In a discovery of great importance for astrophysics and observational cosmology, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently revealed the explosion of a single massive star — a supernova — in a galaxy observed at a time when the Universe was only about 650 million years old.

The finding surprised astronomers in March 2025, as it has precise pointing, which focuses on specific targets for long periods. Therefore, encountering a supernova in the “infancy” of the Universe can be considered a matter of luck, when the telescope’s attention was diverted to something that exploded.

Typically, Webb “sees” in infrared to peer through dust and capture light from very distant objects, which reaches us redshifted due to the expansion of space. In other words, the main focus of the space telescope is to detect the faint and continuous light from primitive galaxies.

In this context, gamma ray bursts (GRBs) are fundamental, as they function as ephemeral beacons. Although extremely powerful, these flashes are short-lived, but their light passes through the cosmos and illuminates distant galaxies, allowing JWST to study the chemical composition of the first stars before their wake disappears.

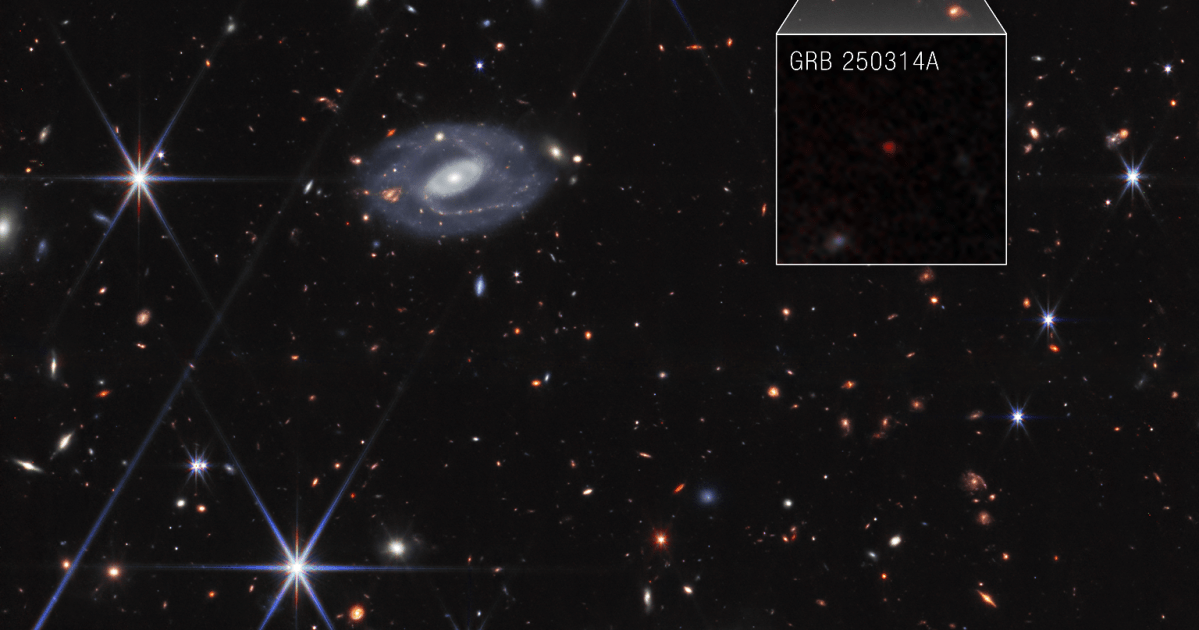

According to the study, GRB 250314A was the central element that allowed the discovery of the ancestral supernova. As soon as they realized that this event was coming from a record distance, the authors used an observation program of opportunity to redirect JWST to the region of the sky where the GRB’s afterglow could still be detected.

Analyzing cosmic explosions to reveal dead stars

In the context of astrophysics, transient events — such as GRB 250314A — are astronomical phenomena that appear suddenly, shine brightly for a short period (from seconds to months), and then disappear or drastically decrease in intensity.

Unlike a galaxy, which Webb can observe today, tomorrow or ten years from now, a transient event demands haste, because it is a unique opportunity. That is, if astronomers don’t point the telescope quickly (as they did with GRB 250314A), the light goes out and the information is lost forever.

Finding a supernova from the Era of Reionization is like winning the lottery, as it is a period in which the first stars and galaxies began to illuminate a Universe that was still very young, and to dissipate the neutral hydrogen fog that existed before. Therefore, these objects appear very pale and difficult to detect.

In a press release, the study’s lead author, Andrew Levan of Radboud University in Nîmegen, Netherlands, highlights the space telescope’s capabilities. “This observation also demonstrates that we can use Webb to find individual stars when the Universe was just 5% of its current age.”

In this context, the fact worked as an “alarm”, which alerted scientists about where to look. And, when they observed, they realized that the “baby” stars of the Universe behaved in the same way as the dying stars in our cosmic neighborhood today.

Did stars die at the beginning of the Universe the same way they die today?

Despite the cosmic transformations that have occurred since the event, Webb revealed that the ancestral supernova surprisingly resembles modern ones. During the Era of Reionization, . Because the gas between the galaxies was opaque, high-energy light could not pass through it easily.

According to co-author Nial Tanvir, professor at the University of Leicester, in the United Kingdom, “we went in with an open mind”, that is, we expected to find something very different in the behavior of stars that existed around 13 billion years ago, formed almost exclusively by hydrogen and helium.

Therefore, the great scientific surprise of the article was the realization that that supernova with redshift z ≃ 7.3 did not change significantly, even with the passage of billions of years and the change in the chemical composition of the Universe. However, the authors highlight, although they look the same, data is based on a few pixels of the JWST image.

The current success has earned the team a little more observation time at Webb. The goal now is to capture the infrared afterglow of GRBs as a chemical “fingerprint.” The idea is to investigate the properties of primitive galaxies, transforming each ephemeral explosion into a kind of probe into the past.

To confirm that the observed brightness is indeed that of a supernova, the researchers plan to carry out follow-up observations in 2026. Final confirmation will only come when they can compare the photo of the explosion with a photo of the “empty” location — just with the galaxy —, ensuring that they did not confuse its brightness with that of the dead star.