A tiny bone lump of just five millimeters has reopened one of the fiercest debates in the history of paleoanthropology. A team from New York University has identified in the femur of Sahelanthropus tchadensis three anatomical characteristics that only appear in bipeds. This species may be the oldest known hominid, living seven million years ago in what is now Chad. The discovery would confirm that the most primitive ancestors of the human family already walked upright on two legs, an adaptation that until now had only been inferred indirectly from the position of the skull. And it also fuels a fierce scientific war that lasts more than 25 years between those who believe that the hominid could walk on two legs and those who not only categorically deny it, but also believe that it was not even a hominid.

“The femoral tubercle is unmistakable in hominids and is completely absent in chimpanzees,” explains the main author of the research published this Friday to this newspaper. That small lump, located at the top of the femur, is the insertion point of the iliofemoral ligament, the largest and most powerful in the human body, whose function is to prevent the torso from falling backwards when we stand or walk. “Their presence must have evolved shortly after our evolutionary divergence from chimpanzees,” adds Williams. Along with the tubercle, the team identified two other pieces of evidence, they say, that are unequivocal: a strong femoral antetorsion (the lower part of the bone is twisted inward, something that never occurs in apes) and a gluteal complex reorganized for upright walking.

The verdict comes after 25 years of scientific warfare to decide whether Sahelanthropus tchadensis Was it biped or not. The bones – a femur and two ulnae – were discovered next to a spectacular skull in the Djurab desert (Chad). They called him Toumaï, as they call babies born just before the dry season in that desert. It means “hope to live” in the local language. Its discoverers then assured that it belonged to a hominid with a brain similar in size to that of a chimpanzee, and that it was possibly bipedal, judging by the insertion place of the spinal column in its head.

But the limb bones remained cataloged as “remains of indeterminate fauna” until in 2004 a young student, Aude Bergeret, rediscovered them while searching the collections of the University of Poitiers (France). Bergeret and Italian paleontologist Roberto Macchiarelli analyzed the femur and came to an explosive conclusion: Sahelanthropus It moved on all fours and was probably not even a hominid, but an ape. They tried to publish their results for 16 years without success. Bergeret ended up being fired.

In 2020, Macchiarelli finally managed to publish his review in the magazine. Two years later, led by Michel Brunet, the French paleontologist who found Toumaï, he counterattacked with an analysis in Nature who defended exactly the opposite: Macchiarelli to his Poitiers colleagues of “omitting evidence”, “kidnapping material” and “lying about the origin of the femur”. Brunet responded that the delay was because his team was digging in Chad hoping to find more fossils, calling the accusations “a sad tale written by armchair paleoanthropologists.”

In 2024, Macchiarelli returned to the fray in a new study published in , arguing that the characteristics identified by Brunet in 2022 also appeared in carnivores, so they were not diagnostic of bipedalism. The debate seemed entrenched: two rival teams from the same university – Poitiers -, the same bones, irreconcilable conclusions.

Now, Williams and his team have done an independent analysis using 3D geometric morphometry, a technique that allows three-dimensional shapes to be measured with millimeter precision. “Science works best when independent researchers have the opportunity to provide fresh insight,” Williams explains. “In this case, that revealed the femoral tubercle and allowed us to independently examine features that were being debated by other teams.” The tubercle had gone unnoticed in previous analyses, probably because it is tiny and partially eroded, but Williams first identified it in a high-quality replica and then confirmed it in the original fossil.

But Macchiarelli categorically rejects the existence of the femoral tubercle. In a document sent to this newspaper, the Italian paleontologist attaches photographs of the original fossil taken by Aude Bergeret in 2004 and points out that the area where Williams identifies the tubercle is “highly damaged and incomplete, probably bitten by a carnivore and rudely cleaned with a mechanical cleaner.” Macchiarelli adds that the team responsible for the 2022 study itself recognized that “there is no evidence of the femoral tubercle” in the original fossil, and accuses Williams of having identified it only in replicas, “a highly limiting and risky analytical option.”

“The assumption magical trait represented by the femoral tubercle is extremely variable in humans and frequently present in modern great apes,” argues Macchiarelli. “The morphology [del fémur] and proportions, as well as numerous internal characteristics, are clearly similar to apes,” he concludes.

Salvador Moyà-Solà, emeritus researcher at the Catalan Institute of Paleontology, who has not participated in any of these investigations, agrees that the conclusion of the new study is hasty: “There are two basic problems: on the one hand, the material is fragmentary in anatomically very important parts, for example, the proximal and distal joints of the femur. On the other, the characters they cite are highly mediated by the incomplete state of the fossil and are minor characters” in the context of bipedalism. The Catalan scientist, a world leader in paleoanthropology and now retired, adds that “the similarities with the morphology and proportions of current African apes, gorillas and chimpanzees, are too important to be left aside.” In his opinion, “a certain degree of facultative bipedalism cannot be ruled out, but it did not have obvious anatomical adaptations to human bipedalism.”

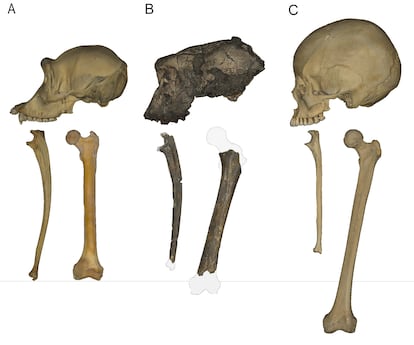

Williams stands by his conclusion. The result is paradoxical: Sahelanthropus He looks like a chimpanzee but walks like a human. “In their general surface appearance, the ulna and femur are most similar to chimpanzees,” Williams acknowledges, “but each bone presents one or more derived characteristics that resemble those of later hominids.” The strongly curved ulnae indicate that he continued to climb trees with agility. The proportions of the limbs are intermediate between bonobos and Australopithecus. But the three characteristics of the femur leave no room for doubt, according to the New York team: Sahelanthropus He walked upright.

