It can be, for example, the presentation of identity documents and subsequent verification through a video selfie, face or voice recognition, but also “age estimation”, which analyzes online behavior and interactions in order to estimate a person’s age, informs . Meta and Snapchat started the checks last week when they started deleting the accounts of minors. Teenagers can get back accounts that have been unfairly canceled – even if they present proof of identity or a bank account with a photo.

This is also why critics are worried about what companies will do with so much personal data needed to verify the age of users. However, the Australian government promises that the law also thought of this. Under threat of heavy fines, companies must guarantee that the data will only be used for age verification and will then be destroyed immediately.

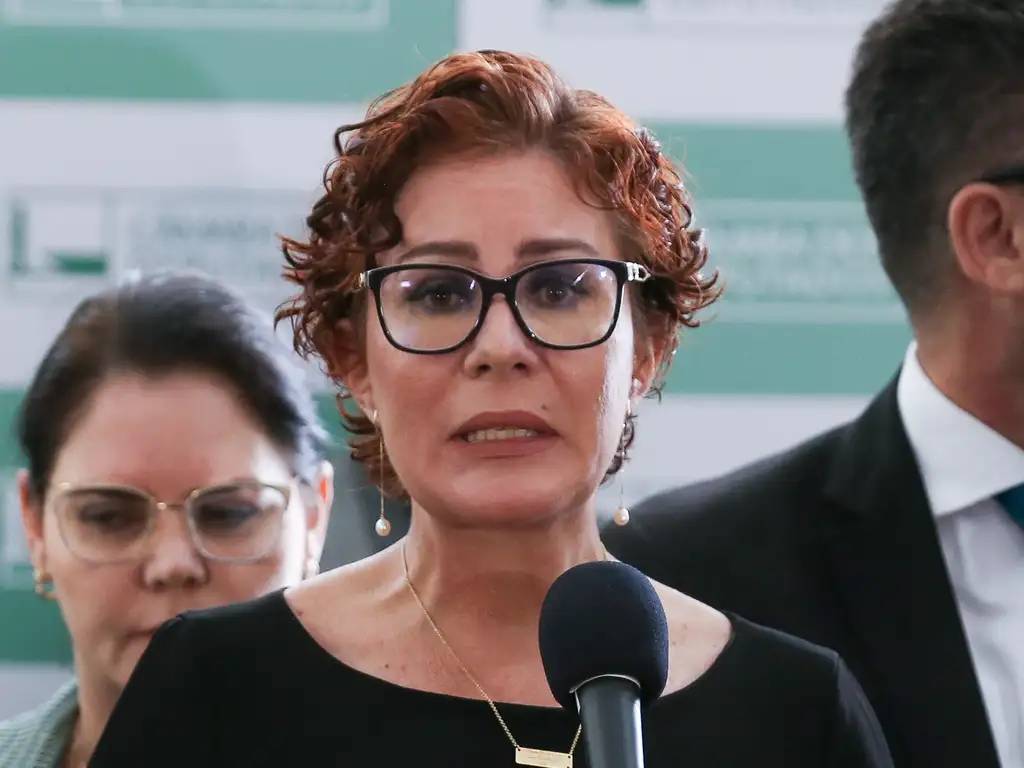

Australian Communications Minister Annika Wells admitted that the ban may not be “perfect”. “It’s going to look a little unkempt during the transition. Big reforms always look that way,” she said.

Europe is already reacting

Under the leadership of the rotating Danish presidency of the EU, whose main goal has been to protect children online, the European Parliament adopted a non-legislative in late November, in which its members expressed deep concern about the threats to which minors are exposed online. The report aims to strengthen protection against manipulative strategies that can lead to addiction and negatively affect children’s ability to focus and interact healthily with digital content.

A key proposal by the EP is to unify the EU-wide minimum age for access to social networks, video-sharing platforms and artificial intelligence companions to 16. Children between the ages of 13 and 16 would only be allowed access with parental consent. In the spirit of personal data protection, Parliament also supported the development of a European application for age verification and a European digital identity (eID).

Unlike Australia, the European report is pressing to address the ethical and legal challenges associated with generative AI tools, particularly regarding deepfakes, social chatbots and nudity-focused AI apps that create manipulated images without people’s consent. As for online games, the deputies request the application of the rules of the Digital Services Act to online video platforms as well. This means, for example, the prohibition of gambling practices such as digital packages (so-called loot boxes).

The Danish rapporteur for this topic, Christel Schaldemose (S&D), called the current vote in the European Parliament a historic moment. “I am proud of this Parliament that together we can protect minors online. Together with strong and consistent enforcement of the Digital Services Act, these measures will dramatically increase the level of protection for children. We are finally setting a line. We are making it clear to platforms: your services are not intended for children. This is where the experiment ends,” she said in the debate.

Children face hate and bullying online

Australia decided on this step also because the data has long been pointing to the harmfulness of social networks for young people. A survey by the Australian Bureau of 2,629 children aged 10 to 15 confirms the shocking extent to which children have been exposed to risks online.

The results show that up to 71 percent of children have encountered harmful content, 57 percent have encountered online hate and 52 percent have been the target of cyberbullying. Up to 25 percent of children have personally experienced online hate, 34 percent have experienced online sexual harassment, and 14 percent have experienced online grooming.

It is not only about social networks, but also communication and game platforms. These data thus pointed to the urgent need for more comprehensive protection of children in the entire digital environment.

The key is moderation, not total prohibition

Another extensive survey from last summer by Mission Australia among more than 17,000 Australian young people between the ages of 15 and 19 shows that the decisive factor in this matter is not a ban, but moderation. In fact, teenagers who spend one to three hours a day on social media show similar or even better mental health outcomes compared to those who use them less.

The survey showed that up to 97 percent of young people use social networks every day, while 53 percent of respondents belong to moderate users (1 to 3 hours a day). Up to 38 percent belong to intensive users (three or more hours a day).

Teenagers with moderate social media use reported better well-being than their counterparts in many aspects. For example, on the question of control over life, 61 percent of moderate users described more control than low users (59 percent) and significantly more than heavy users (51 percent).

This group was also as willing to seek parental help as low users (63 percent), as opposed to heavy users (52 percent). And moderate users also reported less difficulty socializing (26 percent) than low users (28 percent).

The problem is not social networks themselves

According to youth mental health organization Orygen, these results challenge the theory that any social media use is harmful to young people and suggest that “social media alone is not a problem for all young people.”

An interesting point of the survey is the questioning of the opinion that social networks displace young people from physical activities. Indeed, the findings showed that more than half (55 percent) of intensive users of social networks are engaged in sports. For moderate and low users, it is 67 percent.

The report itself recommends that instead of relying only on banning social networks, it is crucial to increase digital literacy among teenagers. Safety should be ensured for all users, regardless of age, the authors emphasize.