The government does not hesitate to often publish densely produced with , adopting cartoonish graphics and , even promoting them through its official social media accounts and the internet.

However, the White House’s use of artificial intelligence has begun to worry disinformation experts, who fear that the spread of manufactured or edited images is eroding the public’s perception of what is ultimately true and fostering mistrust of information in general.

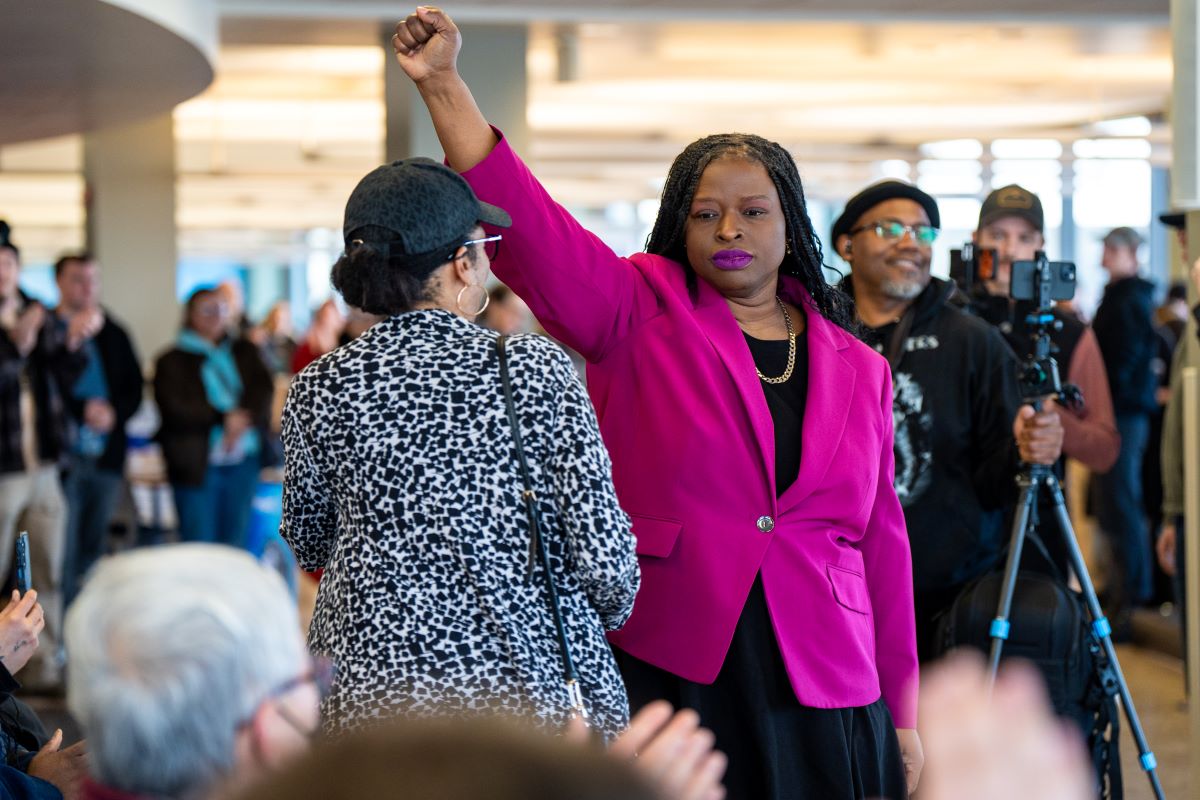

The case of Nekima Armstrong’s photograph

A typical example of how the Trump administration chooses to blur the lines between truth and falsehood, or rather between reality and its falsification, is the edited – and realistic – image of civil rights lawyer Nekima Levi Armstrong crying after her arrest.

The regular, authentic photo from the lawyer’s arrest first appeared on Homeland Security Secretary Christy Noem’s account, but shortly after, the official White House account chose to post an altered version of the photo showing Noem crying, implying that she’s not so tough on “the law” after her arrest.

This falsified image is part of a “river” of AI-altered material circulating across the political spectrum following the murders of Renee Goode and Alex Pretty by ICE and Border Patrol agents in Minneapolis, with the primary goal of disorienting those incidents.

