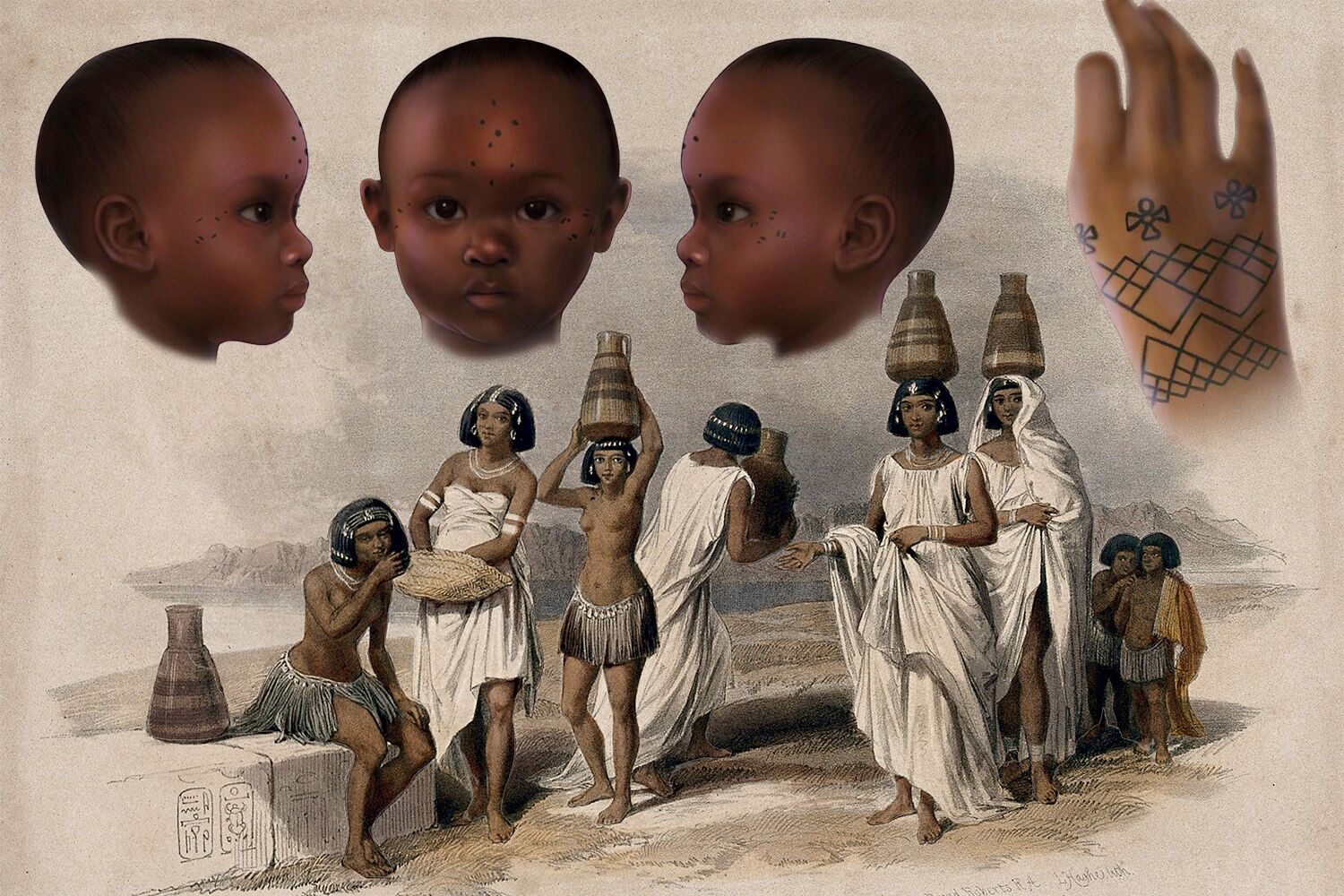

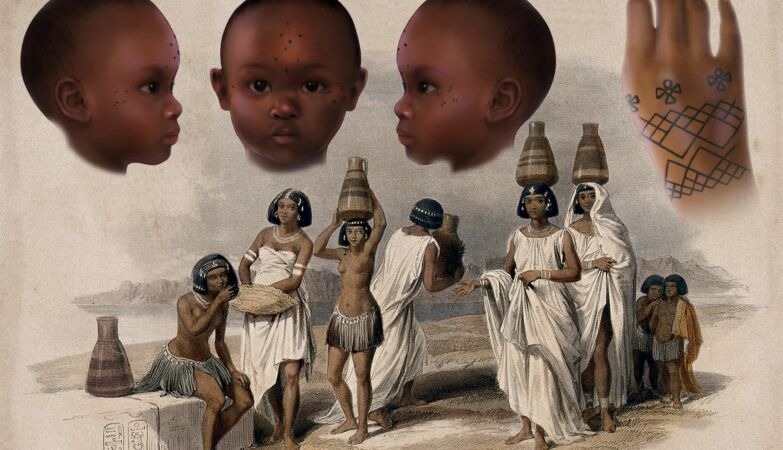

ZAP // Mary Nguyen / UMSL; Wellcome Trust / Wikipedia

Reconstruction of the tattoo on the forehead and hand of a 3-year-old girl (657–855 AD) from Kulubnart. In the background, a group of Nubian women and children resting on the banks of the Nile in Korti, Sudan

Tattoos on children in ancient Nubia challenge ideas about belief, care and the body. The practice may be related to the community’s faith, and be a way for parents to permanently mark their children as Christians.

Along the Nile in what is now Sudan, archaeologists have discovered evidence that there are more than 1,400 the children, some barely past infancy, were tattooed. Surprisingly, the discovery resulted from human remains found years ago.

In a new study, a team of researchers used infrared light to look beneath the surface of preserved skin, and found tattoos that had past unnoticed for decades.

The results of the study, presented in a recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that tattooing in ancient Nubia was much more common than previously thought and that it played a relevant role in childhood, faith and health.

The study was based on a systematic survey of 1,048 individualsdated between 350 BC and 1400 AD, of which 27 had clear tattoosnearly doubling the number previously documented in the ancient Nile Valley.

The mortal remains analyzed come from three archaeological sitess: Semna South, Qinifab and Kulubnarti. Everyone was excavated in the 1960s and 1970s and later deposited at Arizona State University.

Although they have been studied for years, many tattoos were simply too tenuous to be seen with the naked eye.

“I have known for a long time that there were tattoos in the Semna South collection,” he explained. Brenda Bakerbioarchaeologist at Arizona State University and co-author of the study, at . “I always wanted to do a much more systematic survey because many of them are not visible to the naked eye.”

Everything changed when the anthropologist Anne Austinfrom the University of Missouri–St. Louis and lead author of the study, introduced multispectral imaging in the project.

Near-infrared light allows scientists to look just below the surface of the skin. Through the lens, the paint literally emerges from the darkness, and with the support of PhD researcher Tatiana Jovanovicthe team identified 25 tattooed individuals who were previously unknown.

