Immortalized by Carl Sagan — the presenter of the TV series Cosmos: a personal journey in the 1980s — the phrase “we are made of stardust” is much more than a poetic message. It is actually a proven scientific fact and one of the pillars of modern astrophysics.

You don’t even need to be a scientist to understand that, if shortly after the cosmos contained only 75% hydrogen and 25% helium, then elements such as the oxygen we breathe, the carbon that forms our DNA and the calcium in our bones were manufactured later in the “kitchens of the Universe”: the stars.

Now, a study led by researchers at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden has raised an important question: “Starlight and dust are not enough to drive the powerful winds of giant stars, responsible for transporting the basic components of life across our galaxy,” the statement says.

In other words, for stardust to reach Earth — or even form Earth — she needs to get out of the star first. And then the first big obstacle arises: as they are huge, stars have a very strong gravity that tries to pull everything back to the center

Testing the old theory on a red giant star called R Doradus, he concludes that “dust alone cannot drive the wind in this star and that additional mechanisms may be needed.”

Small and transparent: R Doradus dust defies the laws of stellar wind

Understanding the origin of life on Earth necessarily involves the way in which giant stars — factories of chemical elements — feed their winds. Without these winds, (which will be the final destination of R Doradus), that is, it would never reach us.

Until now, the theoretical explanation of this phenomenon was simplistic: the star makes atoms (carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and others), the star’s light (photons) hits these grains as if they were billiard balls, and this constant impact of light pushes the dust away. This, in turn, drags the gas along, creating the wind.

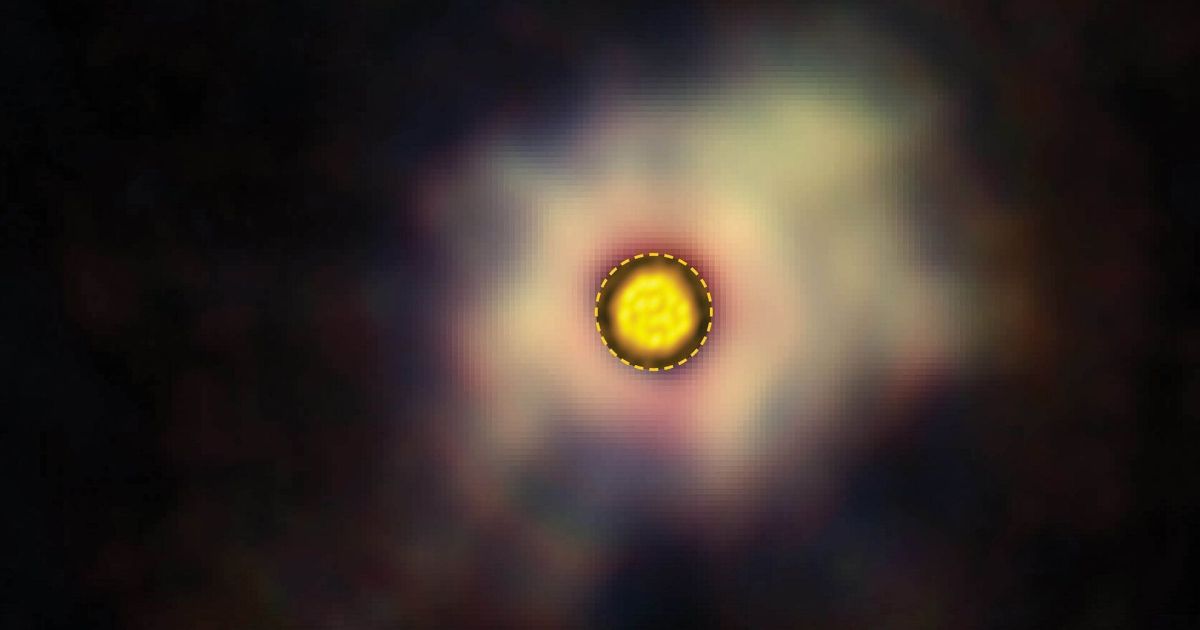

But the study of R Doradus — a giant oxygen-rich star located about 192 light-years from Earth — has called this traditional view into question. Using the SPHERE/ZIMPOL instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, the team obtained very high-resolution images of the polarized light reflected by the dust around the star.

For the authors, there are two problems with our stellar neighbor. The first is transparency: because the dust around the star is composed of iron-free silicates and aluminum oxide, these materials have low light absorption. Almost transparent, they do not absorb enough energy to be pushed, nor are they propelled by the scattering (reflection) of light.

Furthermore, in order for the light to “hit and bounce” (scatter), it is physically necessary for these grains to have a specific size which, according to previous theory, should be at least 0.3 micrometers. But current measurements have revealed that they are smaller than that, at about 0.1 micrometers.

Who brought the stardust that formed us?

By combining observations with advanced computer simulations, “we were able, for the first time, to carry out rigorous tests to see whether these dust grains can sense a sufficiently strong pull from the star’s light,” says the study’s first author, Thiébaut Schirmer from Chalmers.

The results are disconcerting: If the dust is too small to be pushed by light, but the star continues to emit winds and lose mass, then the “light pushes dust” theory cannot be the main cause of the wind, or at least does not work on its own.

This means the theory we have been using for decades to explain how stars spread the elements of life throughout space. In other words: we still cannot fully understand how the material that forms us came from the stars.

But, to the poets’ delight, the current article does not dispute the idea that “we are made of stardust.” In fact, it reinforces it, but it makes the explanation of how this dust reaches us much more complex and interesting, as astronomers were forced to look for a plan B.

It may be that, for the star’s carbon and oxygen to form planets and living beings, they need a “jolt”, which can be a chaotic and turbulent process. This means the star could be boiling (and emitting bubbles), having pulsations that act as a springboard, or experiencing flares and dust explosions.

In any case, if the “state of the art” in force so far has failed with the star R Doradus (which is the easiest to study), it is very likely that it will be wrong or incomplete for all other stars of the same type in the Universe. So we have to go back to researching which delivery brought us here.