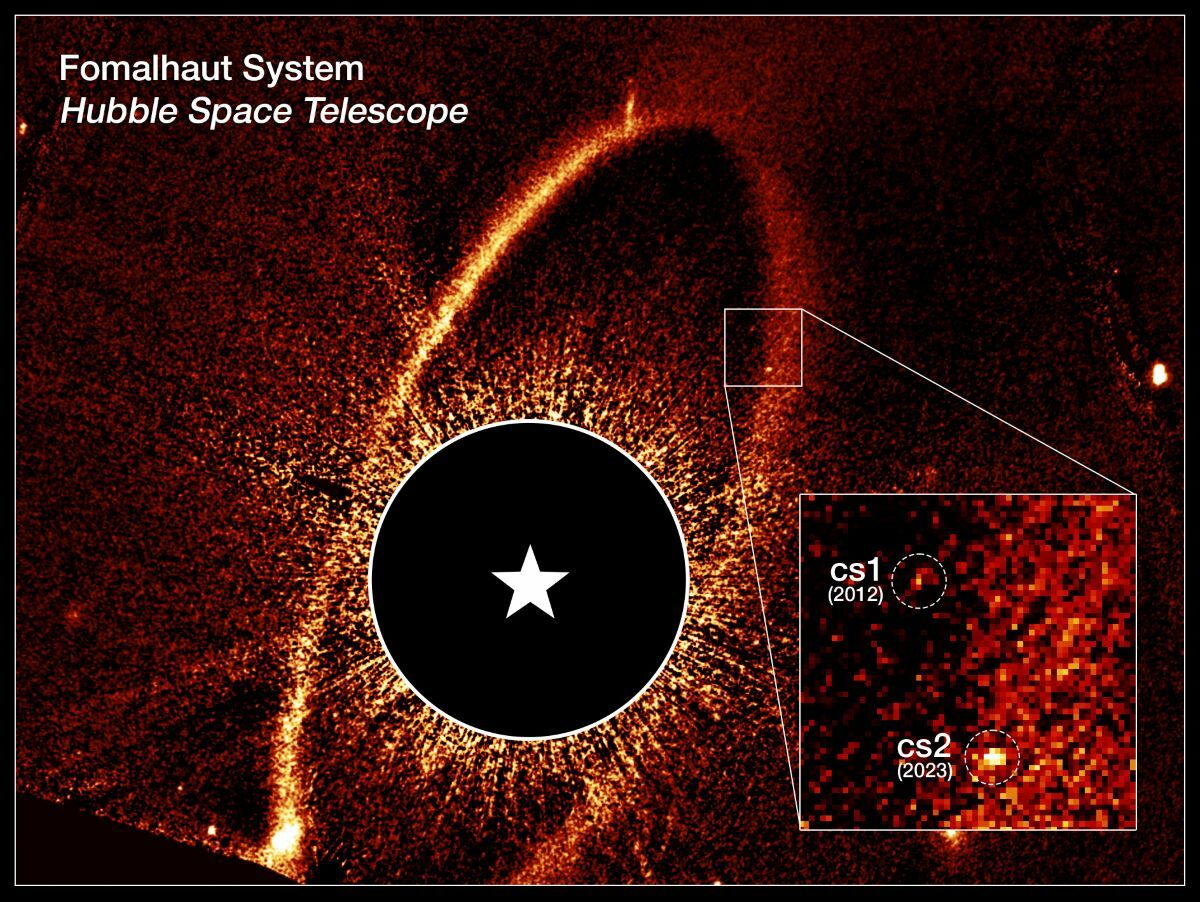

NASA, ESA, Paul Kalas (University of California at Berkeley); image processing – Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

This composite image, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, shows the debris ring and dust clouds cs1 and cs2 around the star Fomalhaut. Fomalhaut herself is masked to allow the faintest features to be seen. Its location is marked by the white star.

Scientists initially believed that the star Fomalhaut might have a planet in its rotation, but the object was just a cloud of dust.

