“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in need of a wife.” The opening of “Pride and Prejudice” is often cited as a stylish joke about rich men, but the target is elsewhere. She does not describe male desires; explains what entire families need to accept as truth to continue functioning in a world in which it is, above all, an economic arrangement. Those who “recognize” this truth are mothers with single daughters and relatives worried about inheritance and dowry, for whom a neighbor with four or five thousand a year is not a neutral presence, it is a rare chance in a market that is too narrow.

“Cents and Sensibility”, by Gary Saul Morson and Morton Schapiro, gave its name to what I already intuited after graduating: novels are not decoration for theories, they are another form of evidence about behavior, culture and moral dilemmas. They call this conversation between economics and humanities humanomics, in which models remain important. However, they can benefit when they dialogue with narratives capable of registering shame, pride, loyalty, fear, everything that disappears when the world needs to fit into a few variables.

Austen writes in a society in which few women can work in a socially acceptable way, almost none control wealth, and marriage is the main channel of access to income, housing, and some degree of autonomy. The conflict that runs through his novels is not an abstract dilemma between love and money, but another that serves immediate affection, but weakens the entire family.

Furthermore, families that treat income and savings lightly maintain consumption standards above what they can afford or refuse to plan succession, and end up exposed to poverty, dependence and humiliation; couples who run away “for love”, without a stable income or defined profession, discover that the feeling does not solve rent, debts or social prestige. In an inheritance regime concentrated among a few men, with narrow opportunities for respectable work for women, a decision made in youth can close off almost all alternative remedies later on. At the same time, Austen does not absolve materialism: she is harsh with characters who treat marriage only as a property transaction and forget that they will have to live with the person on the other side of the contract.

Michael Chwe, in “Jane Austen, Game Theorist”, reads the novels as studies in strategic reasoning long before game theory: characters evaluate incentives, anticipate reactions, hide information and decide under power asymmetries that limit their field of action. Darwyyn Deyo argues that Austen clearly works with the “economic way of thinking”, articulating poverty, investment in education, and reputation in a way that speaks to later economic debate. In this light, the author’s insistence on annual income, dowries and inheritances ceases to be a pedantic detail and becomes the implicit design of the space of choices available to each family.

The moral layer fits into the same concern. In “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” Adam Smith describes our tendency to automatically admire the rich and neglect the poor as functional for preserving hierarchies but corrosive to ethical judgment. Austen transforms this tension into scenes and dialogue: figures fascinated by money and title come to see people as stepping stones; others insist on value criteria that do not fully fit into asset accounting and pay dearly for this, whether in social isolation or material insecurity. The conflict is not between a material world and a “pure” world of feelings, but between different ways of harmonizing affection, respect and survival within the same narrow set of opportunities.

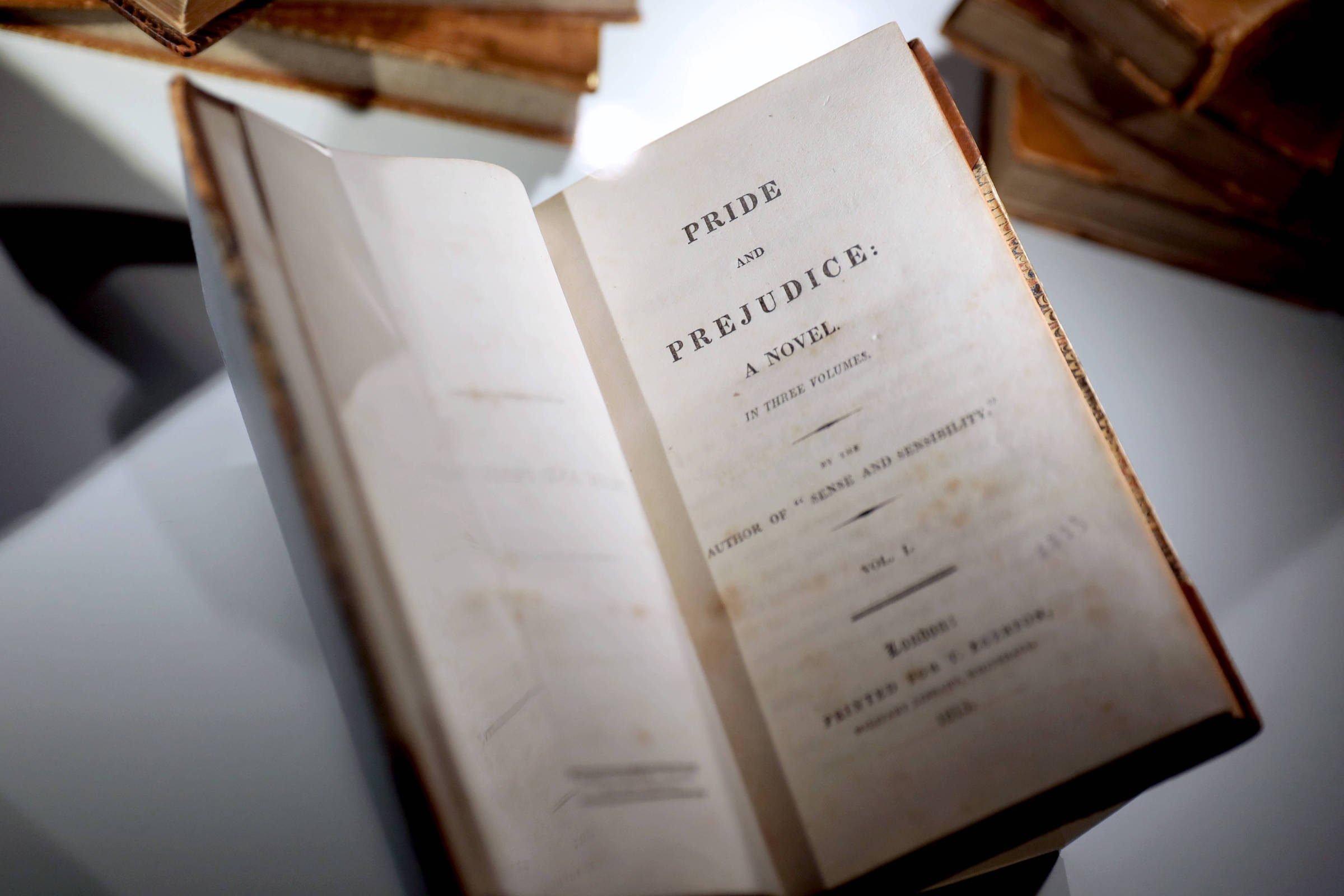

including the return of 2005’s “Pride and Prejudice” to screens and announcements of new adaptations. Anyone who comes to it through the cinema may be looking for sharp dialogues and a happy ending, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But for those interested in income, inequality and restricted choices, it’s worth taking advantage of the opportunity to read or reread the novels from a different perspective. Behind the balls and the English landscapes, Austen continues to ask what we do when money, affection and the future appear compressed into the same decision, and the answer remains uncomfortably current.

LINK PRESENT: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click the blue F below.