And it’s not just Russia and it’s not just the United States. China also has its eyes on the remote region

The debate surrounding the Arctic is becoming more heated than ever, with US President Donald Trump continuing to insist that Greenland become part of the United States. But while Trump’s demands that the US take control of territory belonging to one of its closest and most reliable allies have intrigued the world, the race for the Arctic has been going on for decades.

And for a long time, Russia has been winning it.

There is no doubt that Moscow has had a dominant presence in the Arctic region.

Vladimir Putin’s country controls about half of the territory and half of the maritime exclusive economic zone north of the Arctic Circle. Two-thirds of the Arctic region’s residents live in Russia.

And although the Arctic represents only a small fraction of the global economy – about 0.4%, according to the Arctic Council, the forum representing Arctic states – Russia controls two-thirds of the region’s GDP.

Russia’s military power in the Arctic

Russia has been expanding its military presence in the Arctic for decades, investing in new and existing facilities in the region.

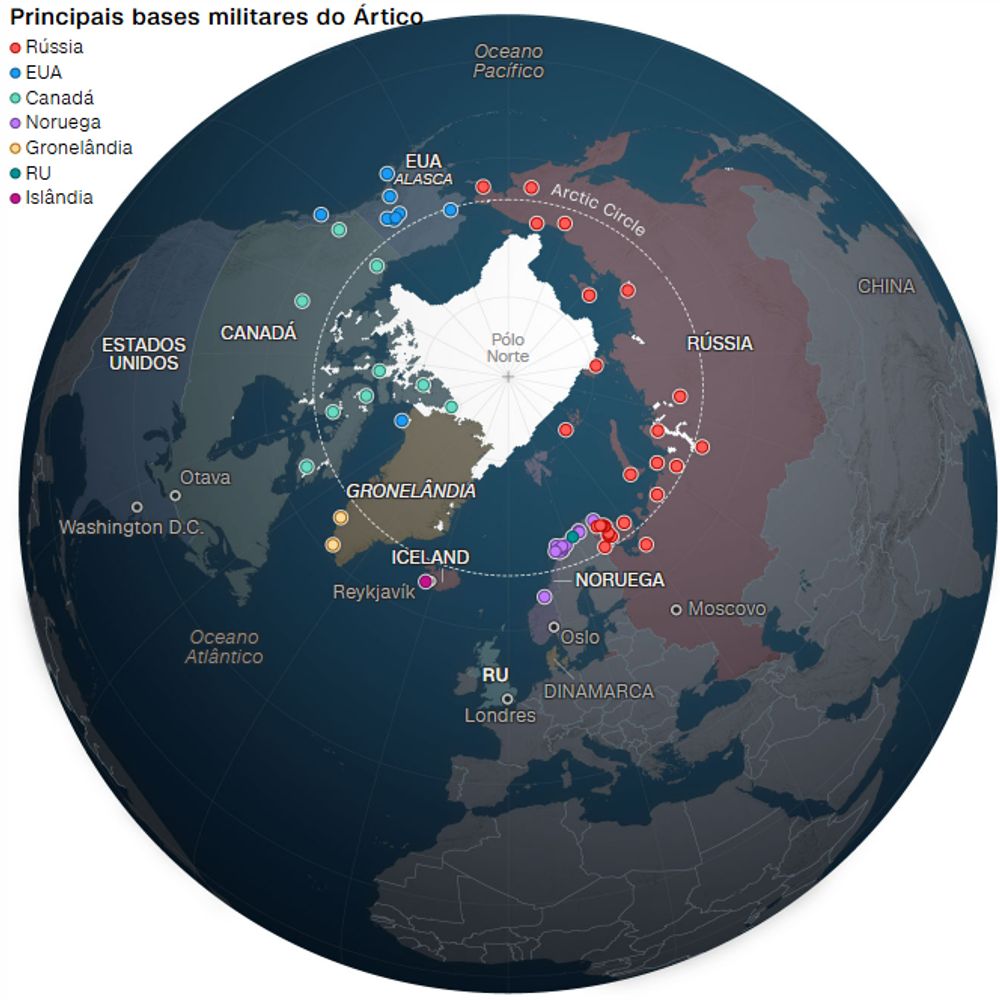

There are 66 military bases and hundreds of other defense installations and outposts in the Arctic region, according to the Simons Foundation, a Canadian nonprofit that monitors nuclear security and disarmament in the Arctic.

