Over the past three years, Washington has claimed broad power to impose global rules that prohibit companies anywhere in the world from sending cutting-edge computer chips or the tools needed to make them to China. US officials have argued that this approach is necessary to ensure that China does not gain an advantage in the race for advanced artificial intelligence.

But a sweeping set of restrictions announced by Beijing last week showed that two parties can play that game.

The Chinese government demonstrated its own influence over global supply chains by announcing new rules that restrict the flow of critical minerals used in everything from computer chips to cars and missiles.

FREE TOOL

XP simulator

Find out in 1 minute how much your money can yield

The rules, which are expected to come into effect later this year, have shocked foreign governments and companies, who may now need licenses from Beijing to market their products, even outside China.

With its dominance over the production of these rare earth minerals and its control of other strategic industries, China may have an even greater ability than the United States to control supply chains, analysts say.

“The U.S. now has to face the fact that there is an adversary that can threaten substantial parts of the American economy,” said Henry Farrell, a political scientist at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Continues after advertising

The United States and China are now very clearly “at a much more delicate stage of mutual interdependence,” he added.

“China has really started to figure out how to follow the U.S. playbook and, in some sense, play that game better than what the Americans are currently playing,” Farrell said.

Tensions between the two largest economies

China’s move has reignited tensions between the world’s two largest economies, with President Donald Trump threatening to increase already substantial tariffs on Chinese imports by imposing an additional 100% duty on November 1 unless Beijing backtracks on its new restrictions.

The kind of supply chain restrictions China is embarking on first came into play in 2020.

Washington lifted an obscure provision known as the foreign direct product rule out of limbo to target Chinese technology giant Huawei, which the U.S. government considered a threat to national security.

But instead of restricting exports of American technology only to Huawei, the United States said that any company anywhere in the world could not ship a product to Huawei if it contained U.S. parts or was made with U.S. equipment or software.

Continues after advertising

Because of the United States’ key role in the global chipmaking industry, the rules essentially encompassed all advanced technology.

It was a sweeping display of U.S. economic power that became the basis for a series of global technology rules under the Biden administration.

Although foreign governments bristled at being told what to do, many cooperated out of fear of being cut off from U.S. technology.

Continues after advertising

Who will retreat first?

The question now is: Will Chinese restrictions persuade the Trump administration to back off its tariffs or technology restrictions, or will the Chinese government buckle under pressure first?

