Andy Biggin / University of Liverpool

Although we have sent probes billions of kilometers into interstellar space, humans have barely scratched the surface of our own planet, not even making it through the thin crust.

Information about the Earth’s deep interior comes mainly from geophysics and is very valuable. We know that it consists of a solid crustin a rocky mantle, in a liquid outer core and in a solid inner core.

But what exactly is going on At each layer, and between them, it is a mystery.

Now, a study led by geomagnetism professor Andrew Bigginfrom the University of Liverpool, used our planet’s magnetism to shed light on the most significant interface within the Earth: the boundary between core and mantle.

About 3,000 km under our feets, the Earth’s outer core, an unimaginably deep ocean of molten iron alloy, churns incessantly to produce a global magnetic field that extends far into space.

Support this “geodynamo“, and the planetary force field that has produced over the last billion years, protecting Earth from harmful radiation, requires a lot of energyexplains Biggin in an article on .

This was supplied to the core in the form of heat during the formation of the Earth. But is only released to activate the geodynamo as it propagates outward toward the colder solid rock floating above in the mantle.

Without this massive heat transfer From the core to the mantle and ultimately through the crust to the surface, Earth would be like our closest neighbors, Mars and Venus: magnetically dead.

Bubbles enter

Geophysical maps show the speed at which seismic waves passing through Earth’s rocky mantle change in its lower partjust above the nucleus.

Particularly notable are two vast regions close to the equatorbeneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean, where seismic waves travel more slowly than elsewhere.

What makes these speciallarge basal structures of the lower mantle”or “bubbles” for short, is unclear. They are made of solid rock similar to the surrounding mantle, but may have a higher temperatureor a different composition, or both.

It would be expected that strong temperature variations at the base of the mantle would affect the underlying liquid core and the magnetic field that is generated there. The solid mantle changes temperature and flows at an exceptionally slow rate (millimeters per year), so any magnetic signature from strong temperature contrasts should persist for millions of years.

From rocks to supercomputers

Biggin’s study, presented in a published Tuesday in the journal Nature Geosciencepresents new evidence that these bubbles are hotter than the surrounding lower mantle. And this had a notable effect in the Earth’s magnetic field over at least the last few hundred million years.

As igneous rocks, recently solidified from molten magma, cool at the Earth’s surface in the presence of its magnetic field, acquire permanent magnetism that is aligned with the direction of this field at this time and place.

It is already well known that this direction changes with latitude. The study authors noted, however, that magnetic directions recorded by rocks up to 250 million years old also seemed to depend on location where the rocks had formed in longitude.

The effect was particularly notable at low latitudes. Therefore, researchers wondered whether bubbles could be responsible.