Russia and NATO push for a military presence in the Arctic

The Arctic is home to more than 60 major military installations, with hundreds of other defense installations in the broader region, according to the Simons Foundation, a Canadian non-profit organization focused on Arctic security. Russia has at least 30 military installations in the Arctic and has invested heavily in its fleet of nuclear submarines, the backbone of its military power in the Arctic.

Note: The map only shows major military installations and may be incomplete.

Sources: Simons Foundation, Royal United Services Institute

Graphic: Lou Robinson, CNN

According to publicly available data and research by the Simons Foundation, 30 are in Russia and 36 in NATO countries with Arctic territory: 15 in Norway – including a British base -, eight in the United States, nine in Canada, three in Greenland and one in Iceland.

And while not all bases are equal – experts say Russia cannot currently match NATO’s military capabilities – the scale of Russia’s military presence and the pace at which Moscow has expanded it in recent years are cause for great concern.

The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a UK-based defense think tank, says that Russia has in recent years invested a significant amount of money and effort into modernizing its nuclear submarine fleet, which forms the backbone of its military power in the Arctic. As it continues to wage war in Ukraine, Russia has also improved capabilities in terms of radars, drones and missiles.

The situation was not always so dangerous. For years after the end of the Cold War, the Arctic was one of the areas where it appeared that Russia and Western countries might actually do business together.

The Arctic Council, founded in 1996, has attempted to bring Russia closer to the other seven Arctic countries and enable closer cooperation on issues such as biodiversity, climate and protecting the rights of indigenous peoples.

For a time, there was even an attempt to work together on security, with Russia participating in two high-level meetings of the Arctic Chiefs of Defense Forum before being expelled due to its illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Most forms of cooperation have since been suspended, with relations between the West and Moscow reaching a new post-Cold War low after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO in 2023 and 2024 effectively divided the Arctic region into two roughly equal halves: one controlled by Russia and the other by NATO.

Trump has repeatedly stated that the US “needs” Greenland for national security reasons, pointing to Russian and Chinese ambitions in the Arctic. The US president argued that Denmark, which has sovereignty over the largest island in the world, is not strong enough to defend it against threats from the two countries.

