WUXI, China — The origins of China’s dominance in rare earths can be traced back to an iron ore mine near Baotou in the north of the country, 50 miles from the border with Mongolia.

It was April 1964 and Chinese geologists had discovered that the mine was also home to the world’s largest deposit of rare earths, a set of 17 metals that have become essential ingredients for today’s global economy. Deng Xiaoping, then a senior Chinese Communist Party leader, visited the remote desert mine belonging to a military steel mill to inspect the enormous treasure.

Also read:

Continues after advertising

“We need to develop steel, and we also need to develop rare earths,” declared Deng, who more than a decade later would become China’s top leader.

Rare earth metals and the magnets made from them are widely used in a long list of civilian and military applications, from cars to fighter jets.

China’s position as a top supplier has given the country enormous power over manufacturing and leadership in clean energy technologies such as electric cars and wind turbines. Companies around the world depend on Chinese exports of these magnets.

China’s centrality in rare earths did not happen by chance. It is the result of decades of planning and investment, inside and outside the country, often directed by the highest levels of the Chinese party and government.

In the early 1970s, the People’s Liberation Army launched a little-known research program to develop possible military uses for rare earths.

Deng continued to drive Chinese advances in rare earths in the 1980s and 1990s, together with Wen Jiabao, a geologist by training who would become China’s prime minister from 2003 to 2013.

Continues after advertising

Under Wen, China consolidated what was a highly fragmented network of mostly private companies into a tightly controlled arm of the Chinese government. Wen closed mines operated by smugglers and faced the industry’s worst pollution. The industry grew in size and specialization.

In 2019, seven years after becoming China’s top leader, Xi Jinping described rare earths as “an important strategic resource.” And it has shown over the past year that it is willing to use rare earths as a chokehold on global supply chains and a powerful weapon in the trade war with President Donald Trump.

In April and again in October, China enacted new export controls that allowed it to withhold supplies of rare earths and rare earth magnets and force Trump to concede on tariffs. The October order “pointed a rocket launcher at the supply chains and industrial base of the entire free world,” said Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent.

Continues after advertising

Not since the Arab oil embargo of late 1973 and early 1974 has the United States faced such a drastic loss of access to critical minerals. And although the oil embargo has affected a third of the world’s oil supply, China produces 90% of the world’s rare earths and rare earth magnets.

China’s actions in 2025 regarding rare earths were “undeniably a great moment in geoeconomic history and international relations,” said Nicholas Mulder, a historian of embargoes and sanctions at Cornell University.

Early role for China’s military

China’s rare earths industry advanced in a military effort more than 50 years ago, during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s Red Guards had virtually closed most schools and universities. It seemed like an unlikely time for a technological breakthrough.

Continues after advertising

The father of the industry was Xu Guangxian, a tall, thin man from Shaoxing, a city near Shanghai. He loved Go, an ancient Chinese board game, and devoured martial arts novels.

Shortly after World War II, Xu completed a doctorate in chemistry at Columbia University. He returned to teach and do research at Peking University. Xu discovered a new way to process uranium, a breakthrough in China’s efforts to build an atomic bomb that anticipated the role he would later play in rare earths.

Then, like many intellectuals, Xu was arrested during the Cultural Revolution. But, in 1971, he was politically rehabilitated and returned to Peking University. The People’s Liberation Army had a task for it: invent a new way to refine pure samples of rare earth metals. The Chinese military wanted these samples to experiment with lasers for battlefield use.

Continues after advertising

Purifying rare earths is extraordinarily difficult. Early chemists called them rare not because they were difficult to find — they are not — but because of the difficulty of separating them from one another.

At Peking University, Xu and his wife, Gao Xiaoxia, also a high-level chemical engineer, locked themselves in a laboratory. They achieved a revolutionary breakthrough: rare earths could be purified using cheap hydrochloric acid and simple, improvised plastic tanks.

The Xiaopings

After Mao’s death, Deng began consolidating power with an economic program that emphasized science and technology and appointed Vice Premier Fang Yi to lead him in 1978. Fang traveled with a delegation of scientists and engineers to Baotou to inspect the rare earth industry.