In Kulubnarti, a medieval Christian community, the results were impressive. At least 19% of the population had tattoos.

The most surprising thing was the discovery of paint in children less than three years old. One of them presented tattoos superimposed on older onessuggesting that it was marked repeatedly in its early years of life.

Faith, Healing and Childhood

Why would a child be so young? The answer is not entirely clear, but it must be related to the faith of the community.

In Kulubnarti, a settlement that was active between 650 and 1000 AD, the Christianity was the foundation of society. Many tattoos featured dots and lines in a diamond pattern – likely representations of the cross.

“If tattoos were a symbol of the bearer’s Christian faithmay have been important for parents create permanent ways to mark your children as Christians,” explains Austin.

These brands could function in a similar way to baptism. Therefore, they may represent the oldest evidence of Christian tattoo traditions in northeast Africa, possibly linked to practices still existing in the region today.

However, the paint may have had a most practical and urgent purpose: healing. Investigators also found tattoos overlapping older ones, even on young children. This pattern points to repetition.

“We found overlaying new tattoos about old tattoos,” Baker explained. “This may be due to illnesses – something like malaria, which causes recurring fevers and headaches.”

Malaria has a long history in the Nile Valley and there are ethnographic records elsewhere that associate tattooing with protection or healing. In two adults, tattoos were found on the back, a location that, in other contexts, is linked to therapeutic practices.

The tattoos appear to have been made with small blades instead of needles, producing simple drawings quickly. Austin warned of the danger of judging this practice by current standards. “The tattoo in Kulubnarti seems no more extreme than piercing a small child’s ears”, he said.

Tattooing is an ancient practice, observed even in Egyptian mummies. What distinguishes Nubia is the fact that the tattoos are made on children, indicating how the belief, health and body they were deeply connected from the first years of life.