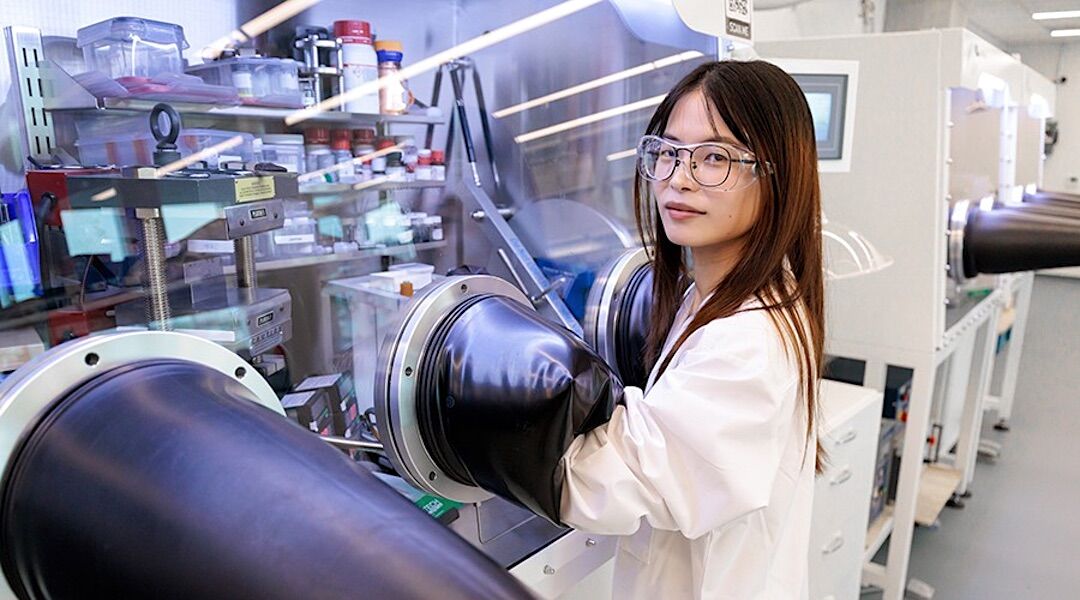

John Zich

Jing Wang, a researcher at the University of Chicago, is the first author of a study that revealed some of the main causes of – and ways to mitigate – the degradation of single-crystal lithium-ion batteries

A hidden cracking mechanism explains why new materials used in battery construction perform less than expected, leading to capacity degradation, shortened lifespan and, in some cases, fires. The solution could revolutionize the future of electric vehicles.

A team of researchers from the School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory in the USA, solved the mystery of the hidden failure that has led to capacity degradation, shortened lifespan and, in some cases, fires in electric vehicle batteries.

The new , presented in an article published in Nature Nanotechnology, reveals the underlying causes, and ways to mitigate them, of nanoscopic-scale stresses that can lead to cracking in single-crystal lithium-ion batteries, an increasingly popular battery type for electric vehicles and other technologies.

“The electrification of society needs everyone’s contribution”says the teacher Khalil Amineresearcher at U.Chicago and one of the corresponding authors of the article, at the university. “If people don’t trust that batteries are safe and long-lasting, they won’t choose them”.

Due to cracking problems Long associated with lithium-ion batteries that use nickel-rich polycrystalline materials (PC-NMC) in the cathodes, in recent years researchers have turned to nickel-rich layered oxides. single crystal nickel (SC-NMC).

But these have not always shown similar performanceor higher, than the older model.

The new study, led by Jing Wangdoctoral student at U.Chicago, revealed the underlying problem: assumptions made from polycrystalline cathodes were being incorrectly applied to single crystal materials.

“When people try to transition to single crystal cathodes, they have been following design principles similar to those of polycrystals,” explains Wang, currently a postdoctoral researcher working with U.Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory.

“Our study identifies that the main degradation mechanism of single crystal particles is different from that of polycrystals, which leads to different composition requirements”, details the researcher.

The study not only called into question the conventional designas well as the materials used, redefining the role of cobalt and manganese in mechanical failure of batteries.

“Not only are new design strategies needed; will also be necessary different materialsso that batteries with single crystal cathodes reach their full potential”, says Ying Shirley Meng professor at U.Chicago and director of the Energy Storage Research Alliance (ESRA) at Argonne, also corresponding author of the article.

A Fissure Mystery

As a polycrystalline cathode battery charges and discharges, the small primary particles, stacked in layers, swell and shrink.

This repeated expansion and contraction can widen the “grain boundaries” that separate polycrystals — similar to how freezing cycle and defrosting opens holes on city roads.

As “grain boundaries”, or “grain borders” of batteries are the microscopic interfaces between the crystals (grains) inside the electrodes, where the crystalline orientation changes. These boundaries influence the transport of ions and electrons, affecting performance, durability and energy storage capacity.

“Typically, there is an expansion or contraction of volume in the order of 5 to 10%“, explains Wang. “When an expansion or contraction exceeds elastic limitsthis leads to particle cracking.”

If the cracks become too wide, there may be a electrolyte infiltrationcausing undesirable side reactions and release of oxygen, which raises safety concerns, including the risk of thermal runaway.

But, without getting to these more dramatic scenarios, there is a more everyday effect: a capacity degradation: Over time, batteries lose performance and become less and less able to provide the same load that they delivered when they were new.

Because they are not made of many stacked crystals, the materials used in single-crystal cathodes do not initially have these grain boundaries. But still, they continued mysteriously degrading.

The new study showed that changing the materials used was not as simple as replacing one component with another. “Degradation in single crystal NMC cathodes is predominantly governed by a distinct mechanical failure mode”, he stated Tongchao Liuchemist at Argonne and another of the paper’s corresponding authors.

“By identifying this mechanism, hitherto undervalued, this work establishes a direct link between material composition and degradation pathwaysoffering a deeper understanding of the origins of decline performance in these materials”.

Researchers have found that cracking in single-crystal cathodes is mostly driven by reaction heterogeneity. The particles were react to different rhythms, generating tension — not between several crystals, as in polycrystalline designs, but within a single crystal.

Different solutions

In polycrystalline cathodes, the composition involves a delicate balance between nickel, manganese and cobalt. Cobalt actually contributes to cracking, but was necessary to mitigate a distinct problemknown to researchers as Li/Ni disorder.

By building and testing a nickel–cobalt (no manganese) battery and a nickel–manganese (no cobalt) battery, the team found that for single crystal cathodes, the behavior was the opposite.

O manganese proved to be more harmful from a mechanical point of view than cobalt, and cobalt ended up helping batteries last longer. Cobalt, however, is more expensive than nickel or manganese.

According to Jing Wang, the next step in transforming this laboratory innovation into a product that has practical application in the real world now involves finding less expensive materials that reproduce the good results associated with cobalt.

“Advances happen in cycles“, says Khalil Amine. “You solve one problem and move on to the next. The insights described in this collaborative article will help future researchers at Argonne, U.Chicago, and elsewhere create safer and more durable materials for tomorrow’s batteries.”