to develop and test components that withstand the extreme conditions of fusion. Scientists also project another tokamak for a pilot plant in the 2030s or 2040s.

Continues after advertising

Richard Pitts, a British-French physicist at ITER, visited the BEST site in January last year, when it was just an empty platform. Today, it’s half done.

China has learned a lot from ITER and is now applying that knowledge to move forward, Pitts said. “Every time I go there, I am amazed at the number of people and the efficiency with which things are done.”

Even if the core technology works, fusion reactors will only power the world when companies can build and operate them economically and on an industrial scale.

At this point, China’s expertise in engineering and construction gives it the edge, said Jimmy Goodrich, a researcher at the University of California. “The risk for the US is creating the viable technical path first, but China being the one to scale and implement it first.”

Recently, the Commonwealth got a taste of Chinese speed.

Last year, the company’s scientists published papers about its large D-shaped magnets for the tokamak in Massachusetts, made from materials that conduct electricity with very low resistance, generating super-strong magnetic fields.

In the summer, a Shanghai startup, Energy Singularity, published an article about a very similar magnet.

For Dennis Whyte, co-founder of Commonwealth, this wasn’t just reverse engineering. Mobilizing supply chains and expertise to manufacture and test a magnet this quickly showed “impressive skill.”

The laser path

In the southwest, another front of Chinese fusion is advancing with less fanfare.

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Engineering Physics, in Sichuan, closely followed the work of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California, which in 2022 achieved a promising demonstration: lasers made a piece of hydrogen “light up”, producing more energy than it consumed.

A senior Chinese academic scientist soon urged the country to follow suit.

Livermore’s feat was “a great scientific achievement that will go down in history,” said Zheng Wanguo in an interview in early 2023. China should “strengthen investment and research” in fusion, “with laser ignition as the main technical approach.”

Within a year and a half, a huge X-shaped facility appeared near Mianyang.

Reports from the Chinese laser industry, scientific articles and patent application indicate that the site will house Shenguang IV, a new laser ignition facility. Proposals for this facility, whose name means “Divine Light,” have existed for more than 15 years, but Livermore’s success accelerated the project.

The speed of construction at Mianyang is “breathtaking,” said Kimberly Budil, director of the Livermore lab, which took 20 years to build its facility. Still, “operating the system reliably requires skills that China will have to learn,” he said.

Scientists at the Chinese Academy of Engineering Physics keep it secret because, like many at Livermore, they work on nuclear weapons research. Laser fusion makes it possible to study nuclear explosions without detonating real weapons.

With the rapid growth of China’s nuclear arsenal under Xi Jinping, the Army is looking for ways to maintain it, experts say.

In recent months, the academy announced plans for another laser ignition facility in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan — a smaller, more commercial version of the one in Mianyang.

And Peng Xianjue, once an anonymous weapons designer, turned energy entrepreneur, promoting an experimental reactor that would combine fusion and fission. In this year’s proposal, Peng argues that China “targets commercial application by 2040”.

Collaborate or separate

The US-China divide in the merger caught the attention of Alain Bécoulet, a French physicist, when he was in Chengdu in October for the International Atomic Energy Agency conference. There were no Americans, he said.

The U.S. Department of Energy under Trump discouraged American scientists from participating, three researchers reported to The New York Times. The department did not comment.

“Today China is innovative,” said Bécoulet, chief scientist at ITER. “You’re not just copying.”

China’s Institute of Plasma Physics announced in November that it welcomes partnerships with foreign scientists for its BEST tokamak. “The door is always open,” said Dong Shaohua, responsible for international collaborations.

But with energy security increasingly vital to industries like artificial intelligence, many in American government and industry see the merger as a decisive battleground for global influence.

“Whoever wins and dominates sets the foundation for the century,” said Ylli Bajraktari, head of the Special Competitive Studies Project, a research organization in Washington.

In October, the US Department of Energy released a new plan to help the fusion industry grow and commercialize in the 2030s. The document calls for construction and modernization of several scientific facilities, but abandoned the previous initiative to lead the design of a pilot plant by the 2040s.

According to the department, American startups are already moving quickly to build this plant.

For some scientists, the US government needs to do more.

Investors have already invested around US$14 billion in merger companies around the world, including US$7.6 billion for American firms. “It’s a lot of money, but it’s going to take a lot more to cross the finish line,” said George Tynan, a plasma scientist at MIT.

Chang Liu worked for years as a physicist at the US Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. It recently tried to recruit young scientists, but the lab cited a lack of budget, he said. Experiences like this, combined with family reasons, led him to move to Peking University, one of the best in China. A Princeton spokesperson said the lab does not comment on personnel matters.

In the US, a lack of government support is one of the reasons so many researchers flock to startups, Liu said.

On the other hand, Chinese authorities are investing heavily in a possible “definitive solution” for humanity’s energy needs, he said. “They really invest in what’s important.”

c.2025 The New York Times Company