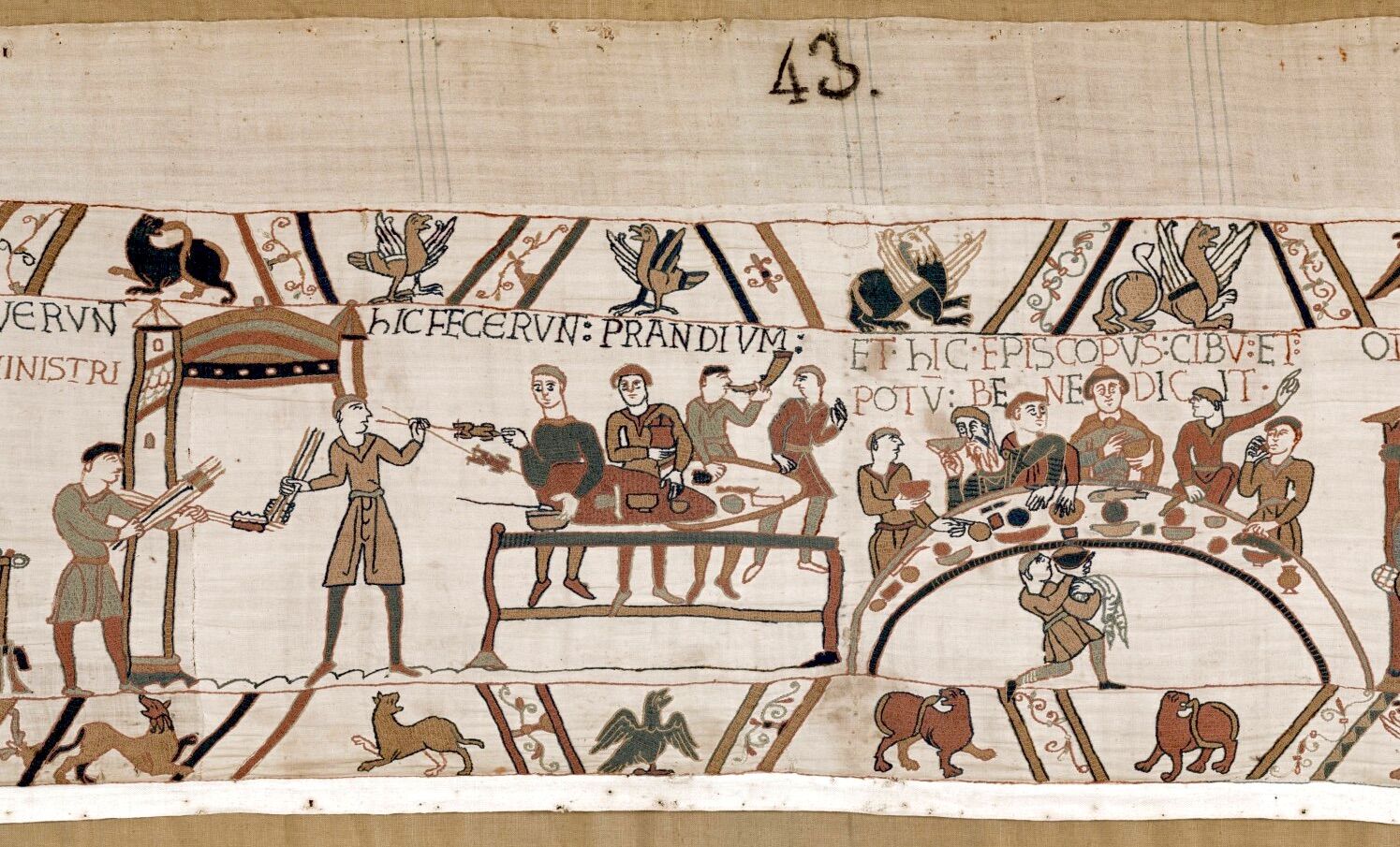

Bayeux Tapestry Scene 43

The Bayeux Tapestry, a huge embroidered cloth depicting the events leading up to the Battle of Hastings in 1066, has long been a mystery. But this once-forgotten work may have finally found its place.

