“If he had missed the forecast,” said Peter Stagg from his home an hour from Bordeaux, France, “I could be sitting in German France – not in France France.” Stagg talked about the crucial role that his father, group captain James Stagg, played in the release of France from the Nazi occupation.

Father Stagg was not a general nor an infantry soldier, but at the end times before one of the most decisive moments of World War II, he was the man they all depended on.

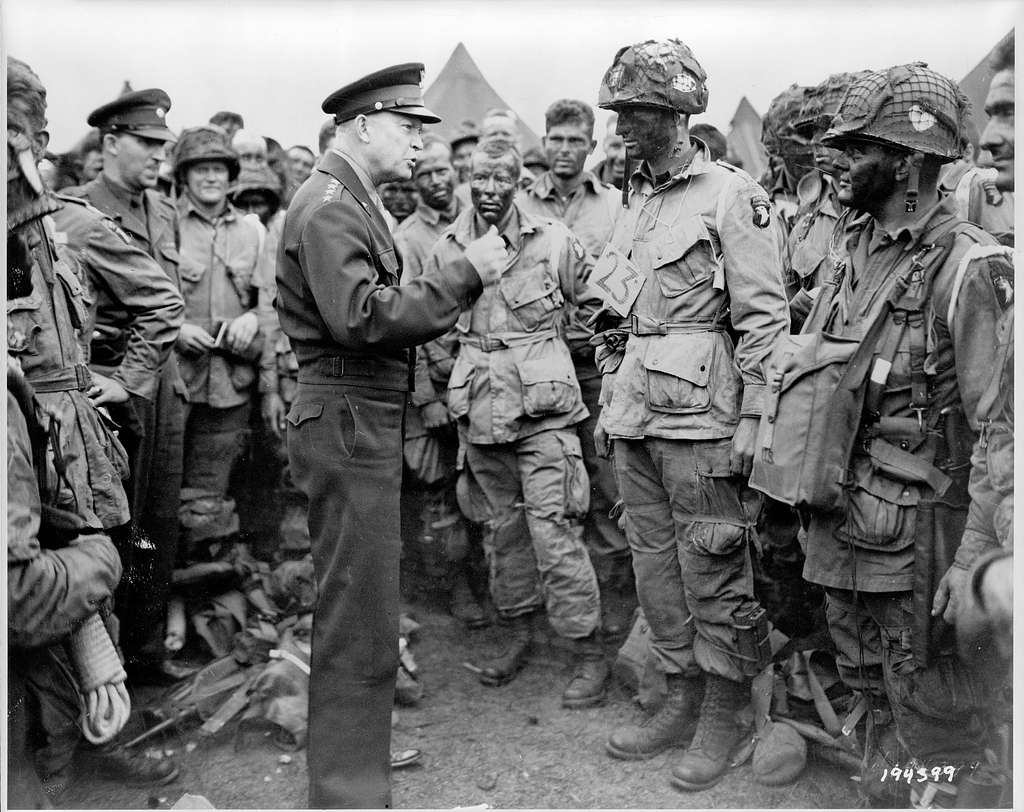

On June 6, 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered more than 150,000 allied troops to invade Normandy’s beaches on one of the largest sea invasions in history. But hours earlier, Eisenhower’s eyes were not on the battlefield, but in the sky. More precisely, in the weather forecast before him. And the meteorologist who raised her, described by her son as “a frowning and irascible Scottish,” he needed to get it right.

“The weather forecast was a yes or no,” said Catherine Ross, Met Office Library and Archives Manager, the UK meteorological service. “Everything else was ready.”

Success required a very specific set of conditions:

- Before landing, time needed to be calm for 48 hours.

- For the next three days, the wind needed to be below force 4 on the Beaufort scale, equivalent to a moderate breeze.

- For skydivers and air support, cloud coverage below 8,000 feet needed to be less than 30%, based on clouds no lower than 2,500 feet and visibility greater than 3 miles.

- A low tide was needed at dawn to expose the German defenses.

- The invasion had to occur a day before or four days after the full moon for night operations.

- In addition, the invasion needed to coincide with the east Soviet summer offensive to maximize the pressure on German forces.

The allies identified a window: between June 5 and 7. The chances were scary. According to Ross, the probability of all desired conditions align was 13 to 1 – and about three times higher by including the full moon in the equation.

