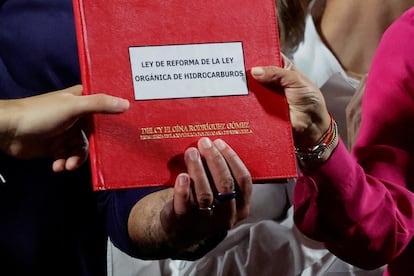

The National Assembly controlled by Chavismo has approved the reform of the oil sector and opens it to privatization. The debate on the law has been rapid, as has been demanded by the United States, which after the military attacks on January 3 in Venezuelan territory and Cilia Flores, has almost fully reestablished commercial relations with the South American country that was previously considered a focus of instability and threats for Washington.

“Today is a historic day for the Republic, because in the midst of adversity we have been able to keep our oil industry up and running,” said the head of Parliament, Jorge Rodríguez, at the end of the session. “With the maintenance of the principles of sovereignty and independence and the ownership that the Republic has of its deposits, we are going to make the sector more competitive by allowing the hiring of national and foreign companies.”

The , equalized by oil, needed this new law to give greater guarantees to the investments that President Donald Trump has said he is interested in making in Venezuela where, in addition, he seeks to displace Chavismo partners such as Russia and China.

The announcement of the approval of the reform in the Chavista Parliament has been reciprocated by the United States Department of the Treasury with the issuance of general license 46 that authorizes transactions with the government of Venezuela and with the state oil company “for the elevation, export, re-export, sale, resale, supply, storage, marketing, purchase, delivery or transportation of oil of Venezuelan origin, including the refining of said oil by an established US entity.” As a collateral measure to open the industry to American capital, this Thursday restrictions on air activity with Venezuela were also lifted and direct flights between the countries, suspended more than seven years ago, will reopen.

The previous licenses were specific with the companies that could have transactions with PDVSA, as in the case of the one that allowed the operation of the American company Chevron. This is broad in allowing operations to “established US entities.” The new license, however, indicates that transactions involving persons or entities from Russia, Iran, North Korea or Cuba are not permitted. There is no expiration date indicated but its validity depends on compliance with regular reports by companies within 10 days of the first transaction.

For its part, the new law opens the possibilities of entry for private companies through direct contracts with PDVSA. Before the reform, foreign capital could only participate in the exploitation of Venezuelan oil through the formation of mixed companies in which the Government—which during the early Chavismo promoted oil nationalism—retained the majority shareholding and operational control of the association. In this way, it responded to the Constitution that reserves oil activity and other strategic industries to the State. The creation of these mixed companies had to be approved by the National Assembly. New direct contracts with private parties only have to be notified. The new law, however, makes the reservation that the country will continue to be the owner of the deposits in which companies carry out exploitation activities.

Other specific changes are related to the marketing of crude oil. Before, only PDVSA could do it. Now, private companies can “carry out direct marketing” and manage funds in bank accounts abroad. Royalties – what those who extract oil pay to the State for the right to extract it – are capped at 30% and this percentage can be modified at the discretion of the Executive. In the first version of the reform, royalties were reduced to 20% and 15% if they were contracts or joint ventures, respectively. In addition, extensive tax exemptions have been established for those who make investments in the sector.

A clause was also included that allows for the resolution of disputes through arbitration and mediation—as previously it was only possible through Venezuelan courts without judicial independence, as is also established in the Constitution. This is a measure aimed at dispelling the fears of investors who in the past suffered losses due to expropriations applied by the Chavista Government.

The minority parliamentary opposition group had requested a broader debate on the reform that has deregulated the oil sector to favor private operations, the condition that Trump has set after the military attacks to ensure the political survival of Chavismo, which has assumed command of Venezuela without Maduro. There were only three days of public consultation in which the acting president Delcy Rodríguez met with industry workers and then with executives from oil companies interested in continuing to do business with PDVSA such as the Spanish Repsol, the American Chevron and the British Shell. In less than a month, a basic legal framework has been created for the new commercial stage between both countries. The missing approval had already been given by the Secretary of State himself, Marco Rubio, on Wednesday in his appearance before the Senate Foreign Committee. “We must give credit to the authorities. They have approved a new hydrocarbons law that basically eliminates many of the Chávez-era restrictions on private investment in the oil industry.”