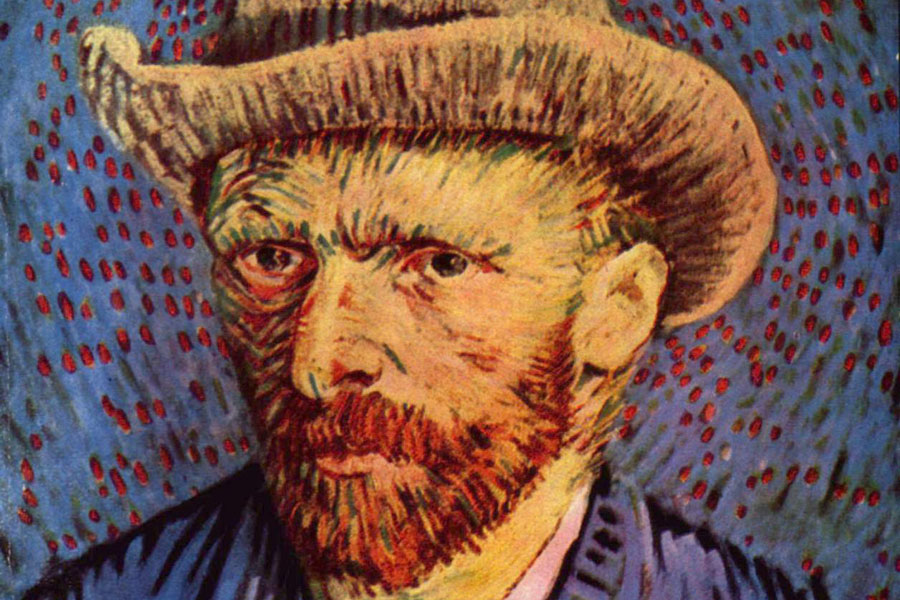

Auto-Retrato de Vincent Van Gogh

Although there are some common genes that are associated with mental illness and creativity, there is little scientific basis behind the stereotype of the tortured, crazy artist.

Vincent van Gogh cut off his own ear with a knife during a psychotic episode. Dancer Vaslav Nijinsky developed schizophrenia and spent the last 30 years of his life hospitalized. Virginia Woolf lived with bipolar disorder and ended up taking her own life when she felt the beginning of a deep depression.

Many famous artists lived with serious mental illnesses. Catherine Zeta-Jones, Mariah Carey, Demi Lovato, Jean-Claude Van Damme and Mel Gibson reported having diagnoses of bipolar disorder. Yayoi Kusama, Sylvia Plath, Kurt Cobain and Syd Barrett spoke about psychotic experiences. There is much speculation about whether Amy Winehouse, Marilyn Monroe and Ernest Hemingway also suffered from borderline personality disorder.

The concept of “crazy creative genius” dates back to Antiquity. Renaissance and Romantic artists sometimes took on eccentric personalities to stand out as extraordinary individuals who had made Faustian pacts for their talents.

Edvard Munch, the Norwegian painter, described his “sufferings” as “part of me and my art… their destruction would destroy my art”. The poet Edith Sitwell, who suffered from depression, used to lie in an open coffin to inspire your poetry.

In 1995, a study of 1,005 biographies written between 1960 and 1990 even suggested that people in creative professions had a higher rate of psychopathology severe than the general population.

So how does this square with the fact that artistic expression is beneficial to our mental health? The new book, Healing Arts: The Science of How the Arts Transform Our Health, explains that there is a wide range of scientific evidence about these benefits.

However, the reality for professional artists can be a little different. Although they tend to report greater overall well-beingthe life of an artist can be psychologically challenging. They have to deal with everything from precarious careers to professional competition.

Furthermore, the fame brings stresschallenging lifestyles, a greater risk of substance abuse, and an inevitable but harmful focus on oneself. In a 1997 study, scientists analyzed the number of first-person pronouns – I, me, my, mine and myself – in the songs of Cobain and Cole Porter (who also had episodes of severe depression). As their fame increased, both showed a statistically significant increase in the use of these pronouns.

The link between art and serious mental illness

But what about artists who developed mental illnesses before they became famous, or even before they became artists? Genetic research has discovered some shared genes which can underlie serious mental illness and creativity.

One variation in the NRG1 gene it is associated with both a greater risk of psychosis and higher scores on questionnaires that measure people’s creative thinking. Variations in dopamine receptor genes have been associated with both psychosis and various creative processes, such as novelty seeking and decreased inhibitions. However, the results are contradictory – not all studies show these links.

In addition to genetics, there are also some personality traits that can be common to both mental illness and creativityincluding openness to experience, the search for novelty and sensitivity. It is possible to see how this research could provide a new perspective for understanding artists such as Van Gogh, Nijinsky and Woolf.

However, creativity and mental health difficulties can conflict. For example, Woolf described her depressive episodes of bipolar illness as a well: “Down there, I can’t write or read“.So while some people with serious mental illness can create art, not everyone can always do so.

Furthermore, when we look for evidence of a link between serious mental illness and creative activities at the population level, evidence is not conclusive. In 2013, a Swedish study tracked more than 40 years of data from 1.2 million people in national patient registries, including medical records with diagnoses, mental health treatments and causes of death.

Researchers found that people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, anxiety disorders, and unipolar depression actually had less likely than average of the population to pursue creative professions. The only small exception was bipolar disorder, where people were about 8% more likely to be in a creative profession.

But this study also discovered something possibly more intriguing: parents and siblings of people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder were more likely to be in creative professions. It’s not difficult to think of examples among famous artists: James Joyce’s daughter and David Bowie’s half-brother had schizophrenia. Why does this pattern exist?

People who are genetically susceptible to serious mental illnesses, but who do not develop full symptoms, may present lighter versions. Mild hypomania, for example, involves elevated mood states, but not with the intensity of bipolar disorder. Schizotypy involves divergent thinking and heightened emotions, without the severity of schizophrenia.

These conditions have been associated with creative processes, such as reduced inhibitions, unfocused attention and neural hyperconnectivity (the ability to make intersensory associations, such as hearing colors or tasting musical notes).

Perhaps siblings and parents of people with mental illnesses are more likely to have these conditions, which would explain why they choose creative professions. That being said, Not all creative people work in creative professions – for many, creative hobbies are an escape valve from work.

Essentially, science suggests that there may be some shared processes between serious mental illness and creative processes, such as the arts. But this is not the clear connection that personal stories might lead us to believe. THE myth of the “mad creative genius” It’s too simplistic. This also risks perpetuating stigma rather than promoting understanding, so it may be best to leave this idea alone.

It seems more productive to focus on the value that creative engagement can bring to supporting our mental health. Whether for people with mental illnesses or simply for those dealing with day-to-day mood swings and emotions, each week more studies emerge that broaden our understanding of tangible and significant benefits that the arts can provide. This research reveals how artists, healthcare professionals and communities can work together to build safe, accessible and inclusive opportunities to enjoy the arts.