Like cosmic bumper cars, scientists think the early days of our Solar System were a time of violent disorderwith planetesimals, asteroids and comets colliding with each other and bombarding the Earth, the Moon and the other inner planets with debris.

Now, in a historic milestone, the Hubble Space Telescope has directly captured images of catastrophic collisions similar ones in a nearby planetary system around another star, Fomalhaut.

“This is certainly the first time I have seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system,” said principal investigator Paul Kalas of the University of California at Berkeley. “It is absent from all previous Hubble images, which means we have just witnessed a violent collision between two massive objects and a huge cloud of debris, unlike anything currently in our Solar System. Amazing!”

Just 25 light years from Earth, Fomalhaut is one of the brightest stars in the sky nocturnal. Located in the constellation Peixe Austral, it is more massive and brighter than the Sun and is surrounded by several belts of dusty debris.

In 2008, scientists used Hubble to discover a planet candidate around Fomalhaut, making it the first star system with a possible planet found using visible light. This object, called Fomalhaut b, now appears to be a dust cloud disguised as a planet – the result of the collision of planetesimals. While searching for Fomalhaut b in recent Hubble observations, scientists were surprised to find a second point of light in a similar location around the star. They call this object “circumstellar source 2” or “cs2”, while the first object is now known as “cs1”.

Solving the mysteries of planetesimal collisions

Why astronomers are seeing these two debris clouds so close together is a mystery. If collisions between asteroids and planetesimals were random, cs1 and cs2 should appear by chance in unrelated locations. However, they are positioned intriguingly close to each other along the inner portion of Fomalhaut’s outer debris disk.

Another mystery is why scientists witnessed these two events in such a short period of time. “Previous theory suggested that there should be a collision every 100,000 years or so. Here, in 20 years, we have seen two“, Kalas explained. “If we had a movie of the last 3000 years and we sped it up so that each year was a fraction of a second, imagine how many flashes we would see over that time. The Fomalhaut planetary system would be shining with these collisions.”

Collisions are fundamental to the evolution of planetary systems, but they are rare and difficult to study.

“The exciting aspect of this observation is that it allows researchers to estimate the size of the colliding bodies and how many of them are in the disk, information that is almost impossible to obtain by any other means“, said co-author Mark Wyatt of the University of Cambridge in England. “Our estimates place the planetesimals that were destroyed to create cs1 and cs2 at just 60 kilometers in diameter, and we infer that there are 300 million such objects orbiting in the Fomalhaut system.”

“The system is a natural laboratory for probing how planetesimals behave when they collide, which in turn tells us what they are made of and how they formed,” explained Wyatt.

Lesson of caution

The transient nature of Fomalhaut cs1 and cs2 poses challenges to future space missions that aim to directly image exoplanets. These telescopes can confusing dust clouds like cs1 and cs2 with real planets.

“Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an exoplanet that reflects starlight,” Kalas said. “What we learned from the study of cs1 is that a large dust cloud can masquerade as a planet for many years. This is a cautionary tale for future missions looking to detect exoplanets in reflected light.”

Looking to the future

Kalas and his team were given Hubble time to monitor cs2 over the next three years. Do you want to see how it evolves – does it fade or get brighter? Being closer to the dust belt than cs1, the expanding cs2 cloud is more likely to start encountering other material in the belt. This could lead to a sudden avalanche of more dust into the system, which could cause the entire surrounding area to become brighter.

“Let’s follow cs2 to detect any changes in its shape, brightness and orbit over time,” said Kalas, “It is possible that cs2 will begin to take on a more oval or cometary shape as dust grains are pushed outward by the pressure of starlight.”

The team will also use the NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to observe cs2. Webb’s NIRCam has the ability to provide color information which can reveal the size of the cloud’s dust grains and their composition. It can even determine whether the cloud contains water ice.

Hubble and Webb are the only observatories capable of obtaining these types of images. While Hubble sees mainly in visible wavelengths, Webb can see cs2 in the infrared. These different and complementary wavelengths are needed to provide a broad investigation multispectral and a more complete picture of the mysterious Fomalhaut system and its rapid evolution.

This was published in the December 18th issue of Science magazine.