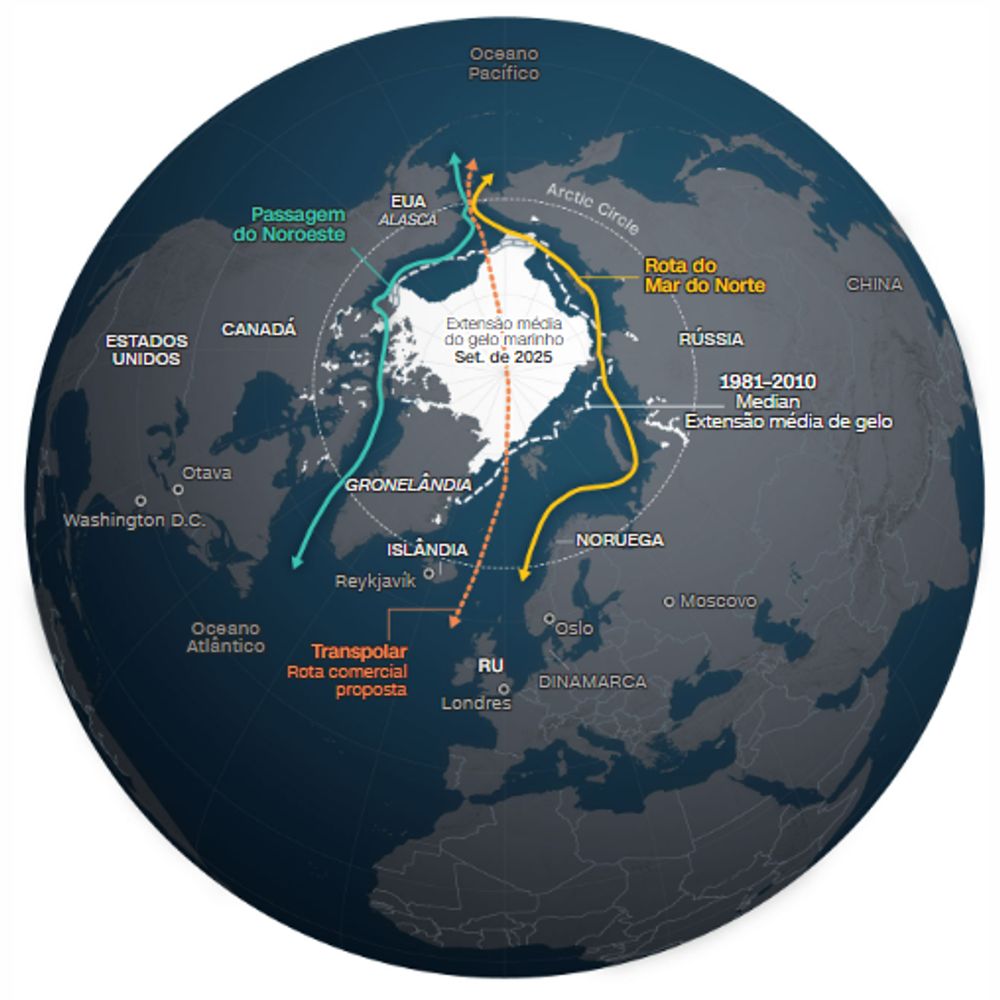

Melting sea ice makes Arctic shipping lanes passable

Shipping routes that would previously have been icy for much of the year are now open due to rising temperatures. The Northern Sea Route shortens sailing time between Asia and Europe to about two weeks, roughly half the time needed via the traditional Suez Canal route.

Sources: National Snow and Ice Data Center, National Geospatial Information Agency

Graphic: Lou Robinson, CNN

Although it is not an Arctic country, China has not hidden its interest in the region. The country declared itself a “near-Arctic state” in 2018 and outlined a “polar silk road” initiative for shipping in the Arctic.

In 2024, China and Russia launched a joint Arctic patrol, part of a broader collaboration between the two countries.

But security isn’t the only reason interest in the Arctic is growing. The region is transforming faster than any other area in the world as the climate crisis worsens, warming about four times faster than the global average.

Sea ice is decreasing at an accelerated rate. But while scientists warn that this situation could have incredibly damaging consequences for the natural world and the livelihoods of the people who depend on it, there are many who argue that melting sea ice could also open up a huge economic opportunity in terms of mining and shipping.

Two shipping lanes that were virtually unviable just two decades ago are now opening up due to dramatic melting ice – although researchers and environmental advocates have warned that sending fleets of ships through this pristine, remote and dangerous environment is an ecological and human disaster waiting to happen.

The Northern Sea Route, which runs along the northern coast of Russia, and the Northwest Passage, which hugs the northern coast of North America, have been virtually ice-free during peak summer since the late 2000s.

The Northern Sea Route shortens navigation time between Asia and Europe to about two weeks, roughly half the time it takes the traditional Suez Canal route.

Although parts of the route were used by Russia during the Soviet period to reach and supply remote locations, the challenges it presented meant it was largely ignored as an option for international navigation.

The situation changed in the early 2010s when the crossing became more affordable, and since then the number of trips through it has increased from a handful a year to around 100.

Russia has intensified its use of the route since 2022, using it to transport oil and gas to China, after sanctions cut it off from its previous European customers.

Likewise, the Northwest Passage has also become more viable, with the number of crossings increasing from a couple per year in the early 2000s to 41 by 2023.

A third, central route, which would take ships directly through the North Pole, could also become possible in the future, although the level of ice melting that would be required to do so would have alarming consequences, accelerating the warming of the planet, increasing weather extremes and decimating the region’s precious ecosystems.