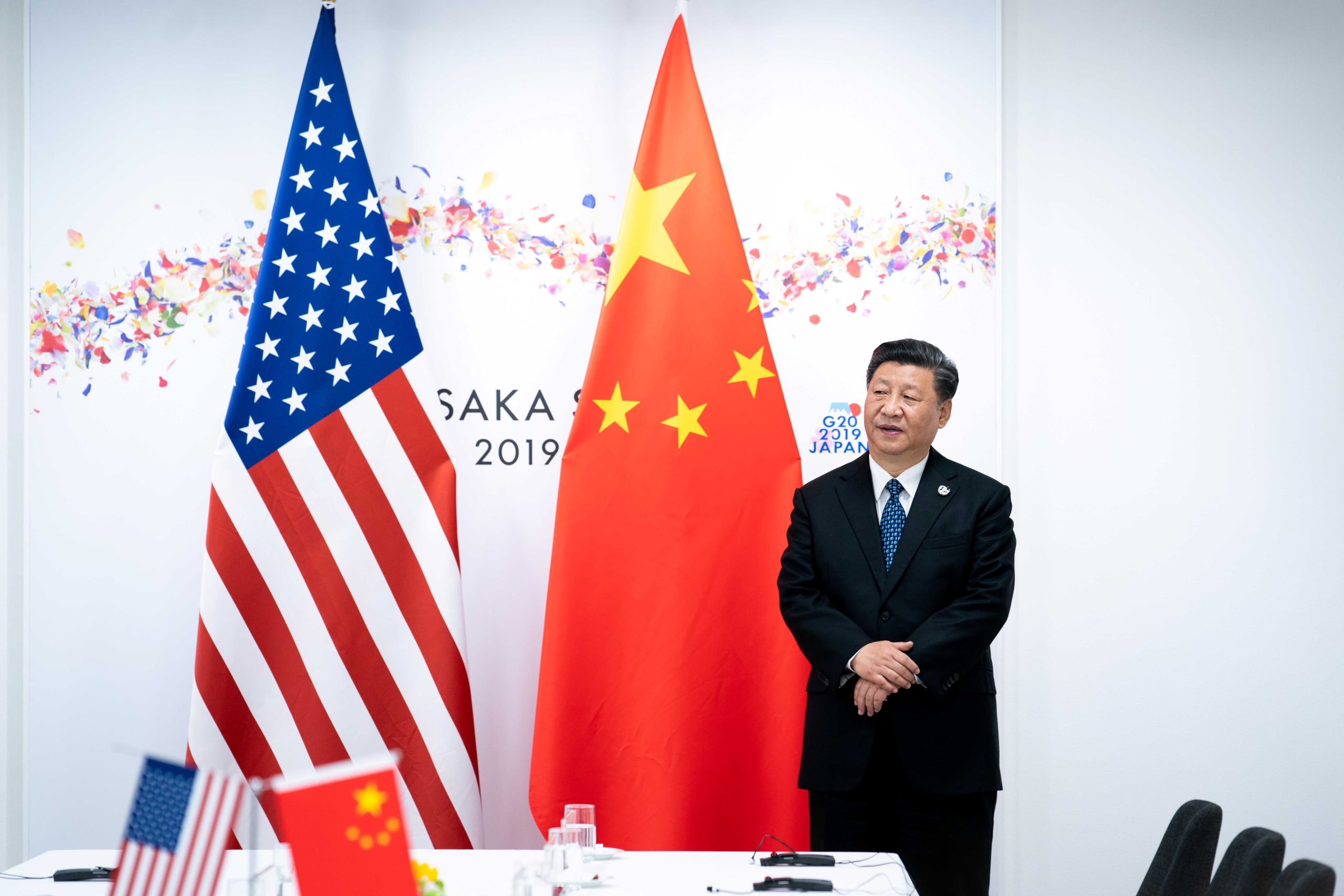

The US government appeared caught off guard by China’s restrictions, which could cripple American industries. Trump threatened to cancel a planned meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, as well as add a 100% tariff.

After stock markets plunged, the president posted on social media: “Don’t worry about China, everything will be fine!”

Continues after advertising

Last week, Trump renewed his criticism, telling a crowd of reporters and the president of Argentina that Xi “gets angry because China likes to take advantage of people and they can’t take advantage of us.”

Trump wrote on social media that the United States was considering ending imports of cooking oil from China, as well as potentially other businesses.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer described the Chinese licensing system as a global power grab and said the United States was ready to impose its tariffs if China moved forward.

Continues after advertising

“Our expectation is that this will never go into effect,” Greer said.

Chinese officials have criticized the extraterritorial application of American economic measures and insist that Beijing has acted consistently in the face of renewed threats from Washington.

“The United States talks about engagement on the one hand, while resorting to threats and intimidation on the other, imposing high tariffs and introducing new restrictive measures,” said Lin Jian, spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry. “This is not the right way to engage with China.”

Jiang Tianjiao, an associate professor at Fudan University, said Chinese officials had noted the United States’ recent efforts to restart its own rare earths industry and that they wanted to demonstrate their strength ahead of a possible meeting between Trump and Xi.

U.S. officials and analysts have said the impacts of the Chinese licensing system would be much broader than U.S. technology controls, which have targeted only more advanced computer chips.

China’s efforts to control supply chains also predate U.S. chip controls, some analysts point out.

Worried about depending on antagonistic nations for oil and technology, the Chinese government has been carrying out plans to build strategic industries for decades. And in 2010, China cut rare earth exports to Japan during a maritime dispute.

It is unclear when Chinese authorities began developing the rare earth licensing system. But Trump’s aggressive actions — including new fees on Chinese-owned ships docking at U.S. ports — have given Beijing the opportunity to experiment with such measures.

“It scares the rest of the world how far China is willing to go to upend the global supply chain,” said Xiaomeng Lu, director of Eurasia Group, a consultancy and policy research group in Washington.

Chris Miller, a professor at Tufts University and author of “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology,” said the implications of China’s new licensing system could be “extraordinarily broad,” affecting almost all semiconductors made globally.

Information about companies is a concern

Companies and governments in the United States, Europe, Japan, India, South Korea and elsewhere are also concerned about the extensive corporate information the Chinese government is requesting in the licensing process.

The United States and China are tinkering with a supply chain that the other has struggled for years to boost domestically.

But while China has spent billions on its chip industry, spurring the growth of its own chipmakers, the United States may need years to restart rare earth production.

“If China can get around chip restrictions but it takes longer for the U.S. to get around rare earth controls, that will be a big problem for Americans,” said Martin Chorzempa, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Yeling Tan, a professor at Oxford University, said events of recent months have placed China in a stronger negotiating position than it held during the first Trump administration.

But she said the controls “could end up being costly for China, in terms of how extraterritorial requirements could alarm other trading partners.”

“This threatens to undermine China’s credibility as a reliable trading nation,” she said. “It’s an incredibly delicate balance to strike.”

c.2025 The New York Times Company