ZAP // Wikipedia

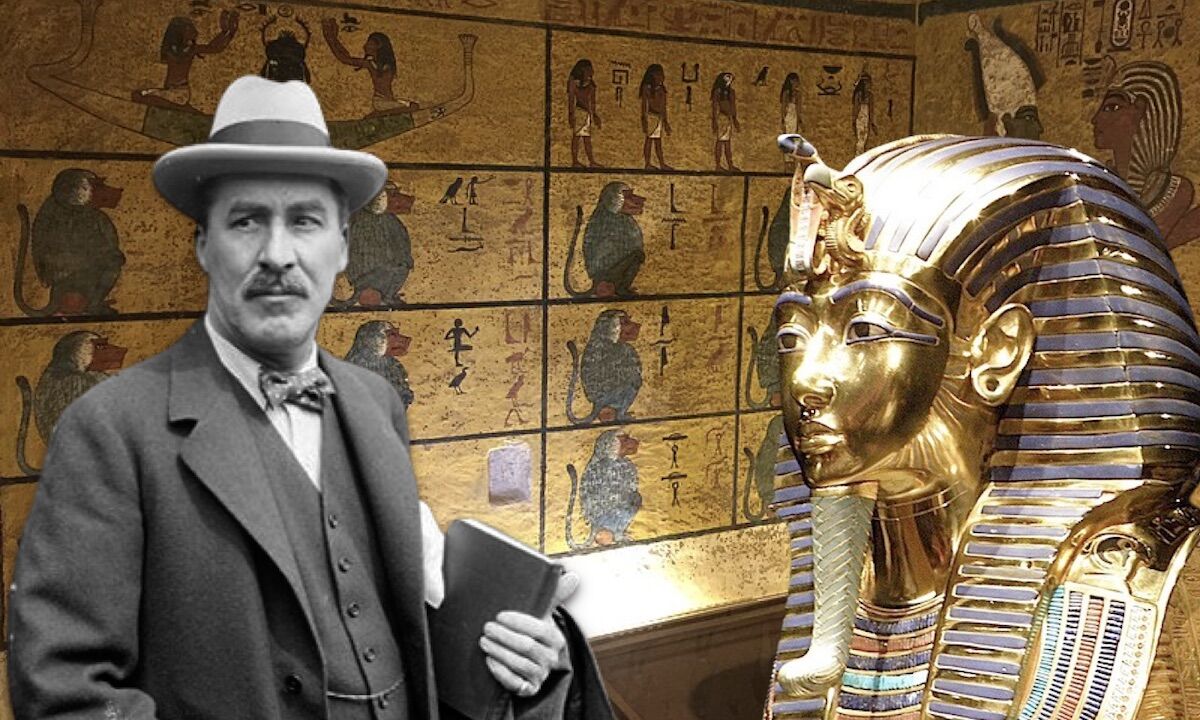

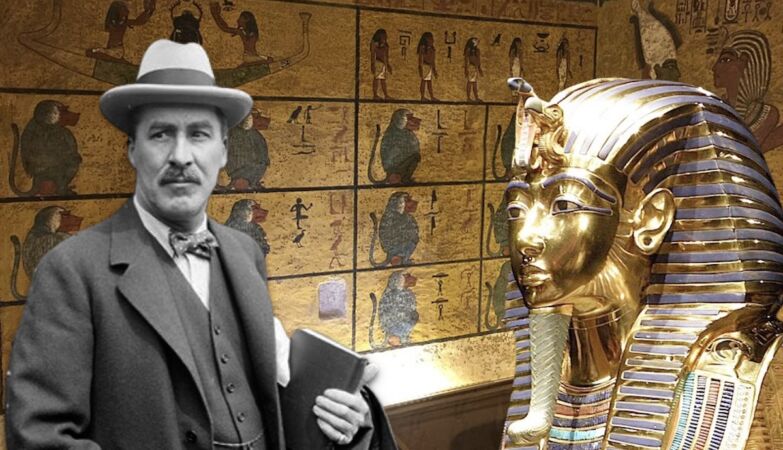

Howard Carter, British archaeologist who discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922

November 2025 marks a century since archaeologists first examined the mummified remains of Tutankhamun. What followed was not a scientific triumph – it was destruction. Howard Carter’s team decapitated the pharaoh and dismembered his torso. Then he tried to hide everything.

2022 marked the centenary of the discovery of the tomb of the mythical King Tuto Pharaoh-Boyso called because he reigned from 10 to 19 years old — a short reign but one that made him the most famous ruler in the history of Egypt.

On November 4th of that year, a member of the team of the infamous British archaeologist Howard Cartertripped over a carved stone, says .

It was the beginning of a flight of buried stairs. In his pocket diary, Carter wrote just five words: “First tomb steps found”.

The discovery took place in Valley of the Kingsand was one of the most important archaeological finds in history. Contrary to what had happened with the tombs discovered until then, which had almost all been looted, the tomb of it was practically intact.

It was necessary several years for workers to clean and catalog the tomb’s antechamber – the first stage of an excavation that would last a decade.

This detailed work, along with delays caused by tensions between Carter and the Egyptian government, meant that only in 1925 Tutankhamun’s remains were finally revealed.

this moment reignited a wave of “Tutmania”, an expression coined to describe the popular fascination with Egyptian archeology following the initial discovery of the tomb.

When Carter’s team opened the innermost sarcophagus, they found the pharaoh’s body. glued to the coffin by a hardened substancea, black, similar to tar, says the historian Eleanor Dobsonprofessor at the University of Birmingham, in an article in .

This resin was poured over the bandages during burial to protect the body from decomposition. Carter described the corpse as “firmly fastened” and noted that “no legitimate force” could release him.

What followed was not a scientific triumph – it was destruction. In a desperate attempt to soften the resin and remove the body, the sarcophagus was exposed to the heat of the sun.

When that failed, Carter’s team resorted to heated knivesbeheading Tutankhamun e separating the funerary mask from the body. Then he tried hide all.

To Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley highlighted that this destruction is notoriously absent from Carter’s public account of the autopsy. Nor does it appear in his private excavation records, kept at the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford and available online.

Tyldesley suggests that Carter’s silence may reflect a deliberate attempt to cover-up or a gesture of respectseeking to preserve the dignity of the deceased king.

The omissions, however, were photographically recorded by archaeologist and photographer Harry Burton. The images constitute a compelling visual testimony of the dismemberment.

In some of Burton’s photographs, Tutankhamun’s skull appears visibly impaled to remain erect during the photo session.

Tutankhamun’s head, photographed by Harry Burton

These images contrast somberly with the photograph chosen by the British archaeologist for the second volume of his work on the excavations, The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amenpublished in 1927.

In this sanitized image, the pharaoh’s head appears wrapped in fabrichiding the severed spine and offering the public a most acceptable version.

As we reflect on the centenary of this examination, it is worth reconsidering the legacy of the Carter-led excavation, not just as a landmark in Egyptology, but as a a moment of ethical assessmentsays Eleanor Dobson.

The mutilation of Tutankhamun’s body, covered up in official reports, forces us to questioning narratives of archaeological triumph and revisiting the past with a more critical eye.

“Today, history in archeology was made,” wrote Carter in the excavation diary on November 11, 1925, when the medical examination of Tutankhamun’s remains began.

But the archival documentation reveals something much more complex, even macabre, behind the seductive shine of gold. What should have been a triumph of science was a disgrace — which it didn’t stop here.

Almost 100 years after the discovery of the tomb of the “Child Pharaoh”, a report was made public letter supporting long-standing suspicions: the grave, found practically intact, was later .