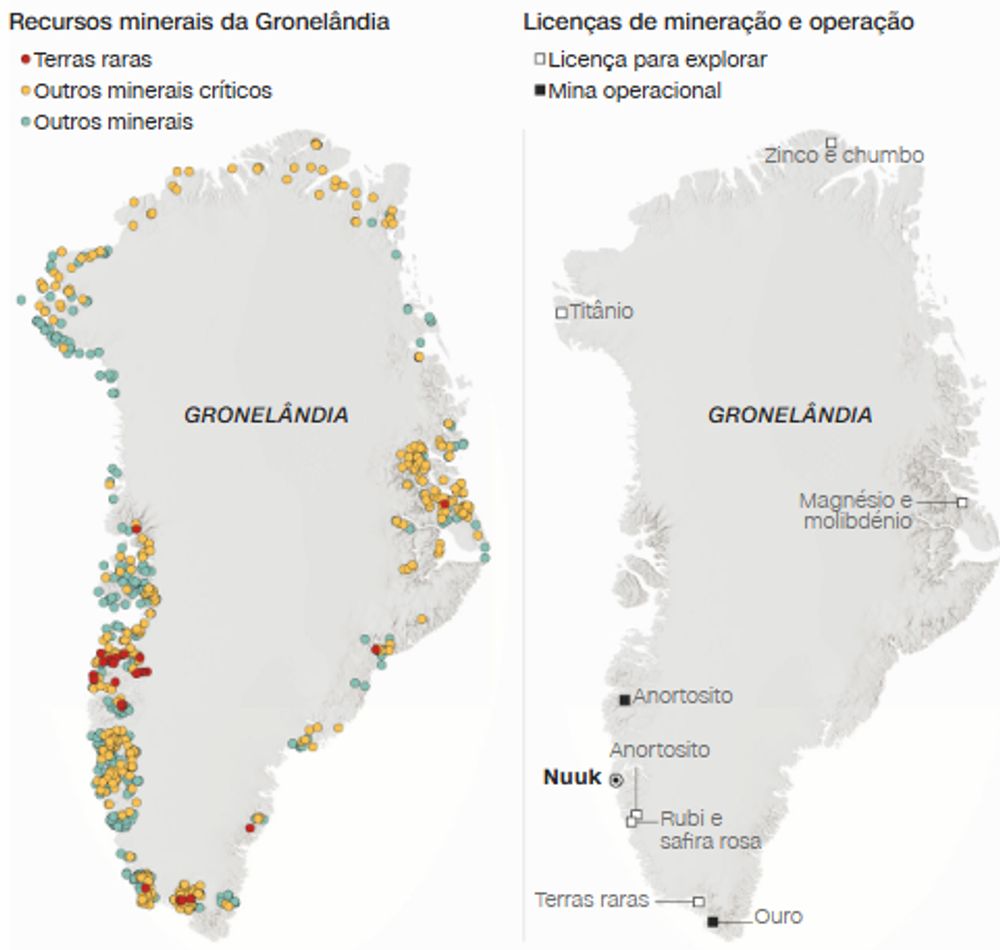

Greenland’s untapped mineral wealth

Greenland has more than 1,100 identified mineral sites, but there are only two active mines and only eight active mining licenses. More than 600 sites contain minerals designated by the US as essential to its economy and national security.

Last updated: January 7, 2025.

Note: the occurrence of minerals does not indicate the economic viability of extraction. There are 60 “critical minerals” defined by the US government, 15 of which are rare earth elements. The data only shows the primary resource at each location.

Fontes: National Geological Surveys for Denmark and Greenland, Greenland’s Mineral Licence and Safety Authority, The US Department of Energy, US Geological Survey, Greenland Business Association

Graphic: Soph Warnes, CNN

With regard to mining exploration, there is a possibility that melting ice will expose land that was previously impossible to explore. According to the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Greenland in particular could be a hot spot for coal, copper, gold, rare earth elements and zinc.

However, researchers say it would be extremely difficult and expensive to extract Greenland’s minerals because many of the island’s mineral deposits are found in remote areas above the Arctic Circle, where there is a kilometer-thick polar ice sheet and where darkness reigns for much of the year.

The idea that these resources could be easily extracted to the benefit of the US was described to CNN as “completely crazy” by Malte Humpert, founder and senior fellow at The Arctic Institute.

While Trump has recently focused on the security aspects of Greenland, his former national security adviser Mike Waltz told Fox News in 2024 that the administration’s focus in Greenland was “on critical minerals” and “natural resources.”

CNN’s Lou Robinson, Nick Paton Walsh, Natalie Wright, Matt Egan and Laura Paddison contributed to this report