The best explanation we have today about the composition of the Universe and how it holds together, the so-called Standard Model (MP) predicts that the millions of substances we know are reduced to just 17 fundamental particles (such as electrons, quarks and the Higgs boson).

It’s the same as saying that, if you could “break” everything that surrounds us — such as trees, stars, people and cell phones — into smaller pieces, you would inevitably arrive at those “fundamental LEGO pieces”. In addition to defining what they are, the MP also clarifies how these particles interact.

To explain why electrons stick together or why there is radioactivity and nuclear fusion in stars, this fundamental theory of physics predicts three of four forces that govern these parts: the Electromagnetic Force, the Strong Force and the Weak Force. Gravity is still a blank page in the MP.

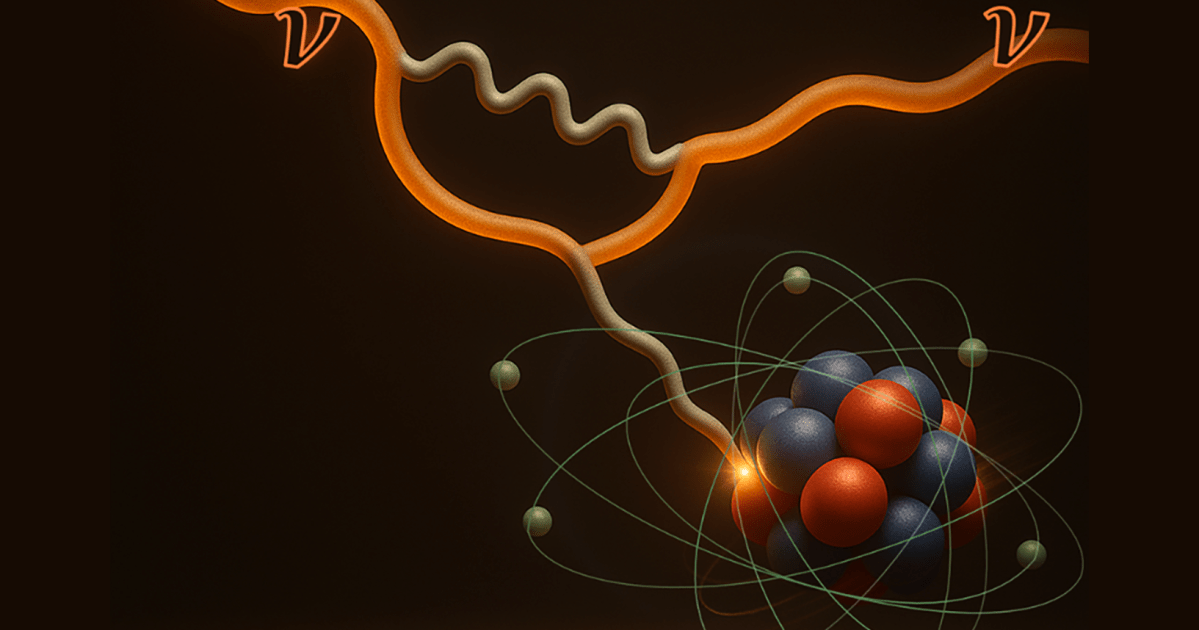

One of the most complex parts of the model, the so-called Electroweak Theory, demonstrates, in a unified way, that the weak nuclear force and electromagnetism are, in essence, two sides of the same coin. But despite having passed thousands of tests, the theory presents some “anomalies” in the neutrino sectorknown as “ghost particles”.

In a recent paper, Italian scientists performed “the first global fit of neutrino-nucleus and neutrino-electron elastic scattering data to further test the MP within a consistent framework,” the authors say in a statement.

Measuring the electrical charge of a neutral particle?

Until now, testing the properties of neutrinos was carried out in a fragmented way, analyzing isolated experiments. The great innovation of this new work was the realization of the first “global adjustment”: the researchers combined data from several experiments around the world into a single consistent theoretical framework.

Considered one of the most fascinating particles in the Universe, the neutrino is invisible, has almost zero mass and practically does not “bump into” anything during its trajectory. In other words, at this very moment, trillions of them coming from the Sun are crossing your body, the ground, and leaving the other side of the Earth, without touching a single atom.

After its experimental confirmation, in 1956, by Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan, based on different approaches, which allowed its observation in nuclear reactors, particle accelerators, or directly from the Sun.

One of the central points of the study is the so-called neutrino charge radius. Although it may seem counterintuitive, because neutrinos have no electrical charge (they are neutral)“in quantum field theory, even an electrically neutral particle can have an effective and measurable charge radius”, explains Nicola Cargioli, researcher at the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN).

In fact, the study confirmed that for electron and muon neutrinos, this trail is in line with theoretical predictions. Using data from dark matter detectors, scientists have established “the most stringent limits in history” for the tau neutrino charge radius by indirectly analyzing signals from accidentally captured solar neutrinos.

When the answer is double, the mystery increases

The study revealed an intriguing result: the current data allows for two possible interpretations. The first fits perfectly into the Standard Model. The other is the so-called degenerate solution — a mathematical “twin” with inverted valuesbut which produces the same effect on detectors.

Although this may seem like a failure, in science it is a golden opportunity. The researchers demonstrated that it will be accurate enough to resolve this “tie” and confirm whether the MP will prevail or whether it will need to be rewritten.

Understanding the fundamental properties of the neutrino is not just an academic exercise. “As we move into the age of precision, this work demonstrates the crucial need to adequately account for all energy effects to avoid misinterpretations of data,” the authors highlight in the paper.

Even without definitive proof, this small detected deviation acts as a signal. “It will be up to future experiments to clarify whether we are observing a statistical fluctuation or a real deviation from the Standard Model predictions”, explains in a statement the first author of the work, Mattia Atzori Corona, from INFN Rome.

Be that as it may, science emerged victorious in this dispute for the best observation of the “invisible”. The study not only validated what we already knew, but pointed the telescope — and the microscope — exactly where the next big discovery in physics should emerge, which is fundamental when it comes to “ghosts”.