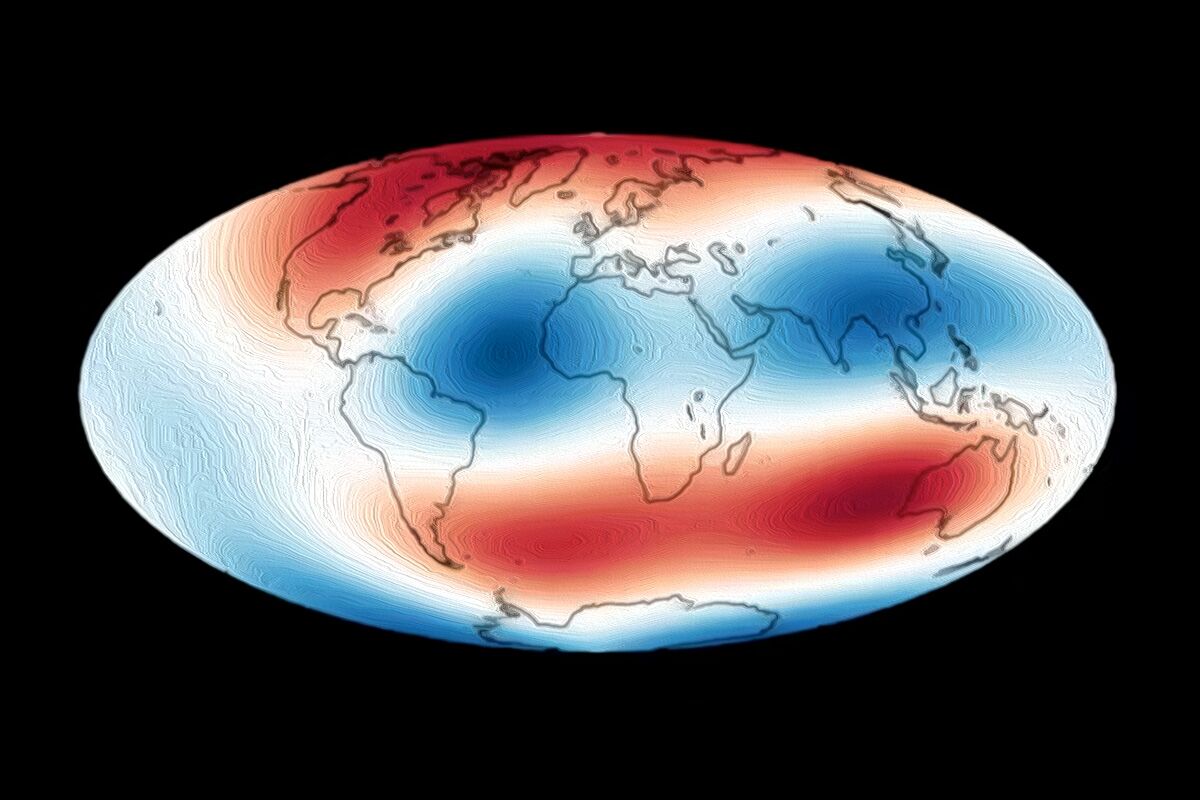

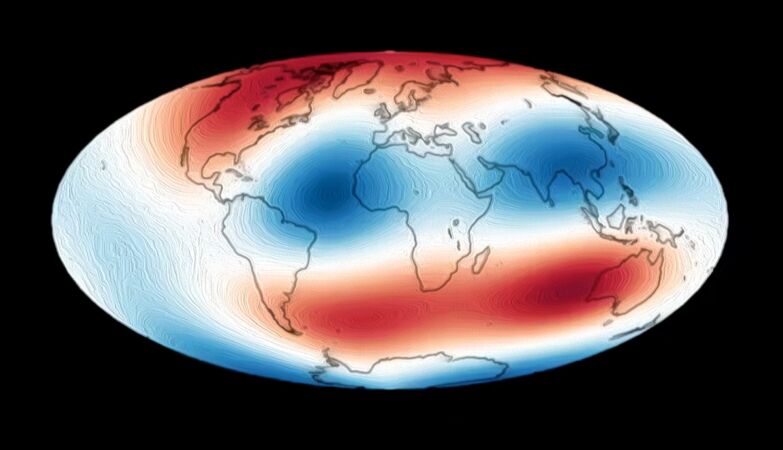

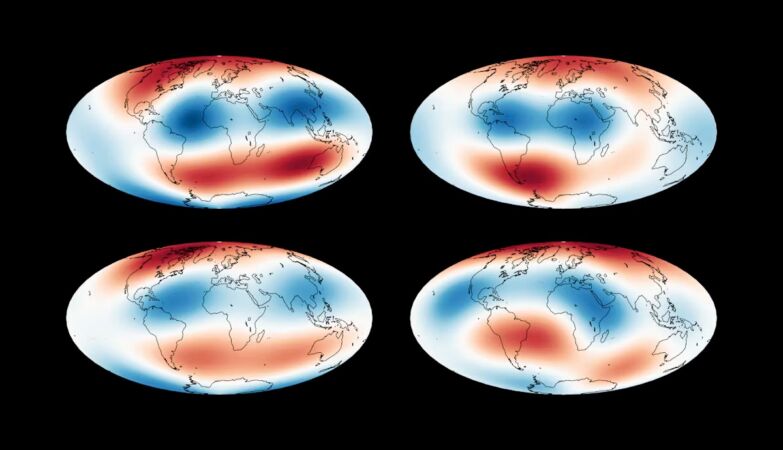

Andy Biggin / University of Liverpool

Simulated maps of the Earth’s magnetic field (left) can only resemble those of the real field (right) if the Earth’s core is considered to have clumps of hot rock positioned directly above it

A litmus test came from comparing these magnetic observations with geodynamo simulations run on a supercomputer.

As the study authors concluded, what appears to be happening is that the two hot bubbles are isolating the liquid metal beneath thempreventing heat loss that would otherwise cause the fluid to thermally contract and sink into the core.

Since it is the flow of fluid from the core that generates more magnetic fieldo, these stagnant ponds of metal do not participate in the geodynamo process.

Furthermore, in the same way that a cell phone can lose signal when placed inside a metal case, these stationary areas of conductive liquid act to “shield” the magnetic field generated by the circulating liquid below.

The huge bubbles therefore gave rise to characteristic patterns of longitudinal variation in the shape and variability of the Earth’s magnetic field. And this corresponded to what was recorded by rocks formed at low latitudes.

Most of the time, the shape of Earth’s magnetic field is similar to what it would be produced by a bar magnet aligned with the axis of rotation of the planet. This is what causes a magnetic compass to point nearly due north in most places on the Earth’s surface, most of the time.

Collapses into weak and multipolar states have occurred many times throughout geological history, but are quite rare and the field appears to have recovered relatively quickly afterwards. In simulations, at least, bubbles seem to help make this happen.

Although we still have a lot to learn about what are bubbles and how they originated, it may be that, by helping to keep the magnetic field stable and useful to humanity, we have much to thank them for.