Adrián Oyaneder

It was 150 meters long; The system was created to trap vicuñas, a cousin of llamas in some countries.

A team of archaeologists discovered a hunting complex, a trap, which was created ago 6 thousand years in the north of Chile.

A vast system of funnel-shaped traps, used to capture animals such as vicuñas, was discovered in northern Chile thanks to images from satellite.

The complex, which is close to the Camarones River, was built around 6,000 years ago by hunters and shepherds.

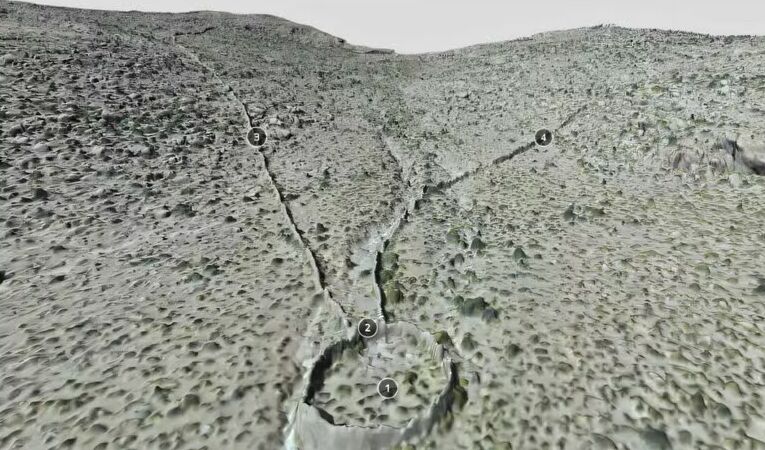

The reveals a system composed of 76 structures called “chacus”, made of stone and organized in ‘V’ shapes, with dry stone walls up to 1.5 meters high and around 150 meters long.

Some traps take advantage of the natural relief of the land, with traps measuring around 95 square meters and two meters deep, sufficient to retain the animals targeted for hunting.

It’s the first time that structures of this type are found in Andes, raising the hypothesis that they were built before the emergence of the Incas, highlights the magazine.

The research also revealed about 800 human settlementsranging from isolated structures of 1 square meter to complexes with up to nine buildings.

These places would have served as home to groups of foragers — communities that lived off hunting and gathering — for centuries.

“The picture that emerges is that of a landscape occupied by diverse human groups from at least 6,000 BC to the 18th century”, explains Adrián Oyaneder, from the University of Exeter, in the United Kingdom.

The discovery challenges the previous view that local populations in northern Chile were already predominantly farmers from 2000 BC, when plant cultivation and animal domestication began to expand.

Colonial historical evidence also mentions foraging groups, known as “uru” or “uro”, reinforcing the continuity of hunting practices in the region.

To map the territory, Oyaneder and his team analyzed 4,600 kilometers squares using satellites, drones and 3D processingcreating digital maps that made it possible to identify the distribution of chacus and settlements.

The study suggests that human groups moved strategically across the highlands, combining hunting, gathering and agropastoral practices in a network of outposts and seasonal sites.

“These discoveries show overlapping ways of life, where vicuña hunting played a central role, coexisting with agricultural and pastoral activities”, highlights Oyaneder. The research expands knowledge about the complexity of pre-Inca societies in the Andes and the importance of hunting in the social and economic organization of these communities.