//Wedk / Wikipedia; Appendix Store Guvara / Depositphtos

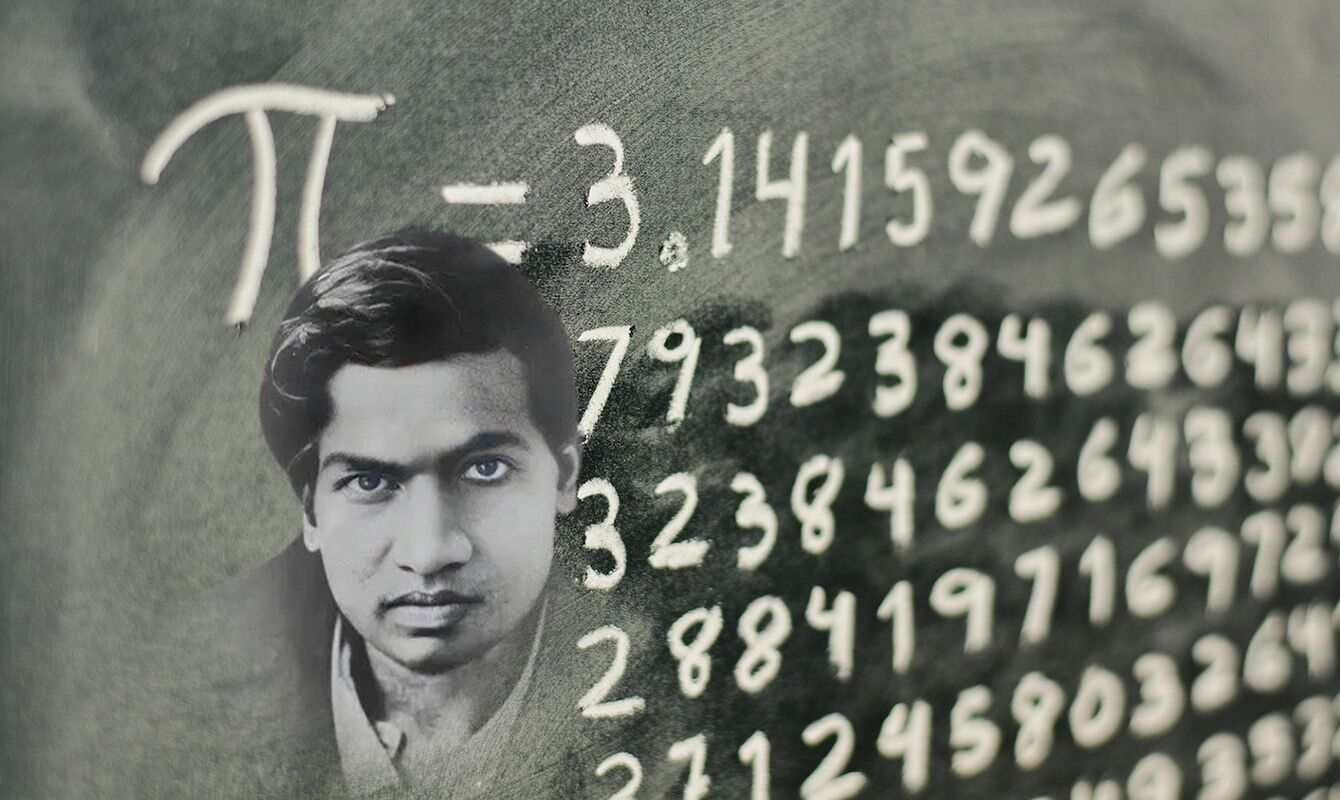

The renowned Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920), considered one of the greatest geniuses in mathematics

It is simply fascinating that a genius working in India at the beginning of the 20th century, with virtually no contact with modern physics, anticipated structures that are now central to our understanding of the universe.

In 1914, the renowned Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan published a brief article detailing several unusual formulas for calculating the value of number π. Using just a few mathematical terms, these formulas made it possible to generate many more digits of pi (π) than any existing method at the time.

Ramanujan’s work would later become central us algorithms modern calculations of pi. For physicists at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), however, these formulas raised a different question.

In a recently published Physical Review Lettersresearchers sought to understand why these compact expressions work so effectively. This question would eventually lead them to a unexpected destiny.

For decades, researchers mainly viewed Ramanujan’s formulas as tools for efficient calculations. Today, powerful computers can use similar methods to calculate pi with precision down to billions of digits.

“Scientists have already calculated pi up to 200 billion digitsusing an algorithm called Chudnovsky algorithm. These algorithms are, in fact, based on the work of Ramanujan”, explains Aninda Sinhaphysicist at IISc and lead author of the study, cited by .

Sinha and his collaborator, Faizan Bhatdecided to approach these formulas from a different perspective. Instead of limiting themselves to asking how they worked, they wanted to understand Why did formulas like this exist?.

“We wanted to understand if the starting point of his formulas fit naturally in some area of physics,” said Sinha. “That is, is there any physical world where Ramanujan’s mathematics arises by itself?”

Familiar pattern in unexpected contexts

The researchers They then turned to theoretical physicswhere certain mathematical patterns arise repeatedly in very different systems. In particular, they focused on a class of models known to mathematicians as “conformal field theories“.

These theories describe systems that have the same properties regardless of the scale at which they are observed. They are often found in critical points of physicswhere small changes can propagate to all scales at the same time.

For example, the water temperature and pressure can reach a critical point where liquid and vapor become indistinguishable. This phenomenon can also be observed in initial phases of turbulence of fluids. Some theoretical descriptions of black holes also resort to related formulas.

Within this broader category there is a group even more specialized: the calls logarithmic conformal field theories.

These models are mathematically complex, but they arise in many real physical contexts. In exploring these theories, researchers came across something surprisingly familiar.

Ramanujan’s logarithmic conformal field theories and pi formulas rely on close mathematical structures. This overlap allowed us to apply techniques inspired by Ramanujan to calculate certain quantities in these physical models.

Calculations that normally would require long and complex steps can thus be addressed more directly. This strategy echoes Ramanujan’s original approach, which extracted precise results from very compact expressions.

As Faizan Bhat explains, “in any branch of mathematics, we almost always find a physical system that reflects this same mathematics. Ramanujan’s motivation may have been purely mathematical, but without knowing it, he was also studying black holes, turbulence — a host of phenomena.”

The study does not suggest that Ramanujan anticipated practical applications of these concepts in modern physics. What it demonstrates is that mathematical ideas developed in an area may, over time, prove useful in another.

“We stayed simply fascinated with the fact that a genius working in India at the beginning of the 20th century, with virtually no contact with modern physics, anticipated structures that are now central to our understanding of the universe,” commented Sinha.

More than a century later, Ramanujan’s formulas continue to be rediscovered — not just as historical curiositiesbut also as tools for navigating complex concepts in contemporary physics.