It is the story of how the citizens of the GDR managed to overthrow this border with a peaceful revolution, without firing a single shot.

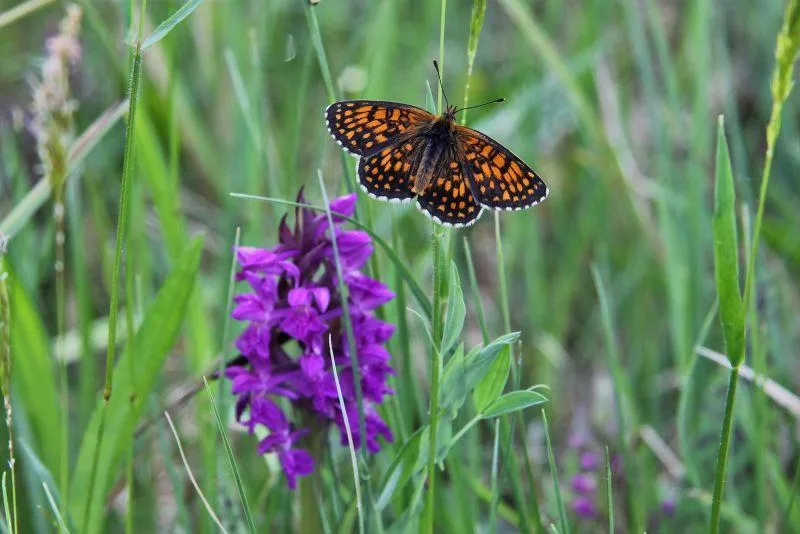

(Photo above: Once one of the most dangerous places in Europe, Cheiner Torfmoor is now a haven for wildlife. Helmac/Ute Machel/BUND Sachsen-Anhalt)

Germany’s most serene landscape owes its existence to one of its fiercest paranoia.

O Green ribbon — the Green Belt that stretches 1,380 kilometers along the former border between communist West Germany and East Germany — is today a vast area of orchids, wetlands and bird-rich heathlands.

It began as a fortified no man’s land, littered with landmines, and patrolled day and night to prevent Eastern citizens from escaping.

Anyone who visits this place today feels the Cold War as something almost impossible. You can hear birdsong and frogs croaking as a wooden walkway crosses Cheiner Torfmoor marsh, where orchids bloom.

But this tranquility only exists because, in the past, people were forced to stay away.

Today, in the northern regions of Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt, roughly between Hamburg and Berlin, the Cheiner Torfmoor, or Chein marsh, is one of the country’s most famous wetlands.

In spring and summer, it transforms into a mosaic of moors, wetlands and bog forests, full of birds and frogs. In March and April, the moor fills with color with the flowering of around 6,000 orchids, including the rare violet orchid. A walkway allows visitors to explore the site without damaging the flowers or the fertile soil beneath.

The origins of this pristine biosphere date back to the Cold War. Between 1949 and 1989, he was part of the so-called Inner German borderor Inner German border — the line that separated West Germany from the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) to the east.

On the GDR side, it was a place surrounded by barbed wire, minefields, surveillance towers and automatic firing devices — not to ward off invaders, but to prevent citizens from escaping. About five kilometers long, the GDR’s militarized restriction zone, known as exclusion zoneextended along the Inner German border and was patrolled 24 hours a day.

The former border now constitutes a wildlife refuge nearly 1,400 kilometers long (Image BROKER.com/Alamy Stock Photo)

The regime called it Antifaschistischer Schutzwall (Anti-Fascist Protective Barrier), but its true objective was clear: to prevent GDR citizens from leaving the country.

In addition to the central lane, the exterior accesses of the exclusion zone they were uninhabited and without civil activity, creating a no man’s land that, unintentionally, became a nature reserve.

Approaching the border with binoculars was prohibited. Still, despite the risks, the area quickly attracted the attention of birdwatchers on both sides of the border.

“We discovered that more than 90% of the rare or seriously endangered birds in Bavaria — such as the Northern Warbler, the Great Blue and the European Nightjar — could be found in the Green Belt,” says Kai Frobel, born in 1959 in Hassenberg, around 200 miles south of Cheiner Torfmoor. “This space became the final refuge for many species and remains so today.”

Frobel is currently a professor of Environmental Ecology, but growing up near the border, he was an avid bird watcher during the years when the exclusion zone still existed.

From a nature conservation perspective, the Iron Curtain was a blessing: an accidental wildlife sanctuary for 40 years. So it was no surprise when, in December 1989, a month after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Frobel organized a meeting in Hof, another border town south of Cheiner Torfmoor, to discuss the future of this accidental nature reserve.

