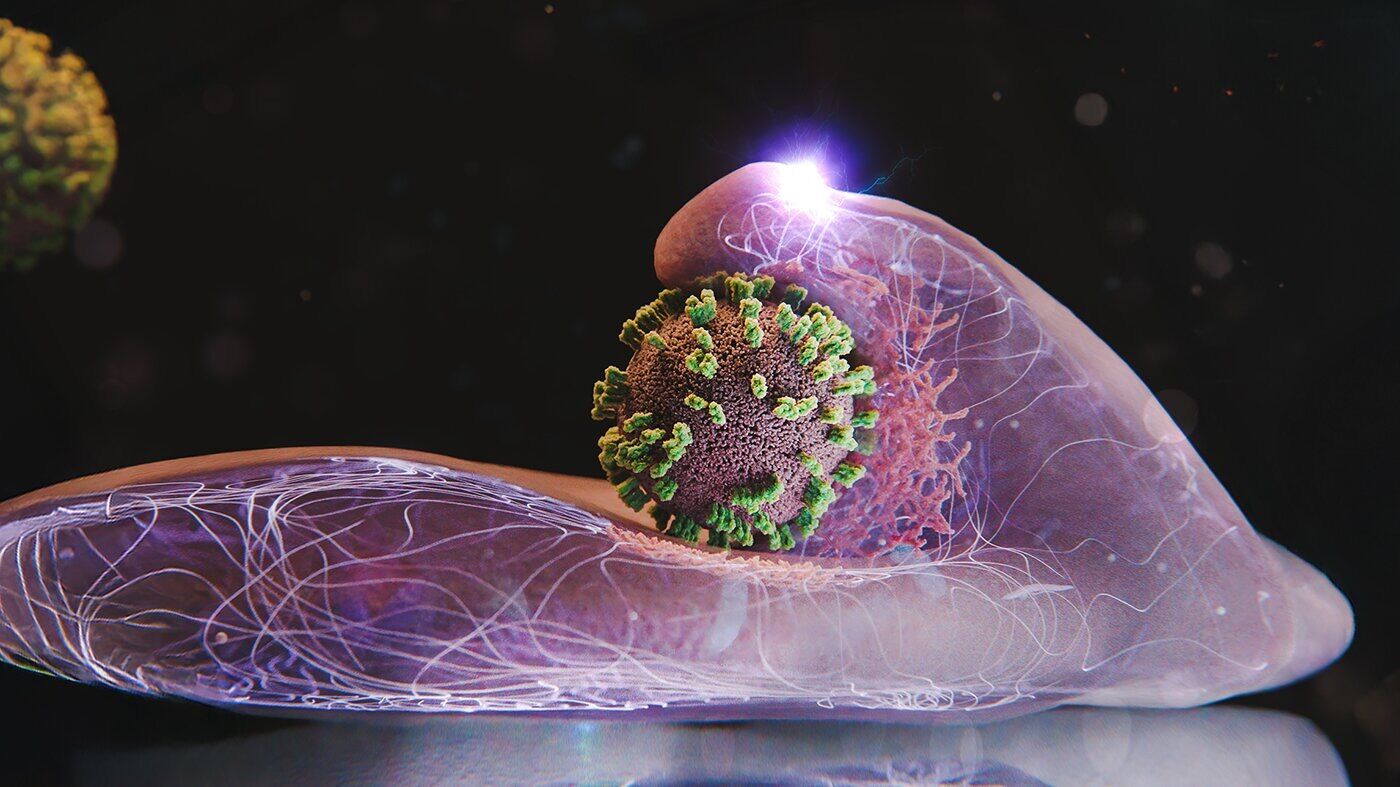

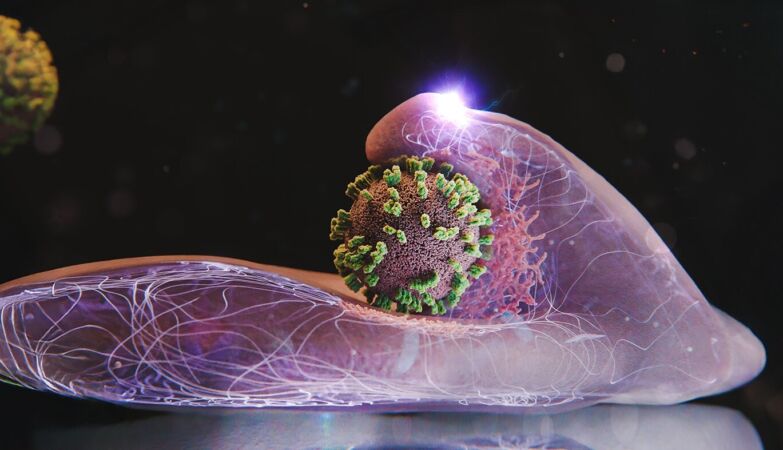

Emma Hyde / ETH Zurich

The cells actively help capture and incorporate flu viruses. In the image, a cell with a virus in the center

The flu is triggered by viruses influenza A and B, which enter the body through droplets and then infect cells. Researchers from Switzerland and Japan have now analyzed the flu virus down to the finest detail.

A team of researchers from ETH Zurich has managed for the first time to see, live and in high resolution, how influenza viruses enter a living cell.

The team, which used a microscopy technique it developed to be able to observe the surface of human cells cultivated in a Petri dish at high magnification, presented its work in a recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Led by Yohei Yamauchi, professor of Molecular Medicine at ETH Zurich, the researchers were especially surprised with one aspect: the cells are not passive: they do not simply let themselves be invaded by the flu virus. On the contrary, actively try to capture it.

“The infection of our cells It’s like a dance between the virus and the cell”, says Yamauchi, quoted by .

Of course our cells gain nothing from a viral infectionnor with the fact that they actively participate in the process. This dynamic interaction happens because viruses appropriate a mechanism of uptake of substances, essential for cells, which serves to introduce vital substances into the cell such as hormones, cholesterol or iron.

Like these substances, also viruses influenza they have to connect molecules present on the cell surface.

This dynamic is similar to “surfing” on the surface of the cell: the virus explores the surface, binding here and there to a moleculeuntil finding an ideal entry point — a place where there are many receptors close to each other, which allows for more efficient uptake into the cell.

When the cell’s receptors detect that a virus has bound to the membrane, a virus forms at that point. depression or “bag”. This depression is shaped and stabilized by a special structural protein known as clathrin.

As the bag grows, it encompasses the virusuntil giving rise to a gallbladder. The cell then transports this vesicle to its interior, where the coating dissolves and release the virus.

Previous studies on this key process have used other microscopy techniques, including electron microscopy. How do these techniques imply destroy cellswere only able to provide snapshots of the process. Another technique also used, fluorescence microscopy, keeps cells intact but offers only limited spatial resolution.

The new technique, which combines atomic force microscopy (AFM) and fluorescence microscopy, is known as virus-view dual confocal and AFM (ViViD-AFM). Thanks to this method, it is now possible to follow in detail the dynamics of the virus entering the cell.

In this way, the researchers were able to show that the cell actively promotes the entry of the virus at several levels. A cell recruits, for example, clathrin proteins, fundamental in this process, to the exact location where the virus is located.

The cell surface also actively captures the virusforming a kind of bulge at this point. These wave-like movements of the membrane become even more intense if the virus moves away from the cell surface again.

The new technique thus provides essential clues for the development of antiviral drugs. For example, it is suitable for testing, in real time, the effectiveness of potential drugs in cell cultures.

The study authors emphasize that this approach could also be used to investigate the behavior of other viruses or even vaccines.