Trump’s associates are indifferent to criticism

Despite heavy criticism of Trump’s staff for using fake images like Armstrong’s, communications officials appear to be adopting an “Internet troll” attitude, defending the related posts and saying they won’t stop the memes.

David Rudd, a professor of information science at Cornell University, told the Associated Press that labeling the altered image as a meme “is clearly an attempt to present it as funny or humorous content, similar to more cartoonish posts.” This, he said, is likely to protect the White House from criticism for publishing false material. He added that the purpose of sharing this particular image from the lawyer’s arrest is “much more unclear” than that of previously published cartoon images.

No more “reliable” information from the government

Memes have always conveyed layered messages that are funny or informative to those who understand them, but incomprehensible to the rest. Images that have been enhanced or edited with artificial intelligence are just the latest tool for the White House to reach the part of Trump’s base that spends a lot of time online, said Zach Henry, a Republican communications consultant and founder of the influencer marketing firm Total Virality. “Those who are constantly online will see this and immediately recognize it as a meme,” he said. “Your grandparents might see it and not understand it, but because it looks real, their kids or grandkids will ask.”

The creation and dissemination of distorted images, especially when they come from credible sources, “perpetuates a perception of what is happening, rather than showing what is actually happening,” said Michael A. Spikes, a Northwestern University professor and media literacy researcher.

“The government should be someone you can trust for information, know that it’s accurate, because it has a responsibility to be,” he said. “By circulating and producing this kind of content, it erodes that trust — even though I’m generally wary of the term — the trust that we should have in the federal government to provide us with accurate and verified information. It’s a real loss and it worries me deeply.” Spikes noted that there are already “institutional crises” of distrust in the media and higher education, and he sees this behavior by official accounts as exacerbating the problem.

Ramesh Srinivasan, a professor at UCLA and host of the Utopias podcast, said many are now wondering where they can turn for “reliable information.” “Artificial intelligence systems will exacerbate, amplify and accelerate these problems of not trusting and even understanding what can be considered reality, truth or evidence,” he said.

Srinivasan argued that when the White House and other officials share AI-generated content, they not only encourage ordinary users to do the same, but also give permission to people with institutional power and credibility, such as congressmen and senators, to circulate material that is not flagged as fake. He added that as social media platforms tend to “algorithmically promote” extreme and conspiratorial content – which AI tools can easily generate – “we have a huge set of challenges ahead of us”.

Wave of fake videos about ICE

Social media, for example, has a wealth of AI-generated videos of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations, protests, and interactions with citizens. After Renee Goode was killed by an ICE agent while she was in her car, several AI videos of women driving away after being told to stop by police officers began to circulate. There are also many fabricated videos of ICE “raids” and of citizens confronting agents, often yelling at them or throwing food in their faces.

Jeremy Carrasco, a content creator specializing in AI viral video review and deconstruction, said most come from accounts that engage in “engagement cultivation,” seeking clicks through popular keywords such as “ICE.” But he pointed out that the videos are also being watched by people who oppose ICE and the Department of Homeland Security, who are likely watching them to “satisfy their fantasy” or “as wishful thinking,” hoping that these are real scenes of resistance.

Still, Carrasco believes most users can’t tell if what they’re seeing is fake, and wonders if they’ll be able to tell “what’s real when it’s really going to matter, when the stakes are going to be much higher.”

Even when the traces of AI are clear – such as street signs with unintelligible lettering or other obvious mistakes – only in the “best case scenario” will a viewer be suspicious or observant enough to realize that it’s AI.

Corresponding videos for Maduro – Can watermarking provide a solution?

The problem, of course, is not limited to news about immigration and protests. Fabricated and falsified images following the arrest of former Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro flooded the internet earlier this month. Experts, including Carrasco, estimate that the dissemination of AI-generated political content will become increasingly common.

Carrasco believes that the widespread introduction and use of a watermarking system, which would incorporate information about the origin of a medium and its metadata, could be a step towards a solution. Such a system has been developed by the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, but it says it is not expected to be widely adopted for at least another year.