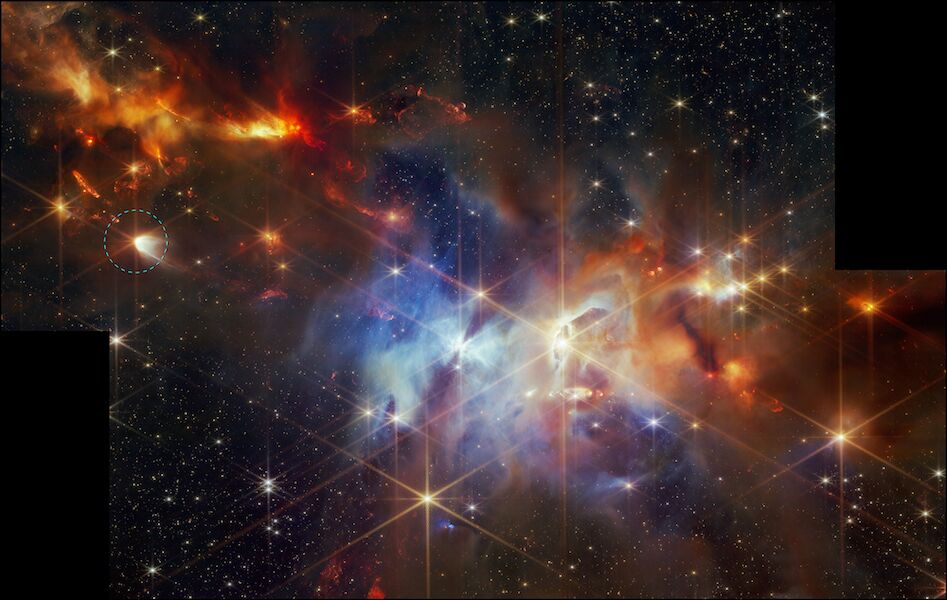

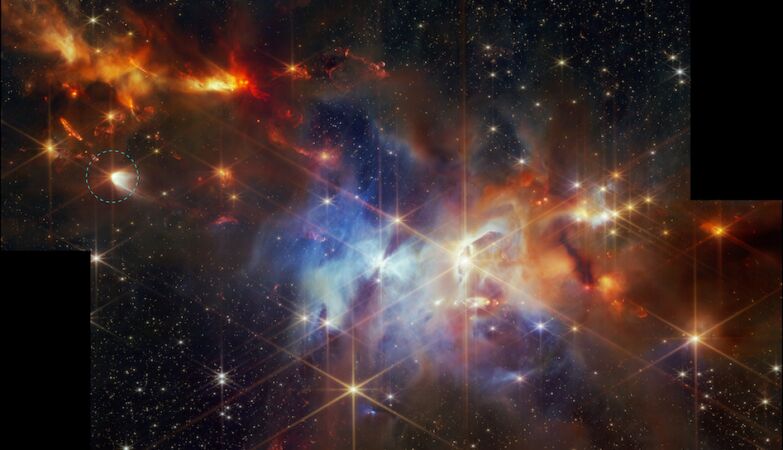

NIRCam image from 2024, from the James Webb Space Telescope, showing the protostar EC 53 in the circle on the left. Researchers using Webb’s new MIRI data have proven that crystalline silicates form in the hottest part of the disk of gas and dust surrounding the star – and can be shot out to the edges of the system.

Somewhere in the Serpent Nebula, Webb showed how the disk of gas and dust surrounding a very young, actively forming star is where crystalline silicates are forged and how crystals are transported.

Astronomers have long sought evidence to explain why comets on the outskirts of our Solar System contain crystalline silicatessince crystals require intense heat to form and these “dirty snowballs” spend most of their time in the ultracold Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud.

Now, looking beyond our Solar System, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has presented the first conclusive evidence linking how these conditions are possible.

The telescope clearly showed, for the first time, that the hot, inner part of the disk of gas and dust surrounding a very young, actively forming star is where crystalline silicates are forged.

Webb also revealed a strong flow that is capable of transport the crystals to the outer edges of this disc. Compared to our Solar System, which is completely formed and mostly clean of dust, crystals would be forming roughly between the Sun and Earth.

