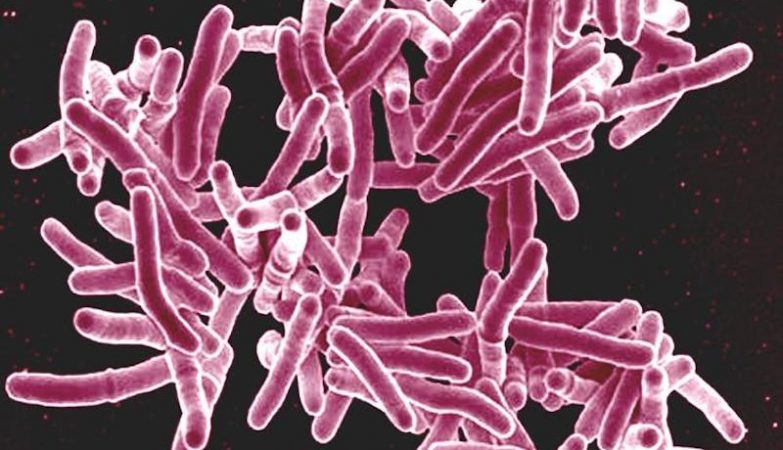

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (tuberculosis bacteria)

A new study deactivated PrrAB in laboratory cultures of M. tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes tuberculosis, and could open the door to the total eradication of the disease.

Scientists discovered the “Achilles heel” from tuberculosis, the infectious disease that kills the most humans worldwide.

A published in the American Chemical Society: Infectious Diseases discovered a molecular vulnerability in Mycobacterium tuberculosisthe bacteria that causes the disease, which could pave the way for a new generation of targeted therapies.

Despite being treatable and curable, tuberculosis (TB) continues to kill more people worldwide every year than any other infectious disease. Once known as “the king’s evil”, TB devastated Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries and continues to be a major global threat.

Now, a study led by Arizona State University infectious disease microbiologist Shelley Haydel has revealed that TB depends on a two-component vital molecular systemknown as PrrAB. This system, he explains, functions as the equivalent of a heart and lungs for the microbe, regulating genes essential for respiration and energy production. When PrrAB is deactivated, the bacteria cannot survive.

Haydel’s team used CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to deactivate PrrAB in laboratory cultures of M. tuberculosis. The result was dramatic: the bacterial population fell almost a hundred times. Although not all related mycobacterial species were affected equally, tuberculosis itself was found to be highly vulnerable.

PrrAB controls key processes including oxidative phosphorylation, the molecular pathway through which cells generate ATP, their main source of energy. Block this regulatory system suffocates the bacteria inside. “The essentiality of the PrrAB two-component system positions it as a promising therapeutic target,” said Haydel, cited by .

The researchers also tested an existing experimental anti-tuberculous compound, Diarylthiazol-48 (DAT-48), which kills tuberculosis bacteria by inhibiting PrrAB. When scientists combined DAT-48 with CRISPRi repression, the bacteria died even more quickly. Even alone, DAT-48 proved to be more potent when combined with existing anti-tuberculous drugs, such as bedaquiline or telacebec, suggesting that the microorganism’s respiratory tract is essential for its susceptibility.

Although neither CRISPR-based therapies nor DAT-48 have been tested in humans, the research points to a potentially innovative approach. If these methods prove effective in living organisms, scientists say that tuberculosis may one day be completely eliminated.