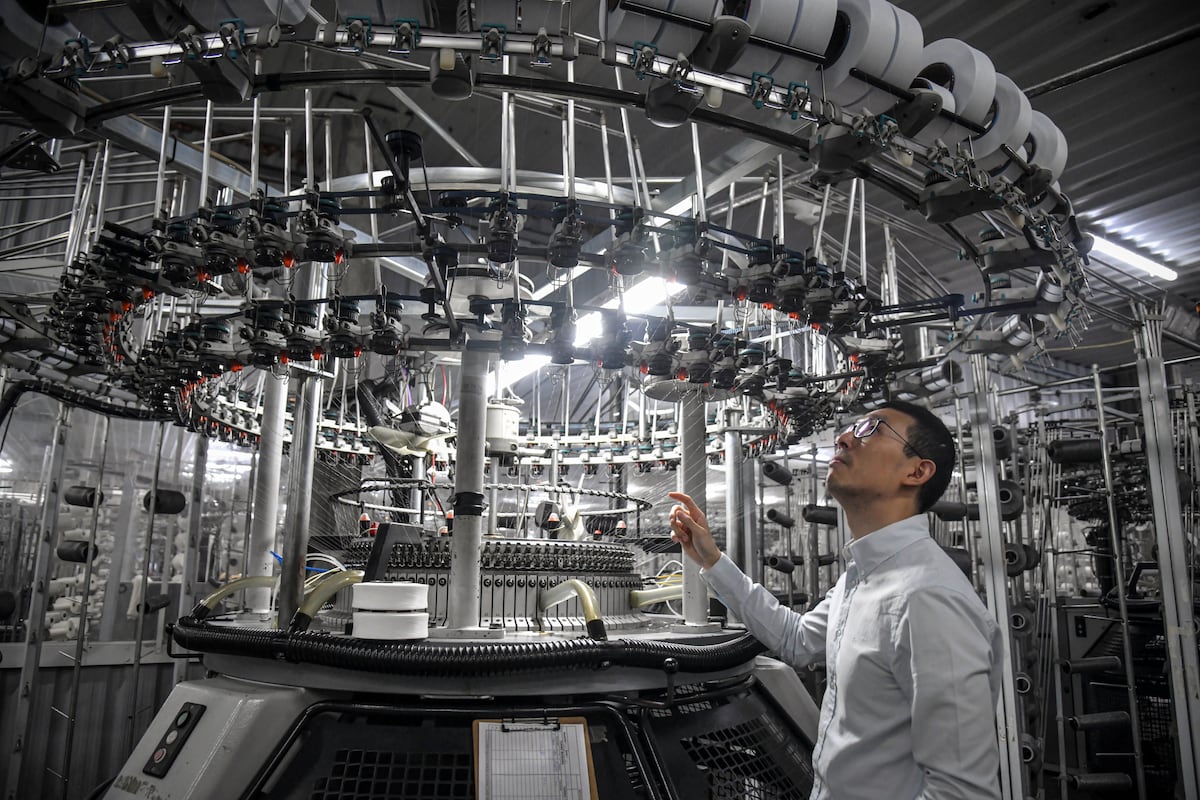

“Everyone believes that in 2001 it was , but for us this is the worst crisis we have ever experienced,” says David Kim, standing in an inert sector of his large industrial warehouse, which occupies almost three blocks in the San Martín neighborhood, on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Around him, 12 knitting machines purchased in Germany in the last five years – circular contraptions three meters in diameter and with 2,000 needles each, with the capacity to make two rolls of fabric every hour – fill with dust in complete silence. “This is the sector where we manufacture polyester fabrics, but due to imports we no longer make them,” he explains. It is Wednesday morning and in this place there is no noise or movement, neither of machines nor of people.

David Kim is 42 years old, he is the manager of the Amesud weaving factory and the son of its founder, Hong Yeal Kim, who emigrated from South Korea to Buenos Aires in 1976. This 2,700 square meter plant and enormous state-of-the-art devices is the result of a long journey that began with the small workshop that his family set up upon arriving in the country, in a marginal neighborhood known as Villa 1-11-14. Amesud has the capacity to produce 700 tons of fabric per month, but today it produces only 150: it operates at 20% of capacity. In the last two years – a period that -, the staff was reduced by 40%, going from 430 employees to 250. “And theoretically we would have to continue reducing staff, because we don’t see when this will end. Next week we are going to start with suspensions, to work only from Monday to Thursday,” says Kim.