A five-year plan drawn up by Deng and Fang, covering 1981 to 1985, called for China to “increase production of rare earth metals.”

Rare earths were then used in relatively simple manufacturing, to make steel stronger, to refine petroleum and to polish glass.

But in laboratories in Michigan and Japan, engineers were beginning to discover how to turn rare earth metals into extremely powerful magnets. Rare earths were about to become central to advanced manufacturing and the creation of a modern world of computers, smartphones and cars.

In 1983, engineers at General Motors and Japanese magnet manufacturer Sumitomo Special Metals announced that they had developed powerful rare earth magnets. They were immediately applied to electric motors in the automotive industry and beyond.

China did not have the expertise to transform rare earths into magnets. She would buy this knowledge from the United States.

At GM you know dinner, at China he enters

General Motors had turned his discovery into a thriving magnet-manufacturing subsidiary in Indiana called Magnequench. But a decade later, GM decided to stop making many of its own auto parts.

Magnequench was sold in 1995 to a consortium of investors that included two Chinese companies led by Deng’s sons-in-law: Wu Jianchang and Zhang Hong. Under President Bill Clinton, the U.S. government allowed the transaction to move forward because the majority of owners were Americans.

The American owners were mainly institutional investors. Deng’s sons-in-law led companies with deep ties to low-cost magnet production in China. Magnequench began moving its equipment in 2001 to Tianjin and Ningbo, China, and closed in Valparaiso, Indiana, in 2004.

The move by Magnequench, which was later purchased in 2005 by a Canadian rare earth processor with operations in China, taught China how to make rare earth magnets.

China tests a commercial weapon

In late September 2010, two dozen of the most powerful executives in China’s rare earths industry were summoned to a meeting room in China’s Ministry of Commerce, a Stalinist-style building in the heart of Beijing. China faced Japan over uninhabited islands north of Taiwan.

A senior ministry official gave his orders to the executives: no more exports of rare earths to Japan, its biggest market. No extra exports to other countries that could pass on supplies to Japan. And no word should be said publicly about the ban.

The embargo was never formally announced, but it forced the Japanese government to concede on the territorial issue after two months. Still, the move also revealed Beijing’s weakness.

Chinese crime syndicates, which controlled about half of the country’s rare earths production, continued to smuggle rare earths from China to Japan even during the embargo.

Wen ordered police operations to dismantle the unions. Security forces have raided illegal mines and placed them under Beijing’s direct control.

After 15 years, it is clear that the embargo on Japan was a turning point for the Chinese rare earths industry. Previously lawless areas of industrial activity were tamed and brought under government control, and Beijing learned that it could use this control to force geopolitical and commercial partners to yield.

The future of China: education and research

Today, China is working to consolidate its leadership in rare earths by training more technicians and researchers than any other country. Rare earth programs are offered by 39 universities.

The United States and Europe have no such programs — not even at Iowa State University, an institution that has trained generations of American rare earth engineers.

Iowa State has not offered a course on the topic in several years and has a single graduate student doing independent study in the field. It plans to offer a course in 2026.

