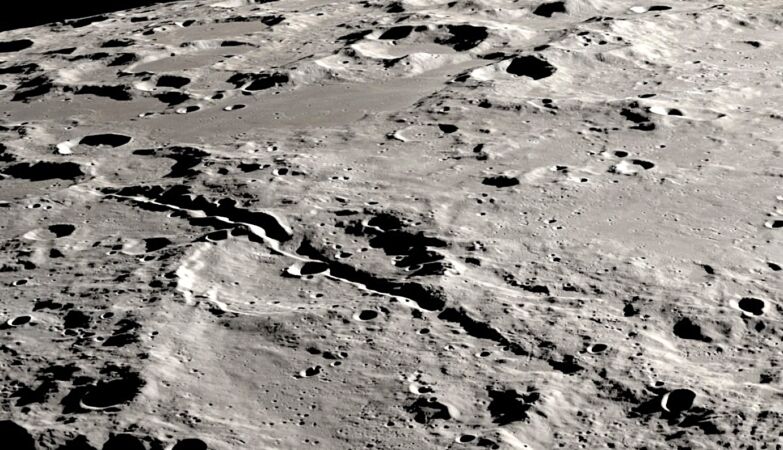

Ernie T. Wright / SVS / NASA

Vallis Schrödinger lunar formation

A new study reveals a major problem in the study of samples from the Moon, which will inevitably be contaminated by methane released by the rockets carrying the probes or astronauts.

There is a fundamental tension in space exploration that has generated ongoing debate for decades. When we create the necessary infrastructure to explore other worlds, we end up damaging them in some way, making them less scientifically interesting or less “untouched”, which, in itself, some would argue is a negative thing.

A new one published in JGR Planets, authored by Francisca Paiva, a physicist at Instituto Superior Técnico, and Silvio Sinibaldi, responsible for planetary protection at the European Space Agency (ESA), argues that, at least in the case of the Moon, the The problem is even worse than you thought initially.

The article analyzes how methane, one of the main exhaust gases used in the descent and launch of lunar probes, spreads across its surface. In particular, it looks at how this organic compound can accumulate in Permanently Shadowed Regions (PSRs), which are thought to harbor early ice from the formation of the solar system, which could provide information about prebiotic molecules that were common in the solar system before the development of life on Earth.

The authors developed a model that would track how methane would migrate from the landing site of a lunar module, such as Argonaut, ESA’s main lunar module, scheduled to launch in 2031 in support of the Artemis program. They found that, regardless of where the module landed, a significant amount (more than 50%) of the methane produced during descent would end up in a region of pre-polar descent (PSR).

Fraser talks about the ice hidden in the Moon’s PSRs.

That’s a problem. THE methane would confuse studies scientific studies of organic molecules in these otherwise pristine ices. Every time a scientist took a core sample and found a sign of methane, he would have to question whether it came from ancient prebiotic chemistry or simply from the rocket that took his instruments there.

Remarkably, even landings at one pole sent methane across the lunar surface to accumulate in PSRs at the opposite pole. For example, in a landing at the south pole, around 42% of the methane generated during the descent it ended up in methane reservoirs at the south pole, while 12% ended up in reservoirs at the north pole. Essentially, no matter where it lands on the lunar surface, it will contaminate everything with organic compounds that could confuse future biological researchers.

Perhaps even more shocking is the fact that this process was quick. They found that the average time for a methane molecule to go from the lunar south pole to the north pole was just 32 Earth days. The simulation on which the article is based, which resulted in more than half of the methane released eventually remaining there, lasted just 7 lunar days – approximately 7 Earth months.

The LCROSS mission intentionally launched a projectile into a lunar surface region (PSR) to detect water — this video shows what was observed.

The authors argue that the current Committee for Space Research (COSPAR) rules for planetary protection need to be rethought in light of these simulated results. One of the highest protection levels for lunar exploration is category IIb, for missions that specifically target lunar surface regions (PSRs). In this case, it is necessary to provide COSPAR with a list of organic materials on board of the landing module. However, this does not do much to protect the sites intended for study, much less those that are literally on the opposite side of this small world.

Lunar exploration programs are still expanding, so we still have time to develop a cohesive planetary protection protocol in time to save these untouched and unique places in the solar system. Whether all participants in this new moon race — governments, NGOs and private companies — will agree to these protocols is another question. But articles like this are essential to convince them.