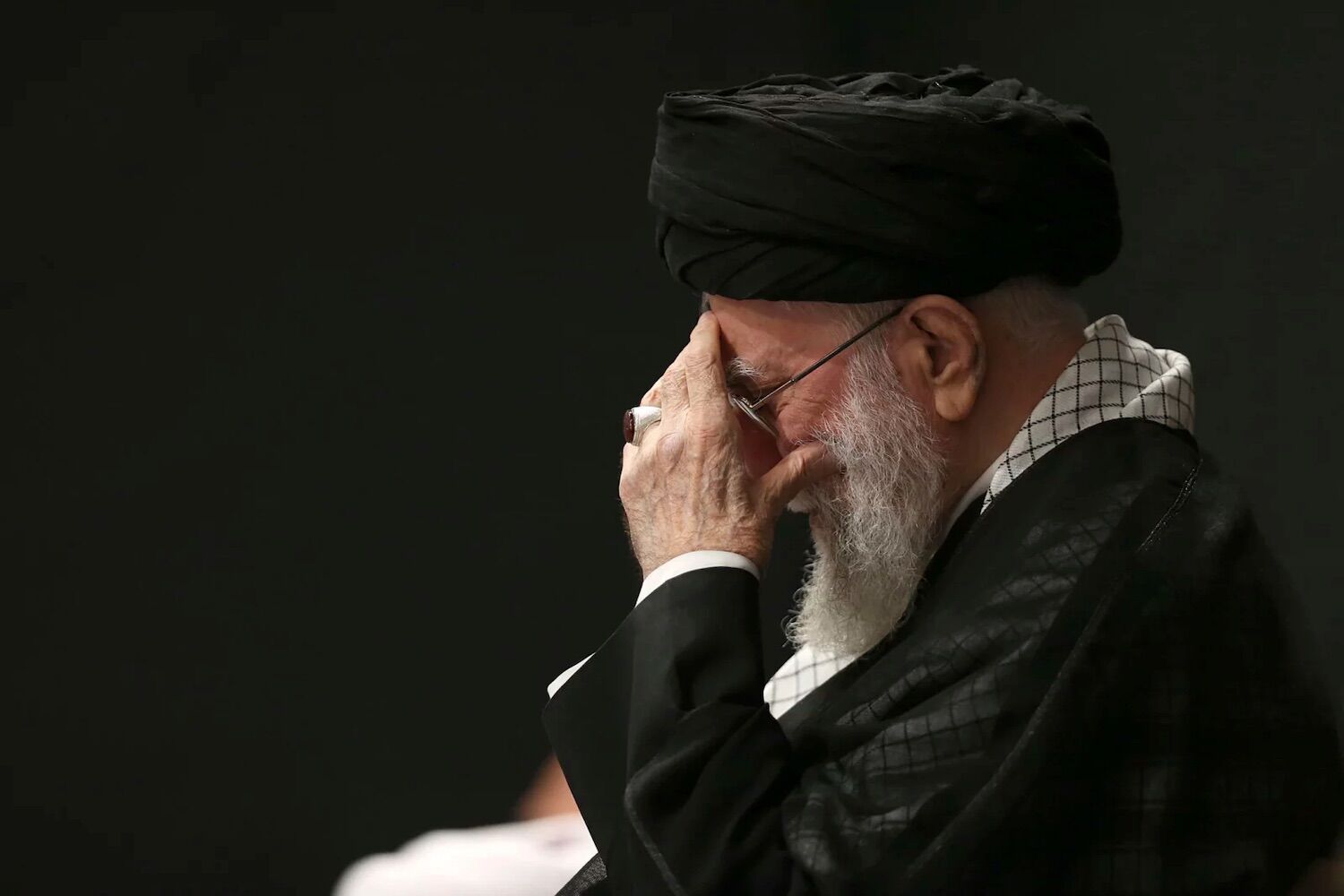

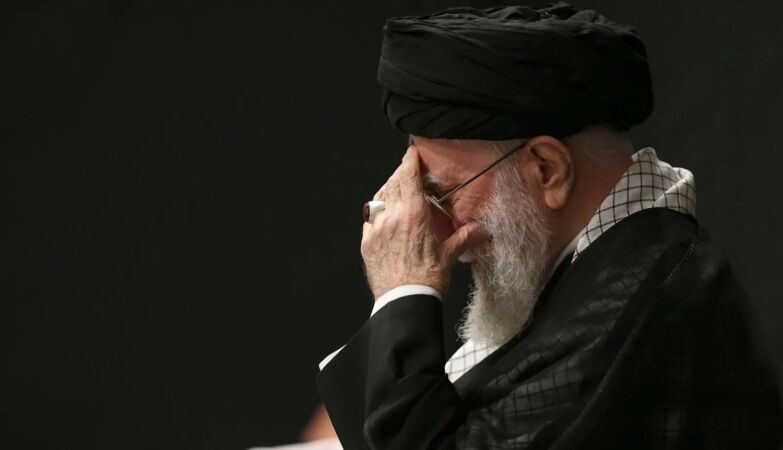

Office of the Supreme Leader of Iran

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Supreme Leader of Iran

Decades of depleting water resources, building dams and repressing scientists and environmentalists have led Iran to ecological crises that are fueling the protests rocking the country.

The anti-government protests sweeping Iran, from big cities to rural locations, are powered by anger in the face of collapse economic and political repression.

But, notes the , behind the headlines about currency devaluations and clashes in the streets lies a deeper and more permanent engine of dissent: ecological calamity.

Decades of ignoring scientists, persecuting activists and greenlighting corrupt development schemes have triggered a water crisis so severe that the president Masoud Pezeshkian has already warned that residents of Tehran may have to , which is sinking as dry aquifers give way.

A devastation extends far beyond Tehran. Lake Urmia, once one of the world’s largest salt lakes, has shrunk to less than 10% of its volume, while the iconic Zayandeh River remains dry for years.

Forest fires devastated the country’s parched forests, classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In the oil-rich Khuzestan province, home to Iran’s Arab minority, the water diversion promoted by the State it devastated the local economy and inflamed ethnic resentments.

Iranians, and many experts, blame the governmentone of the most repressive regimes in the world.

Environmental issues are linked “to all other complaints that activists, citizens and protesters have regarding economic and political issues”, he stated Eric Lobnon-resident researcher at the Carnegie Middle East Program and associate professor at Florida International University. “It’s all interconnected“.

The human cost is staggering. Ruined infrastructurepoorly designed irrigation systems and over-exploited aquifers have left farmers unable to plant crops and cities forced to ration supplies.

Tens of thousands of people, including children, die prematurely every year due to serious water and air pollution. Water shortages and electricity cuts closed companies and left ordinary Iranians “concerned that they had enough water to drinkshower and clean up,” said Lob.

O water stress tIt also became a source of political contestation and a political control toolhe added.