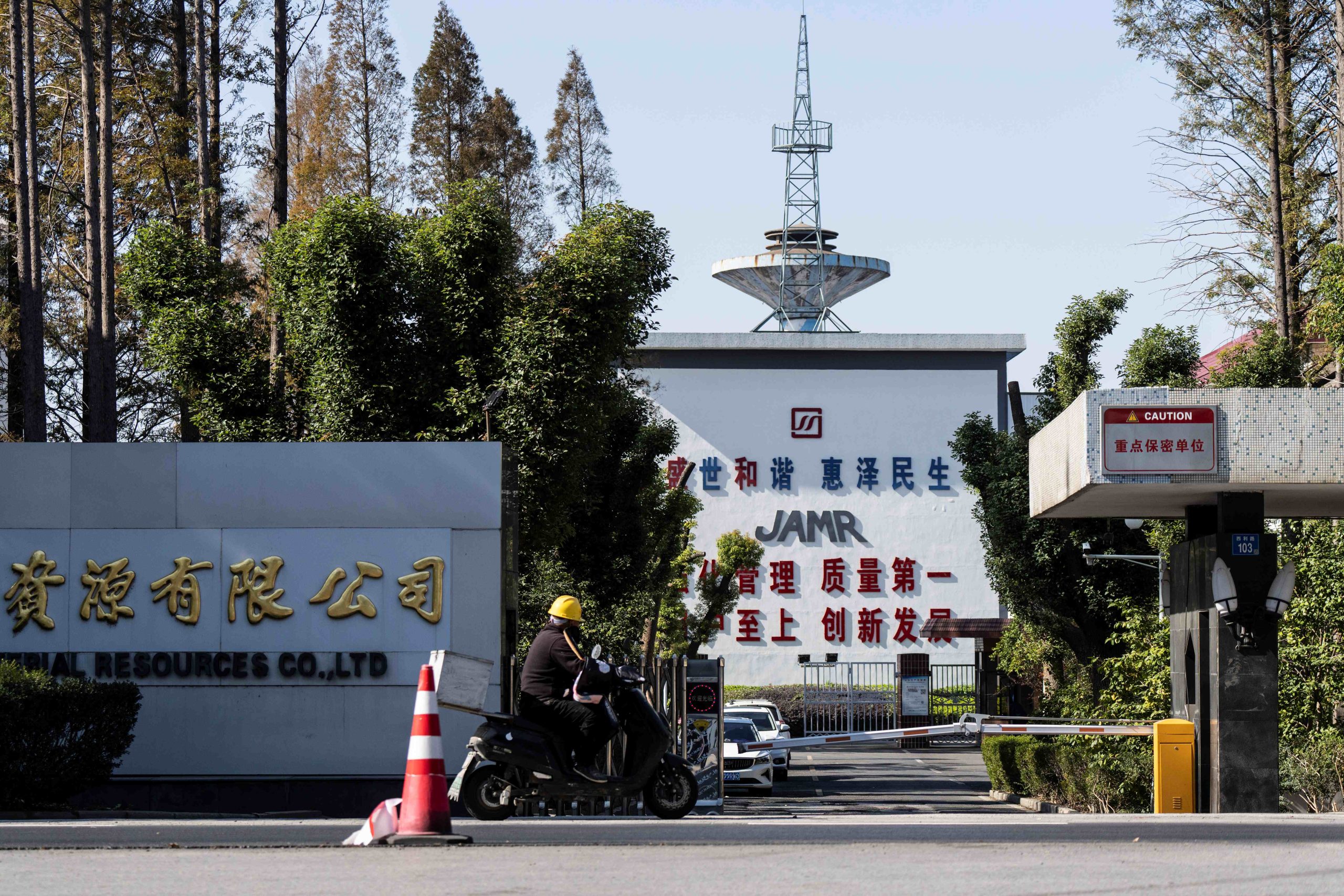

China has hundreds of scientists researching rare earth technologies. Technicians at a refinery in Wuxi, a city near Shanghai, spent seven years experimenting to refine dysprosium, a rare earth, to an extraordinary level of purity.

The refinery is today the only world source of this element, used in capacitors — small devices that control electricity — present in Nvidia’s Blackwell artificial intelligence chips.

The majority of the refinery’s shares were owned until 2025 by Neo Performance Materials, the Canadian company that acquired Magnequench in 2005.

A state-controlled Chinese company bought most of the shares on April 1. Then, on April 4, Beijing halted exports of dysprosium and six other rare earths to the United States and its allies.

China is determined to protect its technological leadership. Beijing has halted most exports of rare earth processing equipment. It also confiscated the passports of technicians in the sector to prevent them from leaving the country with valuable information.

During a late November visit to the Wuxi refinery, a shiny steel national security sign on the entrance gate warned: “Attention: Key Unit Confidential.”

c.2026 The New York Times Company