For decades, it was an intermittent promise: it dazzled in laboratories, went out in technological winters, and came back on with each leap in computing power. Today that promise is a reality, which forces us to rethink multiple aspects of our society and thus optimize the delicate balance between risk and opportunity that always accompanies technological revolutions. This is especially true in research, where machine learning models (which underpin modern artificial intelligence) have recently been used to support the production of original mathematical proofs.

Until recently, AI has played a less visible role in mathematics than in other scientific areas. The origin of this gap is in the very roots of artificial intelligence, which contrast with those of other more traditional areas of computing. While the latter are based on mathematical logic, through the founding works of Alonzo Church, and, later, , machine learning systems have very different origins—also mathematical—. These models arise from statistics and, particularly, from the need to extract reliable predictions from large volumes of noisy data. Therefore, since its origin, machine learning has been underpinned by a compromise between precision and tolerance for error, very different from the classical ideal of mathematics, built on demonstrations “hard and clear as diamonds,” in words attributed to the English philosopher John Locke.

However, despite this, in recent years deep learning techniques have been incorporated into research work in mathematics to accelerate essential processes, such as the identification of patterns and conjectures, the generation and debugging of ideas or the production of code. These systems (which do not understand the ) perform a wide range of numerical calculations effectively using simple correlations, although they fail grotesquely when they stray outside of learned territory.