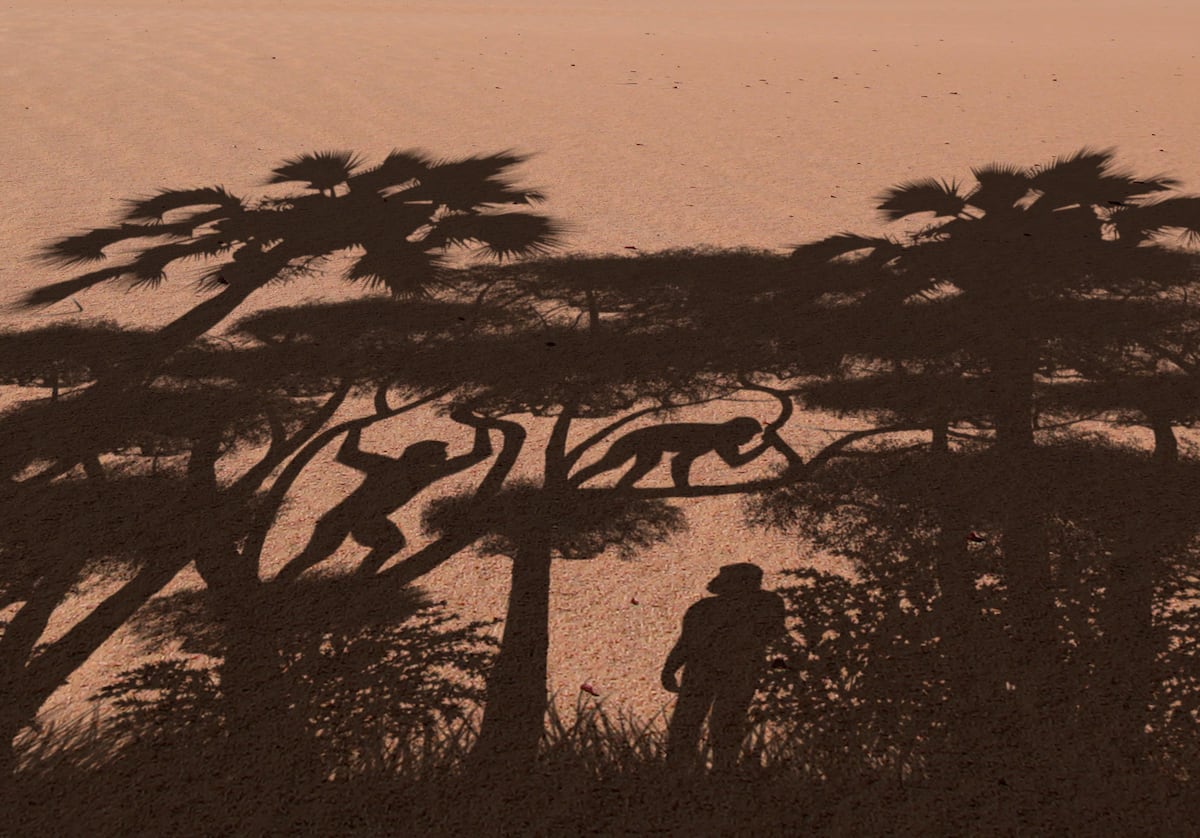

“I think that’s exactly what we’re seeing: a primarily chimpanzee- or bonobo-like ape that evolved bipedalism,” Williams explains. The image that emerges is that of a creature just over a meter tall and weighing 50 kilos that walked on two legs on the ground, but was still an expert tree climber. “Bipedalism appears to have evolved early in our lineage, but the dependence on climbing trees for food and security persisted for millions of years,” he adds.

The finding supports the hypothesis that the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees was more similar to a modern chimpanzee than to any extinct Miocene ape, as paleontologists of the stature of Tim White, discoverer of Lucy and Ardi, have defended. White, who now works at the National Center for Research on Human Evolution in Burgos, blessed the study by Brunet and his team in 2022: “Their conclusion is fully compatible with everything we know about early hominids: they were definitely neither like modern chimpanzees nor like modern humans, but they had already evolved in the direction of later hominids.”

Williams is cautious about whether his study definitively closes the debate. “I think our study adds more weight to one side of the argument. I am sure that the case is not closed: further work and future fossil finds could confirm or deny our findings,” he acknowledges. But he seems convinced: “My co-authors and I have become quite convinced that Sahelanthropus was bipedal” and that Macchiarelli and his colleagues “were probably wrong in some of their interpretations.”

Macchiarelli, for his part, denounces what he considers “conflicts of interest” in the history of Sahelanthropus. “Fossils and scientific discoveries are not only a wealth, a collective achievement for everyone, but for some they can be valuable bargaining chips to obtain positions, financing and more influence, not only to produce knowledge,” he says. “Paleoanthropology is deeply affected by competition and politics, it is hardly ‘neutral’,” he concludes.

Williams believes that the history of this fossil will change when the pelvis is found and predicts that it will be “intermediate” between Ardipithecus and chimpanzees. It is the missing piece to resolve this fight of more than two decades, and settle the enigma of the origin of bipedalism.