Although it is practically consensual that it was designed by monks who lived in the Abbey of Saint Augustine, in Canterbury, England, and executed by a team of skilled embroiderers, we still don’t know for sure because it was created or where it was originally displayed.

In a new one, published at the beginning of the month in Historical Researchthe British historian Benjamin Pohl presents his theory.

Pohl believes that the tapestry served as a reading during meals for the monks of St. Augustine, or a similar place.

“I asked myself if a cafeteria context could help explain some of the seemingly inexplicable contradictions identified in existing research,” explains Pohl in one from the University of Bristol, referring to the communal dining rooms where monks shared meals.

“Just like now, in the Middle Ages, meals were always an important moment of conviviality, collective reflection, hospitality and entertainment, as well as celebrating community identity. In this context, the Bayeux Tapestry would have found the ideal setting”, maintains the historian.

Although there is no concrete proof that the Bayeux Tapestry was in Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Pohl highlights that there are several signs that suggest it may have been hanging on the walls of the abbey refectory.

With more than 68.4 meters long and approximately 350 kilos of weight, to impressive dimension of the tapestry (which you can view below in full), implies that, to be displayed, it would have to be mounted directly on a solid wall.

Full image of the Bayeux Tapestry (scroll to view)

Previously, researchers suggested that the tapestry may have always been in the Bayeux Cathedralwhere it was found, in the 15th century. However, Benjamin Pohl notes that the arcades and columns of the cathedral’s walls made it “one of the less suitable locations to display an embroidery of such gigantic size.”

Still, the tapestry was probably designed for a religious publicwrites Pohl, because “his overt, and perhaps deliberate, political ambiguityand the absence of partisanship, seem difficult to reconcile with the identity and self-image of the post-Conquest English aristocracy.”

Furthermore, the several inscriptions in Latinalthough simple, would require a degree of Uncommon literacy among the nobility from the 11th century. The monks, on the other hand, would have no difficulty interpreting the inscriptions on the tapestry, explains the .

A monastic public faz even more sense taking into account the strict rules that governed the monks during meals: they had to maintain absolute silence, even going so far as to use sign language to ask, for example, to pass the salt. Perhaps the tapestry functioned as moral and educational entertainment during meals.

“With the monastic community of Saint Augustine as its main recipient, the Bayeux Tapestry I didn’t need to tell stories of patriotism and national pride or resentment that modern commentators seek in it,” writes Pohl.

Instead, he suggests that the narrative can be read as “an account that revealed the God’s action through human deedssuch as episodes from the scriptures and other historical or hagiographic texts read during meals”.

The refectory of Saint Augustine would have been the ideal place to hang a work of art of such unusual dimensions: with at least 70 meters of interior wall, the building I had more than enough space for the tapestry – even though the final section, currently missing, extended several additional meters.

In the 1080s, a new cafeteria for the abbey, but a series of setbacks delayed its construction. First, there was the premature death, in 1087, of St Augustine’s first post-Conquest abbot, Scolland, who had driven the renewal.

Afterwards, the death of his unpopular successor, Wido, against whom the monks openly rebelled, left the position of abbot vacant for more than a decade. When the place was finally occupied by Hugo Ipriorities were different, which meant that the refectory was only completed in the 1120s.

Perhaps, in the midst of this long process of renewalo, Pohl suggests, the tapestry was stored and ended up being lost from the collective memory of the monastic community.

“Consequently, it may have been stored for more than one generation and forgotten, until it ended up in Bayeux three centuries later”, says Pohl.

This could explain how he survived several catastrophes that hit the abbey — a fire, an earthquake and a renovation in the 13th century — and also its absence in any records until it appeared in an inventory in Bayeux, in 1476.

“There is still no way to conclusively prove the whereabouts of the Bayeux Tapestry before 1476, and it may never exist,” explains Pohl. “But the evidence presented makes the monastic refectory of Saint Augustine a serious candidate”.