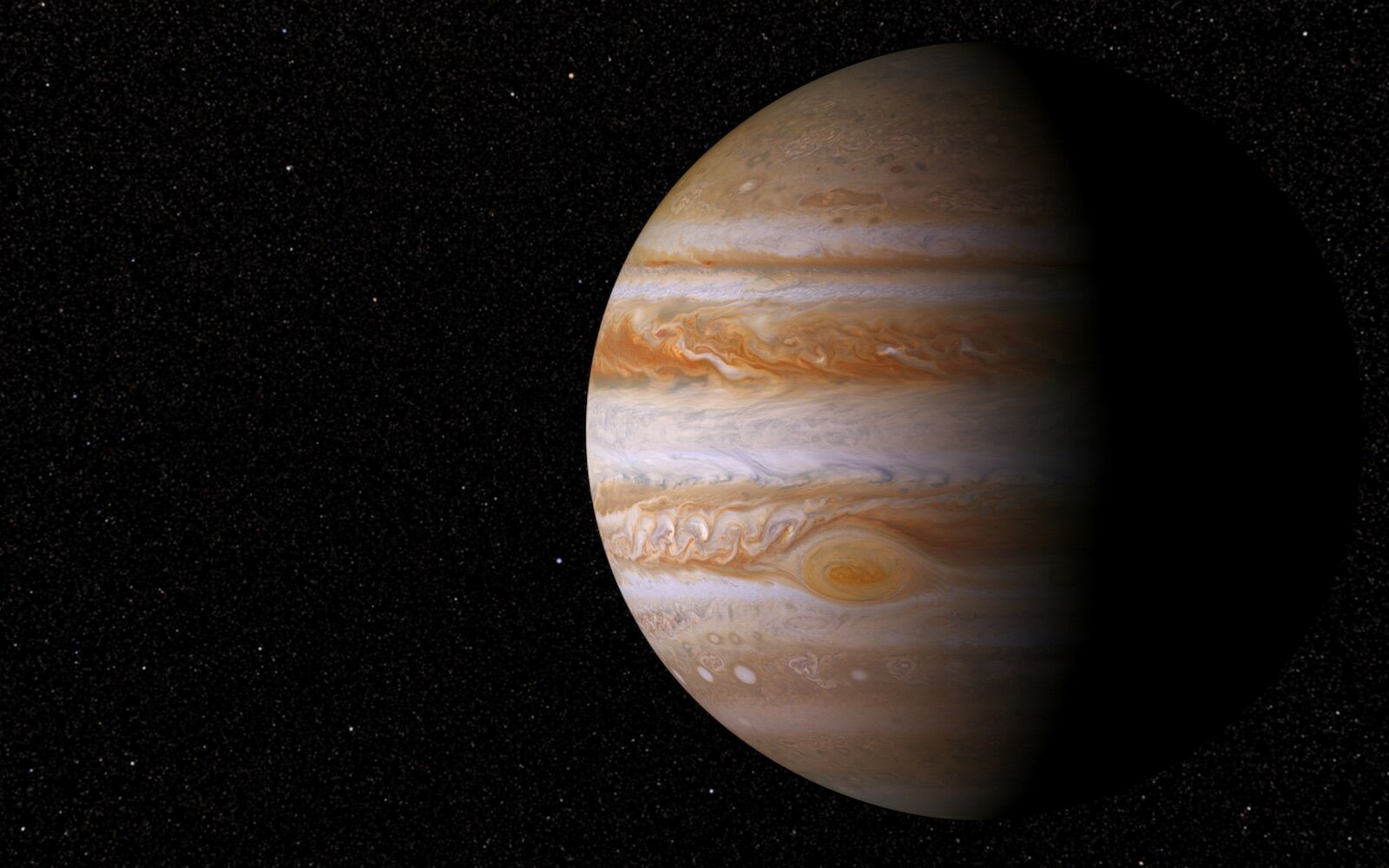

NASA SVS

Using NASA’s Juno probe, scientists were able to calculate the size of Jupiter more accurately. Its polar radius is about 12 kilometers smaller than previously thought.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, is slightly smaller and flatter than scientists believed, according to a new one published in Nature Astronomy.

Using radio data collected by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, researchers were able to calculate the dimensions of Jupiter with unprecedented precision. Although the differences from previous estimates are small and only a few kilometers, they have important implications for understanding the planet’s interior and improving models of gas giants inside and outside the solar system.

“The manuals will have to be updated,” said the study’s co-author, Yohai Kaspiplanetary scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science, in Israel. “Jupiter’s size hasn’t changed, of course, but the way we measure it has.”

For nearly 50 years, scientists have relied on measurements taken during flybys by NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 missions. These spacecraft used radio signals to estimate Jupiter’s size, and their results became the accepted standard. However, the Juno mission, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, has collected a much larger volume of radio datawhich allowed researchers to drastically improve accuracy.

The team refined Jupiter’s dimensions with a margin of error of about 400 meters in each direction. Their analysis shows that the polar radius of the planet is 66,842 kilometers, about 12 kilometers smaller than previously estimated. Jupiter’s equatorial radius was determined to be 71,488 kilometers, approximately 4 kilometers smaller than previous measurements.

To arrive at these results, scientists tracked how radio signals transmitted from Juno to Earth bent as they passed through Jupiter’s dense atmosphere, before disappearing when the planet blocked them completely. This technique allowed researchers take into account the powerful atmospheric winds that subtly distort Jupiter’s shape.

“These few kilometers make a difference,” said the study’s co-author, Eli Galantialso from the Weizmann Institute of Sciences. Small adjustments to the planet’s radius help scientists reconcile severity data with atmospheric observations, producing more accurate models of Jupiter’s internal structure.

The updated measurements are expected to improve scientists’ understanding of how Jupiter formed and evolved, as well as aid in interpreting observations of distant gas giants orbiting other stars.