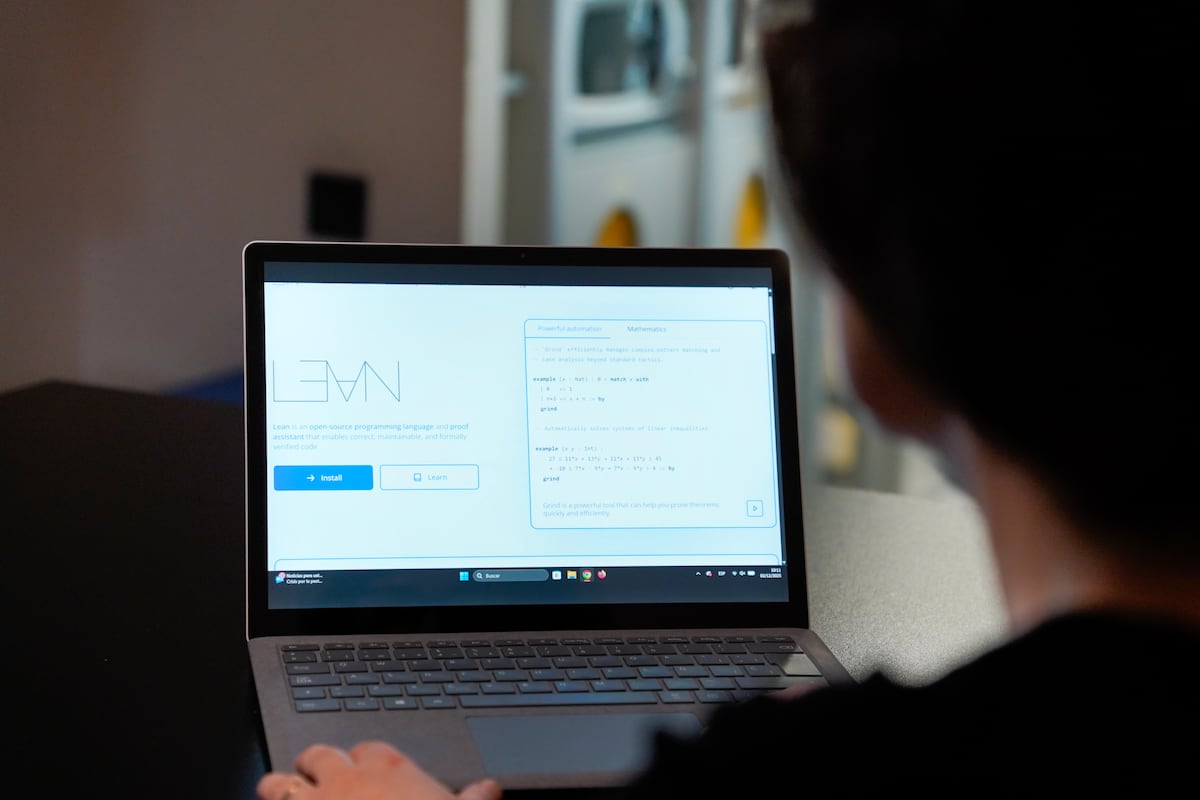

Recently, it has gone one step further: language models are now capable of creating demonstrations autonomously, which can be relevant either by themselves or as auxiliary steps on the way to a more complex result. Additionally, these tests can be verified with tools such as , software that translates mathematics into code that computers can check step by step to ensure that there are no errors.

Everything indicates that these capabilities will expand rapidly, although we still do not know where their limits lie or how far artificial intelligence can go in generating truly new ideas. Will we be faced with systems that are undoubtedly useful, but intrinsically limited, or before “Silicon Einsteins” capable of autonomously producing the great ideas that will shape our culture? Rather than getting lost in a debate about the essence of the human being and the limits of cognition, it is urgent to act judiciously to mitigate the risks and take advantage of the opportunities that this technology offers to mathematics research.

First of all, it is worth remembering that mathematics not only benefits from the advancement of l, but also offers an exceptional testing ground for its development. Just like chess, go or image recognition served to train the first generations of algorithms, mathematical reasoning—due to its clarity and structure—is now emerging as a new laboratory for AI. More transparent and reliable technologies and a better understanding of how the machine reasons could be born from the dialogue between mathematics and AI. Promoting the encounter between these two disciplines, both in the business field and in basic research, is, therefore, an urgent task. And this synergy can only thrive with strong and sustained support for both areas separately.

On the other hand, the arrival of generative artificial intelligence allows mathematicians to free up time from routine tasks and dedicate it to more important objectives. Superficial ideas or repetitive developments risk becoming as obsolete as the ponderous calculations of the admirable “human calculators” portrayed in the film. Hidden Figures. It now offers a rare opportunity to focus on what is essential: to think more deeply, to distinguish what is important from what is incidental, and to cultivate an intuition capable of guiding the machine rather than being guided by it.

Indeed, this type of knowledge (which has to do not only with what we know, but with how we know it) is the most valuable in the era of artificial intelligence: vision, intuition, depth or the ability to grasp contexts. These qualities also differentiate, according to Dreyfus’ model of skill acquisition, the expert from the beginner. For this reason, artificial intelligence multiplies the reach of the expert, but, in the hands of the beginner, it can be limited to amplifying his noise.

This reflection affects both the way we do research and the way we teach and learn mathematics, inside and outside the classroom. The key will be to develop the intuition and flexibility that distinguish the true expert, a task where artificial intelligence can also serve as an accelerator. This represents a profound change with respect to traditional educational models, which were content with providing the beginner with a basic competence. Today the challenge is different: shorten the path to genuine understanding.

Alberto Encisoresearch professor at Higher Council of Scientific Research (CSIC) in the Institute of Mathematical Sciences (ICMAT), where he directs the FLUSPEC project of the European Research Council (ERC), and corresponding academic of the Royal Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences from Spain.

Editing and coordination: Timon Agate (Institute of Mathematical Sciences)

is a section dedicated to mathematics and the environment in which it is created, coordinated by the Institute of Mathematical Sciences (ICMAT), in which researchers and members of the center describe the latest advances in this discipline, share meeting points between mathematics and other social and cultural expressions and remember those who marked its development and knew how to transform coffee into theorems. The name evokes the definition of the Hungarian mathematician Alfred Rényi: “A mathematician is a machine that transforms coffee into theorems.”