Four hundred conservationists from both sides of the border were present. It was there that the name and concept of Cinturão Verde was born. Participants unanimously approved a resolution to protect it under the umbrella of the German Federation for the Environment and Nature Conservation, also known as BUND. (Frobel would later become spokesperson for the Green Belt project in the Bavarian branch.)

From “death strip” to nature reserve

The former no man’s land, now known as the Green Belt, is now a protected space, but continues to face threats (Helmac/Ute Machel/BUND Saxony-Anhalt)

The first step towards preservation was determining what there was to protect. A formal study of ecosystems and species along the Green Belt was quickly initiated, conducted by ornithologists, botanists and entomologists on behalf of BUND. In 2001, the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation called for the creation of formal nature reserves in as many areas as possible, with the aim of establishing a system of ecological interconnection at a national level. However, the newly reunified government chose to return the land to the former owners.

Resistance ended in 2002, when neither more nor less than Mikhail Gorbachev, the last president of the USSR, supported the initiative by becoming the first person to buy a “Green Belt share”, a promotional initiative created by BUND. Their support generated greater public support.

In 2005, German Chancellor Angela Merkel designated the Green Belt as part of Germany’s National Natural Heritage. This decision ensured that lands still owned by the German government along the Green Belt would be transferred free of charge to the various regional states as nature reserves, realizing the vision that Frobel and his colleagues had endorsed 16 years earlier. In 2017, Frobel and the then president of the Union for Nature Conservation, Hubert Weiger, received the German Environment Prize, Europe’s most prestigious environmental award, in recognition of their activism.

Currently, the Green Belt covers the entire former border area and runs through six German states. It connects wetlands, forests, grasslands and river floodplains, and is home to more than 1,200 rare or endangered species — the most extensive biotope network in Germany. In 2024, it was submitted for consideration by UNESCO for inclusion on the World Heritage list.

“We must tell why there is no longer a border there”, emphasizes Olaf Zimmermann, executive director of the German Cultural Council, who played a decisive role in its inclusion on the German list of proposed UNESCO sites. It is the story of how the citizens of the GDR managed to overthrow this border with a peaceful revolution, without firing a single shot.

From Germany and beyond

Natural areas can act as a line of defense, as happens on the border of Poland and Lithuania with the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad (Sergei because/AFP/GETTY MEMBERS)

Unfortunately, this fascinating story does not mean that the Green Belt will be safe forever. Although a large part of the area is protected, politicians can still redefine its use — as happened in the state of Hesse, in 2024, when the local government reduced the area allocated to the nature reserve, following protests from local communities and hunting and agricultural associations.

For more than a decade, BUND has collaborated with environmentalists and volunteer groups across Europe to expand the Green Belt beyond Germany, creating a network of biospheres stretching nearly 12,800 kilometers from the Barents Sea to the Adriatic and the Black Sea, following the former Cold War borders of 24 states.

Other ancient borders show the relevance of this idea. More than 100 rare species, including the musk deer and the Asian black bear, have found refuge in the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. The rare Cyprus mouflon and curlew thrive in the UN-established 180-kilometer buffer zone that divides the island of Cyprus.

There is another increasingly compelling reason to turn border areas into nature reserves: defense.

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, European Union countries bordering Russia and Belarus erected border fences and fortifications, while the Baltic States began planning a “Baltic Defense Line” with bunkers and anti-tank ditches, taking advantage of natural defenses such as ponds and rivers. Many Baltic experts also advocate the restoration of peatlands.

Rewilding doesn’t just offer a defensive advantage; Wetland restoration can revitalize biodiversity, provide shelter for endangered animals, absorb flood waters and capture CO₂. On the other hand, drained swamps release carbon and contribute to global warming.

“Biodiversity allows nature to produce more adaptations to changing conditions”, points out Katrin Evers, biodiversity project manager at BUND. “Intact forests or heathlands retain water in the region and can therefore protect against both floods and droughts. They also filter water and provide shade, ensuring a certain degree of climate resilience.”

Back in Cheiner Torfmoor, a former GDR watchtower, boarded up and covered in graffiti, still stands among the orchids — a sign that the Green Belt remains a living memorial to Germany’s painful division and peaceful reunification. The Green Belt is, at the same time, a landscape of memory and an extraordinary network of ecosystems. It is an environment that directly links nature to history — and where a border erected by fear can, nevertheless, serve as a model of resilience.