According to the latest official record of Argentine economic activity, while sectors such as financial intermediation grow (14% in November 2025 compared to a year ago), agriculture (10.5%) and mining (7%), the manufacturing industry plummets (-8.2%). Within the industry, what falls the most is the textile sector, which on average uses only 29% of its installed capacity, something that is explained by the lower levels of production of fabrics and cotton yarns, which fell in one year by 44% and 37%, respectively.

“It is extremely harmful to the textile production system,” says Priscila Makari, economist and director of the ProTejer Foundation. “We have an artificially high exchange rate, which makes us expensive to compete, and an abrupt trade opening that led to a 71% increase in imports in 2025 compared to the previous year. This adds to a drop in demand: people have little money to consume and, on that smaller internal market, imports gain weight.” If historically the proportion was 50% national clothing and 50% imported, he details, now it is 30% national and 70% imported, without taking into account online purchases on platforms such as Shein or Temu, which have also skyrocketed recently.

Kim’s business corresponds to the second industrial link in the textile chain, in which threads are first made from natural fibers, then fabrics are made from the threads, and finally garments are made from the fabric. Amesud has around 400 clients, including international brands such as Puma, Nike or Under Armour, national brands and wholesale manufacturers without a recognized name.

“Sales dropped 60% in two years, from mid-2023,” details the businessman, who explains that his clients sell less largely due to competition with brands that make their clothes in Asian countries, where the products, in some cases, are not even aligned with international standards. “If the Government wants us to compete against Asia, at least it would have to lower our taxes. Because we compete, but the Argentine State does not compete with the Chinese State in the facilities it gives to its companies,” he says.

If the economy were ordered between winners and losers, the textile sector would be on the side of those who have fallen from grace, but for Dante Sica, director of the consulting firm Abeceb and former Minister of Production during the presidency of Mauricio Macri (2015-2019), “there are no winning and losing sectors, but rather a restructuring in the face of a change in the economic regime that seeks its new balance.” The economist considers that we are witnessing the transition from a “totally unbalanced economy, with fiscal deficit, high inflation and strong trade administration” to one “more stable, deregulated and internationally integrated, which generates more competition.” In this framework, some sectors such as agriculture, the energy ecosystem and mining gain momentum and generate investment decisions, while others such as the manufacturing industry suffer a strong impact, which is described as “an intersectoral change in income.”

“When you open up competition, you realize that the market volume is not enough to have 10 refrigerator factories or 11 car terminals in Argentina. So we are in that readjustment process. I don’t think there will be a disappearance of sectors, although obviously there will be companies that are going to fail and others that are going to lower their production level,” says Sica, and graphs: “A change of regime is like a flood: when the water goes down, you see that there are houses that survived and others that they disarmed.”

In this new context, it is desirable that companies that are no longer profitable be converted into others adapted to the demands of the new scenario. That’s what they do in the world, says Sica, but in Argentina it becomes a problem because there is no financial system to support it. Those who reconvert must do so mostly with their own resources, which determines the speed and scale of the transformation. Furthermore, the constant change in the rules of the game discourages decisions of this type, modeling a more conservative business leadership.

The discontent of textile entrepreneurs is widespread. “This is a Government that does not know about economics, but only something about finance,” one snorts, asking that his name not be used. “It is destroying the productive fabric and condemning Argentina to return to being an economy of basic products without added value, simply using the land. We will not become Norway, but Nigeria.”

However, other businessmen quietly admit that competition with Asians in the textile sector is unfeasible and that developed countries have already gone through the process of adapting, transforming national production into something smaller and more specialized. “The point is that it has to be done in a longer term, with predictability and support, not in this abrupt way,” one clarifies.

The great challenge of this new scheme is employment. The sectors that gain dynamism do not generate the same number of jobs as those that decline, nor do they demand the same capabilities, nor are they geographically located in the same place. “Those we throw out are not going to go to work at a mining company in Mendoza,” Kim says. “The majority end up unemployed or in Uber, a kiosk, a business.”

Makari specifies that the textile industry generates 540,000 jobs throughout the national territory, with provinces such as Catamarca or La Rioja, where it represents up to 40% of private industrial employment. Between December 2023 and October 2025, 18,000 formal positions were lost in the industrial links of the sector and more than 500 SMEs closed.

Is anyone going to save textiles? The Government has already warned, in private meetings with the businessmen in the sector, that it is not. And also in public. “When the economy opens, there are products that will be cheaper and jobs will be lost, but that allows individuals to spend less money,” Milei said from Davos, in an interview with Bloomberg—. In Argentina, a t-shirt cost 40 dollars; comes out five. Those 35 that a person saves will be spent in another sector,” he said.

The bet of Argentine textile entrepreneurs, then, is to resist. Downsize, burn reserves and hold on in the middle of the storm. Wait for the moment when the water recedes and find a place for them in that new landscape.