Sensitive observations of the protostar, by Webb in the mid-infrared, star is cataloged EC 53also show that powerful winds from the star’s disk are likely catapulting these crystals to distant locations, such as the incredibly cold edge of its protoplanetary disk, where comets may eventually form.

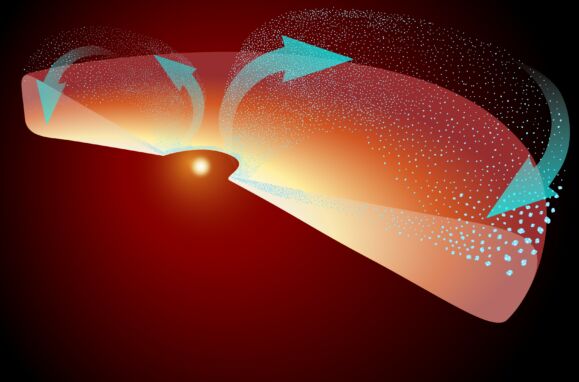

“The structured flows of EC 53 can lift these newly formed crystalline silicates and transfer them to the outside, as if they were in a cosmic highway“, said Jeong-Eun Lee, the lead author of a new scientific article in the journal Nature and a professor at Seoul National University in South Korea.

“Webb not only showed us exactly what types of silicates are found in the dust near the star, but also where they are found before and during a flare.”

The team used the MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) of Webb to collect two sets of highly detailed spectra to identify specific elements and molecules and determine their structures. They then precisely mapped where everything is, both when EC 53 is “calm” (but still gradually “nibbling” at its disk) and when it is most active (what is known as an eruptive phase).

This star, which has been studied by this team and others for decades, is highly predictable (Other young stars have erratic flares, or their flares last hundreds of years). Every 18 months, EC 53 begins a bombastic 100-day eruptive phase, accelerating the pace and absolutely devouring gas and dust from the surrounding area, while ejecting part of what it ingests in the form of powerful jets and streams. These expulsions can throw some of the newly formed crystals to the outskirts of the star’s protoplanetary disk.

“Even as a scientist, it is amazing to me that we can find specific silicates in space, including forsterite and enstatite near EC 53,” said Doug Johnstone, co-author and principal investigator at the NRC (National Research Council) in Canada. “These are common minerals on Earth. The main ingredient on our planet is silicate.”

For decades, research has also identified crystalline silicates not only in comets in our Solar System, but also in distant protoplanetary disks around other, slightly older stars, but has been unable to determine how they got there. With Webb’s new data, researchers now better understand how these conditions are possible.

“It’s incredibly impressive that Webb can not only show us so much, but also where everything is,” he said. Joel Greenco-author and instrument scientist at STScI (Space Telescope Science Institute) in Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

“Our research team has mapped how crystals move throughout the system. We have effectively shown how the star creates and distributes these superfine particles, which are significantly smaller than a grain of sand“.

Webb’s MIRI data also clearly shows the star’s narrow, high-speed jets of hot gas near its poles, and the slightly cooler, slower outflows that come from the inner, hotter area of the disk that feeds the star.

Illustration represents half of the disk of gas and dust surrounding the protostar EC 53. Stellar flares periodically form crystalline silicates, which are thrown upward and outward from the system’s boundaries, where comets and other icy rocky bodies can eventually form.

The image above, obtained by another Webb instrument, NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera), shows a set of winds and scattered light from the EC 53 disk, inside a white circle, tilted to the right. Its winds also flow in the opposite direction, approximately behind the star, but in the near infrared this region appears dark. Its jets are too small to be detected.

Looking ahead

EC 53 is still “wrapped” in dust and could continue to be for another 100,000 years. Over millions of years, as the disk of a young star is heavily populated with small dust grains and pebbles, a incalculable number of collisions which can slowly build a series of larger rocks, eventually leading to the formation of terrestrial planets and gas giants.

As the disk settles, both the star and the rocky planets finish their formation, the dust disappears (no longer obscuring the view) and a Sun-like star remains at the center of a clean planetary system, with crystalline silicates “scattered” throughout.

EC 53 is part of the Serpent Nebula, which is located 1300 light-years from Earth and is full of actively forming stars.