Continues after advertising

To make matters worse, early June brought a very unstable period of time. “There was a succession of low pressures and fronts crossing the Channel of the Mancha, and the challenge was to find a gap,” she said. “Not just to allow the invasion, but to be able to bring sufficient troops and supplies.”

The 5th “was ideal,” Eisenhower recalled in an interview 20 years later. But the date was subject to last minute review in case of bad weather.

The man in charge of delivering this important forecast was Stagg, the main meteorological counselor of Eisenhower of the British Met Office. He was responsible for producing a unified forecast based on data from three independent groups, two British and one American.

Continues after advertising

“It was an evolutionary science.” With today’s advanced forecasts, with the help of supercomputers, satellites and sophisticated models, meteorologists can produce quite accurate predictions several days in advance. But in 1944 there was no unified approach to weather forecast.

The American team, part of the newly formed US strategic air forces near Eisenhower headquarters in southwest London, used analog forecasting, a method that compared current conditions with historical standards. British teams used hand -drawn maps, observational data, and more recent understandings of high atmosphere standards. These approaches often diverged.

“At the time, it was an evolutionary science that evolved in different ways in different countries,” said Dan Suri, a metorologist at Met Office. He stated that some of these methods are still used today, though digitally. “Aspects of what they did still appear, and the D -Day meteorologists would recognize aspects of what we did today.”

Continues after advertising

James Stagg’s work was not only scientific but diplomatic-a delicate act of balanced contrasting predictions from the American and British teams, shaping them in a narrative consistent with a decisive recommendation for Eisenhower.

“This was not always totally possible,” said Suri. “He had a very difficult job, really.”

Before the invasion, tensions increased among forecasting teams. Transcripts of daily telephone discussions between Stagg, the general and the three teams showed strong disagreements. American meteorologists believed that June 5 or 6 would have proper time. The British, however, were against the 5th.

Continues after advertising

“He had to decide which side he would be,” Ross said, “and take that to Eisenhower.”

According to Professor Julian Hunt in his book “Day D: The Role of Met Office,” a high pressure system about the Atlantic and a strong storm near the northern Scotland should cause busy seas and a lot of cloud cover on the spot canal on June 5.

James Stagg handed his decision: Strong winds would sweep Normandy, making the landing impossible.

“He gave us the worst report you’ve ever seen,” Eisenhower recalled later. Convoys who had already broken were ordered to return.

But on June 4, predictions indicated that the storm system would move to the Northeast, giving way to a brief period of calm on June 6.

Still, Stagg was uncertain. Your diary reveals your question: “I’m getting a little stunned – everything is a nightmare.”

Ross said the decision to go on was a commitment. “Was it a matter of, will day 6 be good enough? And the answer was, yes, it will be good enough. But it was a challenge.”

Eventually, American and British meteorologists arrived at a consensus for June 6. On the night of June 4, Stagg returned with the most optimistic forecast. Eisenhower described a “smile on his face.”

“We waited that with this breach, we could do that,” said Eisenhower later.

After a brief moment of reflection – “About 45 seconds,” he recalled – gave the order that would change the course of the story: “Ok, let’s go.”

The invasion took place on June 6, 1944, but the forecast was wrong. Suri said that instead of moving to the Northeast, the storm over the north of Scotland changed south, entering the North Sea and weakening. This unexpected change allowed the wind to decrease a little and visibility would improve as the front of the north of France moved away.

“That’s why things have improved,” said Suri. “So they were right for the wrong reasons.”

But the conditions remained suction cups and the hectic sea. Many of the first soldiers crossing the spot canal suffered “strong nausea,” wrote the Associated Press, and the strong winds raised white waves, making the crossing even harder.

But marginal time may have given allies a vital advantage. German predictions were similar to those of the allies, but they did not expect an invasion under such adverse conditions.

On June 4, the leading 3rd German air fleet meteorologist informed field Marshal Erwin Rommel that time on the channel would be so bad that there would be no attempts to land until June 10.

“The Germans assumed high tide, coverage of darkness and better cloud conditions, wind and visibility than the allies really needed,” said Suri.

When the allied forces attacked, the Germans were unprepared.

After the invasion, as success became clear, the full importance of the weather bet was evident. In a memorandum that accompanied an official report to Eisenhower, Stagg reflected how close they were in the disaster. If the invasion had been postponed to the next appropriate tides, the troops would have faced the worst storm on the channel in 20 years.

“Thank you,” wrote Eisenhower in response. “And thank the war gods we went when we went.”

c.2025 The New York Times Company