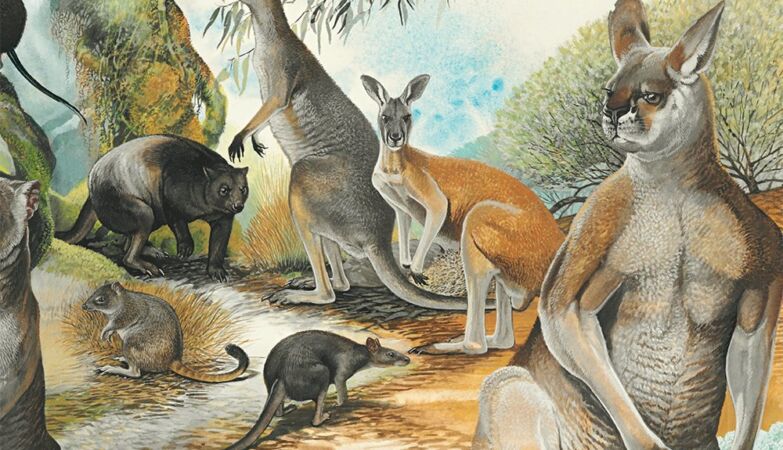

Peter Schouten

Procoptodon goliah (right) and other extinct macropods, by Australian artist and illustrator Peter Schouten

In a new study of the fossil remains of giant prehistoric kangaroos, scientists have found that these animals, weighing more than 200 kg, weren’t too big to jump — just that they probably didn’t jump as far as today’s marsupials.

Kangaroos have probably been bouncing around the planet for much longer than experts previously believed.

A new one, published this Thursday in the magazine Scientific Reportssuggests that the ancestors of today’s marsupials jumped — despite growing much larger than their descendants who are hopping around Australia today.

For thousands of years, the biggest jumping animal on the planet has been the Australian red kangaroo (Osphranter rufus). A male easily reaches more than one and a half meters in height, weighs 90 kilos and moves about 60 km/h at a rate of up to two meters per jump.

But as big as they are today, their evolutionary relatives were even bigger. During the Ice Age, there are about 45,000 yearsthe giant kangaroos of the subfamily Sthenurinae They often grew to more than twice the size of today’s marsupials. Paleontologists estimate that the largest, Procoptodon goliathhe had two meters tall and weighed more than 250 kiloss.

It is easy to assume that the P. goliath and other giant kangaroos lost the ability to jump as a result of all this body mass. According to currently accepted estimates, increasing the scale of a red kangaroo’s anatomy would make the physical act of jumping mechanically impossible above 150 kilos.

But second Megan Jonesevolutionary scientist at the University of Manchester and first author of the study, this has been the problem.

“Previous estimates were based simply increasing the scale of modern kangaroos, which could mean we miss crucial anatomical differences,” says Jones in one from the University of Manchester.

“Our findings show that these animals were not just larger versions of today’s kangaroos, were built differentlyin ways that helped manage its enormous size“, details the researcher.

In the study, Jones and colleagues present arguments for a new perspective on giant kangaroos from the Ice Age. Their conclusions result from a comparison between the skeletal anatomy of current kangaroos and the fossils of their marsupial cousins.

The team focused specifically on dtwo primary limitations for jumping: the resistance of the bones of the foot and the way in which the ankle could support tendons strong enough to facilitate locomotion.

Unlike today’s kangaroos, megafauna Sthenurinae had foot bones thicker and shorter and wider heels. This combination probably allowed them deal with intense downward force of jumping with the help of powerful tendons. At the same time, giant kangaroos probably they weren’t constantly jumping around through ancient Australian landscapes.

“Thicker tendons are saferbut they store less elastic energy”, explains Katrina Jonesbiologist at the University of Bristol and co-author of the study.

“This probably made giant kangaroos jumpers slower and less efficient, best suited to short bursts of movement instead of long-distance travel”, concludes the researcher.

The study authors conclude, the intermittent leaps of giant Ice Age kangaroos were not simply impressive displays of talent; were used for cross difficult terrain more easily, or escape imminent danger from predators.