As ethnic minority regions on the periphery of Iran saw its water supply diverted to the central provinces dominated by the Persian majority, creating environmental “winners and losers” and deepening resentment.

In Khuzestan, national government policies have diverted water from the Karun River to central highland provinces, reinforcing the perception that Tehran prioritizes agriculture and industrial interests with political connections to the detriment of local needs.

Gregg Romanexecutive director of the Middle East Forum, pointed to recent protests over access to water in the province of Sistan and Balochistan, where protesters marched in 2023 with signs that read “Sistan is thirsty for water, Sistan is thirsty for attention“.

“Estes are not separate from the current revolt“, Roman said of the previous water protests. “They are precursors. Economic and environmental grievances are inseparable when the tap runs dry and the crops die“.

Student groups they also identified Iran’s ecological emergencies as driving the unrest.

“Today, crises have accumulated: poverty, inequalityclass oppression, gender oppressionpressure on nations, water and environmental crises. They are all direct products of a corrupt and worn-out system,” said student activists in a December statement.

The current protests, which broke out in December, are the biggest since 2022. The Government responded with a blocking communicationscutting internet access across the country, and violent repressions.

Human rights organizations estimate that thousands were killed and even more detainees. Iran has a history of execution of protestersoften by public hanging.

Lob traces a direct line between the current revolt and environmental failures history of the regime.

Since the 1979 revolution, the Government has used rural development projects to increase political legitimacy and popular support — a process that gave rise to a “water mafia” within the military establishment and the construction of hundreds of dams across the country, says Loeb.

“Organizations close to the Government and the military managed to obtain contracts for these projects,” said Lob. “The goal was power and the pursuit of profit rather than environmental protection and sustainability.”

In recent decades, Iran’s regime has survived wars, sanctions and uprisings. In recent weeks, it has faced violent protests, which have caused thousands of deaths, and even led to Donald Trump to repeatedly intervene in the country to overthrow the regime.

Will the environmental crisis finally bring down the ayatolahs’ regime?